Our Cummings Ancestors, Mary Towne Easty

and the Salem Witch Trials

Please remember to view either on a full screen monitor or a laptop.

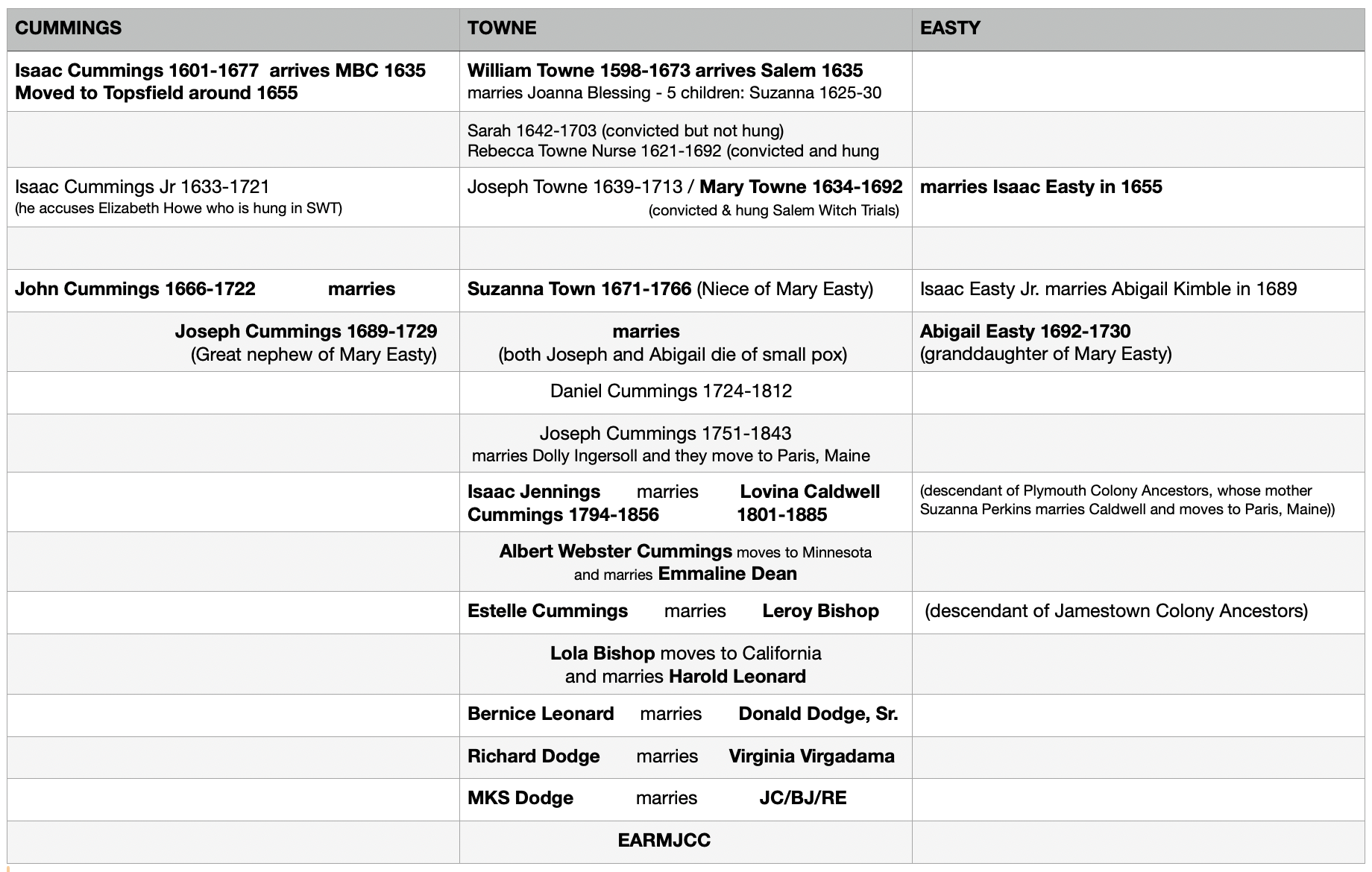

Once again, as a child I carried around the story that I was related to a witch hung in the Salem Witch Trials, which of course meant to my friends that I was a witch too – which was great fun. Then when Mom and I began our research in the mid 1970’s I learned who this “witch” was, why she was hung and how we were related to her. At that time all we knew was that Mary Towne Easty was the “witch” in question, she was targeted as the result of family feuds, battling over land boundaries and that her granddaughter, Abigail Easty, would marry our Cummings ancestor, Joseph, two decades after Mary’s death. It wasn’t an especially close connection – only interesting to know.

But then, as with many of my surprising discoveries through familysearch.org, I learned that there was another earlier marriage between the Towne and Cummings families. Mary Towne Easty’s niece, Suzanna Towne married John Cummings, the grandson of Isaac, our first Cummings ancestor in America.. Even more surprising was that their son – the great nephew of Mary, was also the very Joseph Cummings who would marry Mary’s granddaughter. This meant that their children would be more Towne and Easty than Cummings – very good news for us, for – as you will see – there isn’t much to like from the little we know about Isaac, and even less about his son, Isaac Jr. – grandfather of Joseph.

Moreover, I learned that the Cummings and Towne families both immigrated from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the same year – 1635 – and that both families owned land and were living and working in Topsfield when the nightmare of the Witch Trials began.

Here is a portrait believed to be of Isaac Cummings on the left, who immigrated with family which included his young son Isaac Jr. born in 1633. And pictured on the right is Mary Town Easty born in 1634 only a year old when her parents immigrated.

And below are the fascinating similarities of their timelines.

Isaac Cummings was born in Mistley, Essex, England and was baptized on April 5, 1601, in Easthorpe, Essex, England, the son of John Commin and Amy Greene. Isaac immigrated with his family to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in October 1635, and received a grant of 35 acres in Waterford in “The Great Dividends” land division of 1636.

Records show that Cummings moved to Ipswich in 1638 where he owned two properties, one adjacent to John Winthrop (the founder and first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony). And in 1652 he purchased a 150 acre farm in Topsfield – also adjacent to Winthrop properties.

Isaac Cummings served in the capacity of Constable in Topsfield, was chosen grand juryman in 1675, and was moderator of the Town Meeting in 1676, and was a deacon of the church in Topsfield for many years.

The only known evidence we have of the characters of Isaac Sr and his son, Isaac Jr. are these two notices – the first demonstrating mere pettiness which the second downright cruelty:

Deacon Isaac Cummings Jr. (1633-1721) and his wife Mary testified that Elizabeth Howe had “cursed their horse with oil and brimstone.” Howe was condemned, and executed in July 1692.

Mary Towne Easty was born in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England to William Towne, a farmer and basket weaver, and his wife Joanna Blessing. They were members of the People of God – Puritans opposed to the excesses of the Church of England and so when the Bishop of Canterbury further reformed the Church to resemble the Catholic church Mary’s parents decided to immigrate to MBC, which they did in 1635.

Mary was one year old when they landed in Danvers Port in North Salem. Their first house was an English wigwam where Mary learned to cook, sew, weave, churn butter and milk cows.

They first lived in Salem Village and then in 1651 moved to Topsfield where William Towne purchased property. And in 1655 Mary Towne married Isaac Easty, a farmer and barrel maker from Topsfield. The couple had seven children and came to own one of the largest farms in the Salem Village area.

Mary’s character will be revealed through historical records of the trials. However, it is especially significant to note that she and Isaac Cummings Jr. were contemporaries – born within a year of one another and then, related through the marriage of Mary’s niece to Isaac Jr’s son and then, even more profoundly, through the birth of their son, Joseph – Isaac’s Jr’s grandson and Mary’s great nephew, who was born just three years before the trials. So one can only imagine the turmoil among these families when Suzanna Towne’s father-in-law becomes an accuser the same year that her aunt becomes one of the accused.

The chart below will hopefully clarify these otherwise confusing geneaological connections. It also demonstrates how the blended lines of Cummings, Towne and Easty would later blend first with our Mayflower ancestors and finally with our Jamestown ancestors.

I won’t relate the complex details of the trails which can be easily Googled – this account is one of the best: https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/the-salem-witch-trials. Instead I will focus on Mary’s role in them – especially because of her powerful influence in helping to bring the trials to an end.

But before we move on to the trials themselves it’s worth exploring the psychological atmosphere of Salem in the late 17th century – an atmosphere so fraught with fear, resentment and clashing values that it was ripe for something as devastating as the trials to happen. There is no end of debate among historians over the exact events which kicked off the trials but most everyone agrees that all three of the the following factors, when combined, created the perfect brew for such insanity to occur:

- The continued belief in Satanism and Witchcraft, exacerbated by increasing violence between settlers and indigenous tribes.

- The burgeoning economy of MBC resulting in an ever increasing economic and social divide, causing intense vengeful resentment.

- The rigid remnants of early Puritanism clashing with the growing influence of The Enlightenment.

I’ll begin with the relationship between the growing violence between settlers and native tribes and the belief in Satanism. Despite the efforts of so many well-intentioned colonists to forge ways to live in harmony with the native tribes (whose lands they nonetheless desperately needed) not everyone on either side wanted peace. Treaties often failed through both simple misunderstandings and intentional deceptions. Many colonists viewed the natives as animals who simply needed to be irradicated. And many natives were unwilling to give up their precious lands for any reason. Violence was therefore inevitable.

As more and more colonists arrived and the creators of the earliest treaties began to die off, enmity between natives and settlers only increased until in 1675 the deadliest war ever on American soil – King Philip’s War – broke out. The war was named after Metacom, the son of the Wampanoag tribal Chief, Massasoit, who adopted the name Philip during the peaceful years of his father’s treaty with the first Plymouth colonists in 1621. But with the death of Masasoit in 1662, tensions grew as colonists began brazenly violating more and more agreements in the treaty until Metacom, now chief, renounced the alliance altogether. Violence broke out in all of the northern colonies which resulted in Salem – whose militia was strong enough to keep its population relatively safe – becoming regularly inundated with settlers fleeing less protected communities. And the horror stories they brought with them of murderous heathens, clearly doing the work of the devil, only inflamed the imaginations of a population already at war with one another over financial and legal disputes. It was easy then to blame everything that was wrong on the work of Satan and to target whomever one resented as being his agent.

Even Mary Towne Easty and her sisters, Rebecca and Sarah believed in the power of Satan, but swore in their depositions that they had faithfully resisted him all of their lives. Unfortunately – and inspite of all three of them having impeccable reputations in Salem Towne, their protestations meant little to those in Salem Village, who resented the prosperity the Towne sisters’ families enjoyed.

And this leads us to next motivating factor behind the trials – the economy.

By the end of the 17th century Salem Town had become a thriving commercial centre based initially on its lucrative fur, fishing and lumber trade, and increasingly on its ship building industry – a key component in the triangle of exchange between England, Africa and the southern colonies, hungry for slave labour.

But Salem Town had one major deficit – no decent soil for growing much needed food stuffs. While neighbouring Salem Village, the centre of its surrounding farmlands did. And because Salem Town was therefore dependent on produce from Salem Village, they used their wealth and consequent influence in MBC’s central government in Boston to keep Salem Villagers from establishing their own town charter, with their own court to manage disputes, their own church and their own militia. For years farming families in Salem Village were forced to travel the 10 miles each Sunday to attend church – which was required to maintain membership, and the men were forced to participate in the Salem Towne militia instead of being able to form their own. And caught in the middle of these disputes was Topsfield where the families of the Towne sisters lived. For reasons unclear – to me, at least – Topsfield had stronger financial and political ties to Salem Town. So when land disputes arose between farmers in Topsfield and Salem Village, they were settled more often than not in favour of the Topsfield farmers.

And the most disgruntled of the Salem Village families were Thomas and Ann Putnam who claimed that some of their land extended into the town of Topsfield – though they were never able to come up with a deed of proof. Nonetheless they accused more victims of the trials than any other family. Thomas signed 10 of the 21 formal complaints against accused witches and their 12 year old daughter Ann was the ring leader of the accusing girls. And when the trials began Thomas sat on the jury.

AND NOW FOR A VERY PERSONAL QUANDRY AND FAR-FETCHED THEORY ABOUT OUR FIRST CUMMINGS ANCESTORS

How could it be that the equally wealthy Isaac Cummings, Jr. was capable of coming down on the side of Salem Village accusers, when his own young grandson was the great nephew of all three Towne sisters? It doesn’t seem to have been a question of financial resentment – like the Putnams. So I looked up the story of the woman he had accused, Elizabeth Howe, hoping for clues and here’s what I found – excepted from the following article in the Historic Ipswich website.

https://historicipswich.net/2023/10/30/the-witchcraft-trial-of-elizabeth-howe/

First I’ll share Howe’s story and then Cummings involvement. The Howe family had had a long-standing war with the Pearly family from years before when the Pearly’s accused Elizabeth of causing – through witchcraft – the illness and death of a child who was actually the niece of both families. So when the trials began the Pearly’s used the hysteria to reignite their accusations against Elizabeth – this, despite the fact that Elizabeth had long been far too busy to be casting spells on anyone as she had to manage both her household and her farm when her husband became blind many years before. It’s been suggested that Elizabeth was so good at handling matters which were normally only handled by men, that there was an overall effort in the community to find ways to bring her down. And one such way had been to deny her membership in the Ipswich church.

Here is the accusation the Pearly’s now made – so similar to the accusation made by Cummings (and as equally absurd) that for pure amusement sake it deserves sharing: In testimony, Samuel Perley stated that a few days after he had first denied Elizabeth’s request to join the church, his cow suddenly went mad and ran into a pond drowning herself. Timothy and Deborah Pearly said their cows would no longer give milk. And Samuel Perley’s son-in-law Jacob Foster testified that he found his mare leaning against a tree and that no matter how much he whipped her she would not move.

And here is an extended version of the Cummings accusation against Howe – introduced earlier: Isaac Cummings, senior, gave testimony that eight years before, James Howe had asked his son Isaac to borrow a horse, which was refused, and that the next day his mare fell down dead. The younger Isaac confirmed the story. His wife testified that Elizabeth had cursed the horse with oil and brimstone. Thomas Andrews testified that he had been called to assist with the mare and had set a pipe of tobacco “under her firmament” to treat the pain and that a blue flame had shot out and set the mare’s hair on fire. They tried this old prescription three times with the same results each time and decided they would rather lose the mare than the barn.

YOU CAN’T MAKE THIS UP ! ! ! ! !

Anyway, because of this nonsense, Elizabeth was arrested on May 28, 1692 and hanged in Salem on July 19, 1692 –

the same day as Rebecca Nurse, Mary’s sister.

Once again, how both of these Cummings could have participated in any of this madness is beyond me: First Isaac Sr’s pettiness in suing a neighbor whose pigs ate his corn, and then both their cruelty in wanting to see die a hardworking woman – caring alone for a farm and a blind husband – whose last possible concern would have been the casting of spells on cows and horses.

And here’s my theory: I noticed that in all the records regarding these two Cummings there is never any mention of a wife for Isaac Sr., nor a mother or even-step-mother for Isaac Jr. and his younger brother John. So I have decided that Isaac Cummings Sr. had to have been a cruel spirited man who either drove his wife away or drove her to her death, after which no other woman would have anything to do with him. And so Isaac’s sons grew up motherless, under the strict discipline of a father, chosen to be town constable, and therefore inherited – at least Isaac Jr. did – his father’s cruel spirit.. But, of course, I have no idea. Maybe Mom knows…

This panel to the left is from the marvellous Ipswich Riverwalk mural by artist and writer Alan Pearsall, depicting Elizabeth Howe being arrested on charges of witchcraft.

Back to Mary. She was arrested on April 21, just a few weeks after her two sisters. She was examined on the 22nd, and imprisoned after denying her guilt. During her examination, Magistrate John Hathorne aggressively questioned Easty, trying to lead her to a confession:

“How can you say you know nothing when you see these tormented [girls], & accuse you that you know nothing?”

“Would you have me accuse myself?”

“Yes if you be guilty.”

“Sir, I never complied but prayed against [the devil] all my dayes… I will say it, if it was my last time, I am clear of this sin.”

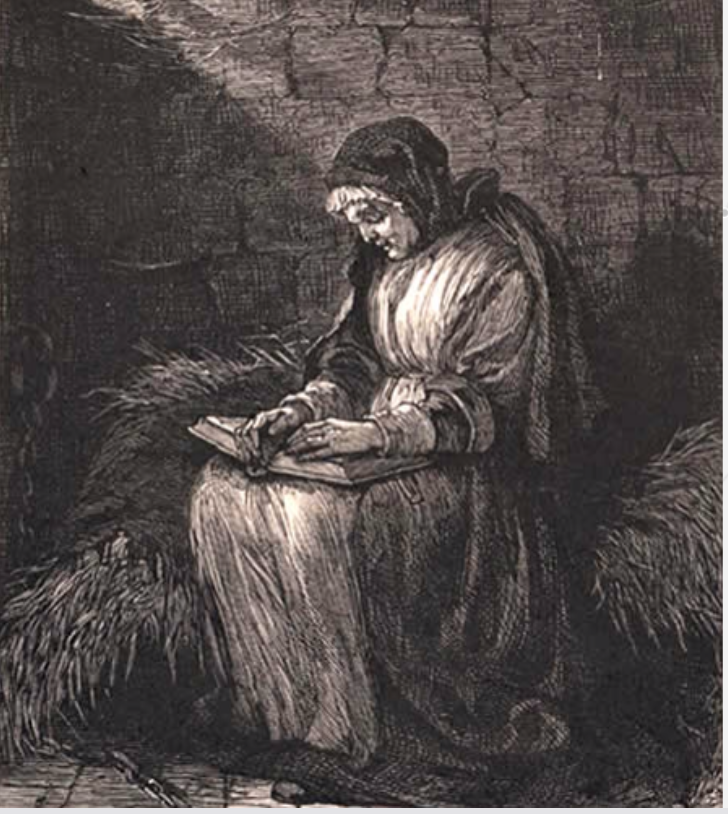

This image of Mary awaiting trial in a cold dark cell, “bound with cords and irons” accurately depicts recorded descriptions. In Marion L. Starkey’s The Devil in Massachusetts he writes, “They were periodically subjected to inspections by prison officials, especially by the juries assigned to search them for witch marks.”

Hathorne, clearly affected by Mary’s responses and demeanour, pressured the girls to reconsider their accusations. They backed off briefly and Hathorne released Mary only to arrest her again when the girls and even several adults insisted once again that Mary was indeed torturing them.

It also did not help her case that years before Mary’s mother, Joanna, had been accused of witchcraft. And though nothing had come of it, this detail was not lost on the court and was used as further evidence against her, since witchcraft had always been considered an inheritable trait.

In a superb analysis of Mary’s influence on the court, Anne Waite Austin wrote the following in her paper: “The Salem Witch Trials in History and Literature”:

“While Easty remained in jail awaiting her September 9 trial, she and her sister, Sarah Cloyce, composed a petition to the magistrates in which they asked, in essence, for a fair trial. They complained that they were “neither able to plead our owne cause, nor is councell allowed.” They suggested that the judges ought to serve as their counsel and that they be allowed persons to testify on their behalf. Easty hoped her good reputation in Topsfield and the words of her minister might aid her case in Salem, a town of strangers. Lastly, the sisters asked that the testimony of accusers and other “witches” be dismissed considering it was predominantly spectral evidence that lacked legality. (Salem Witchcraft Papers, I: 303) The sisters hoped that the judges would be forced to weigh solid character testimony against ambiguous spectral evidence.”

The petition did not change the outcome of Easty’s trial, for she was condemned nonetheless to hang. When their petition failed and Mary was sentenced to death, she submitted a second petition with a plea – not this time for herself but for others – that no more blood be shed by innocent people for simply refusing to deny their faith.

Austin concludes: Easty’s “… case gave insight into the workings of the trials and her eloquent and legally astute petitions have been said to help bring the trials to an end.”

Mary was among the last group of women to be hanged. And while her petitions certainly influenced the court the trials only finally came to an end when the Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, William Phips, who had established the court which tried the witches, and who had tolerated the executions, ordered the court shut down, when his wife was accused. Among those awaiting execution, who were now released, was Sarah, Mary’s younger sister.

This brings us to our last motivating factor behind the trials:

The rigid remnants of early Puritanism clashing with the growing influence of The Englightenment.

And no distinction can be made more evident than two popular books of the time: Cotton Mather’s Wonder’s of the Invisible World 1693 and Robert Calef’s More Wonders of the Invisible World. Cotton, a Harvard educated and highly influential Puritan clergyman wrote his text in 1693 defending the trials, while Calef, a simple but highly literate cloth merchant wrote his ironic response denouncing Mather’s text and his unconsciounable role in defending the trials.

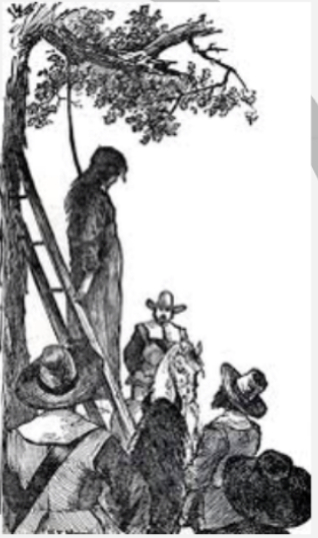

Calef was present for Mary’s hanging at Gallow’s Hill – a horrific event in which each victim was forced to climb a ladder blind-folded, with a noose around her neck – and then wait for the ladder to be pulled away. He sorrowfully wrote: “when she took her last farewell of her husband, children and friends, it was, as serious, religious, distinct, and affectionate as could well be expressed, drawing tears from the eyes of almost all present.”

But I cannot leave you with such a final image so instead I’ve chosen the image, below depicting what a rural farm in the late 17th century might have looked like. It’s clearly idealised, but beautiful nonetheless, nicked from a visually stunning and fascinating tutorial on the Salem Witch Trials.

https://ghostcitytours.com/salem/salem-witch-trials/

I like to imagine Mary Easty’s granddaughter, Abigail – born the year of Mary’s death – and her great nephew Joseph Cummings – born three years earlier – living happily together in a place like this for the remainder of their short lives.

Tragically both Abigail and Joseph died from smallpox before they were 40. But they left behind several children and grand children. And two of them – first their son Daniel and then their grandson Joseph, would go on to live long and fruitful lives. And it was Joseph who would move to Paris, Maine where his son Isaac Jennings Cummings, would meet and marry Lovina Caldwell, the very woman who connects us to our Mayflower ancestors.

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Your comments are welcome. Please contact me at [email protected]