Our Salem and Plymouth Ancestors Meet in Maine

We are finally approaching the stories of our great great grandparents, Albert Webster Cummings, born 1829 in Minot, Maine, and Emmaline Elizabeth Dean, born 1821 in Coburg, Canada. These stories were meant to be the very first stories in “Our Family Stories” because, from the time Mom and I began our research, Albert and Emma were the oldest known ancestors for whom we had enough details for a story to emerge. Anyone who came before was, more often than not, only a name and a date. And the only earlier stories we knew of were our distant relationship to Mary Towne Easty – one of the victims of the Salem Witch Trials, and an equally distant connection to a minor Revolutionary War hero, Col. Josiah Smith.

So when I recently took up this research I never expected to know anything more until, that is, I stumbled upon familytree.org and was delightfully dumbfounded to discover so much more. My research didn’t reveal anything more about Emmaline (so thankfully we have her daughter Estelle’s letters to help us there) but as you’ve seen from my pages about the Salem Witch Trials and the Mayflower, we now know that Albert’s ancestry includes, through his father, the Cummings family’s complex ties to the Towne family and consequently to the Trials themselves, AND, through his mother, our mind-blowing connections to 12 of the Mayflower passengers. And then, remarkably these two stories come together in Maine, where Albert was born, and which up until recently would have gotten no further mention other than “that is where he was born”. But now that we know how these two extraordinary lines come together in four small towns in Maine in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, well, these stories are just too good NOT to be told, and so I give you

THE STORY OF MAINE

Maine had never registered for me as being significant to our family stories. It was merely the birthplace of Albert Webster Cummings, who left his rural community as a young man. Because he was both physically and psychologically unsuited to farm life, he focused first on medicine and then on the ministry – careers he would pursue throughout his life in Minnesota. And so that’s what Mom and I focused on as well. But through more recent research I’ve discovered that Maine is every bit as significant to our Family Stories as Salem and Plymouth, not only because their stories converge there, but because of the significance of Maine in U.S. history.

Maine did not become a state until 1820 – more than fifty years after our first Cummings ancestors moved there sometime in the mid 1760’s. And these ancestors were among some of the earliest colonial settlers in Maine. For many reasons British settlement had been sparse in this northern territory. Between its brutal climate and densely wooded terrain it held even more daunting hardships for settlers than those faced by early settlers to Massachusetts. Moreover the French had powerful interests in this territory and had the wisdom and good sense to become powerful allies of indigenous tribes – focusing on the fur and coastal fishing trades, and sensibly leaving the interior hunting grounds of natives tribes relatively untouched – a wisdom sadly missing among most British colonists.

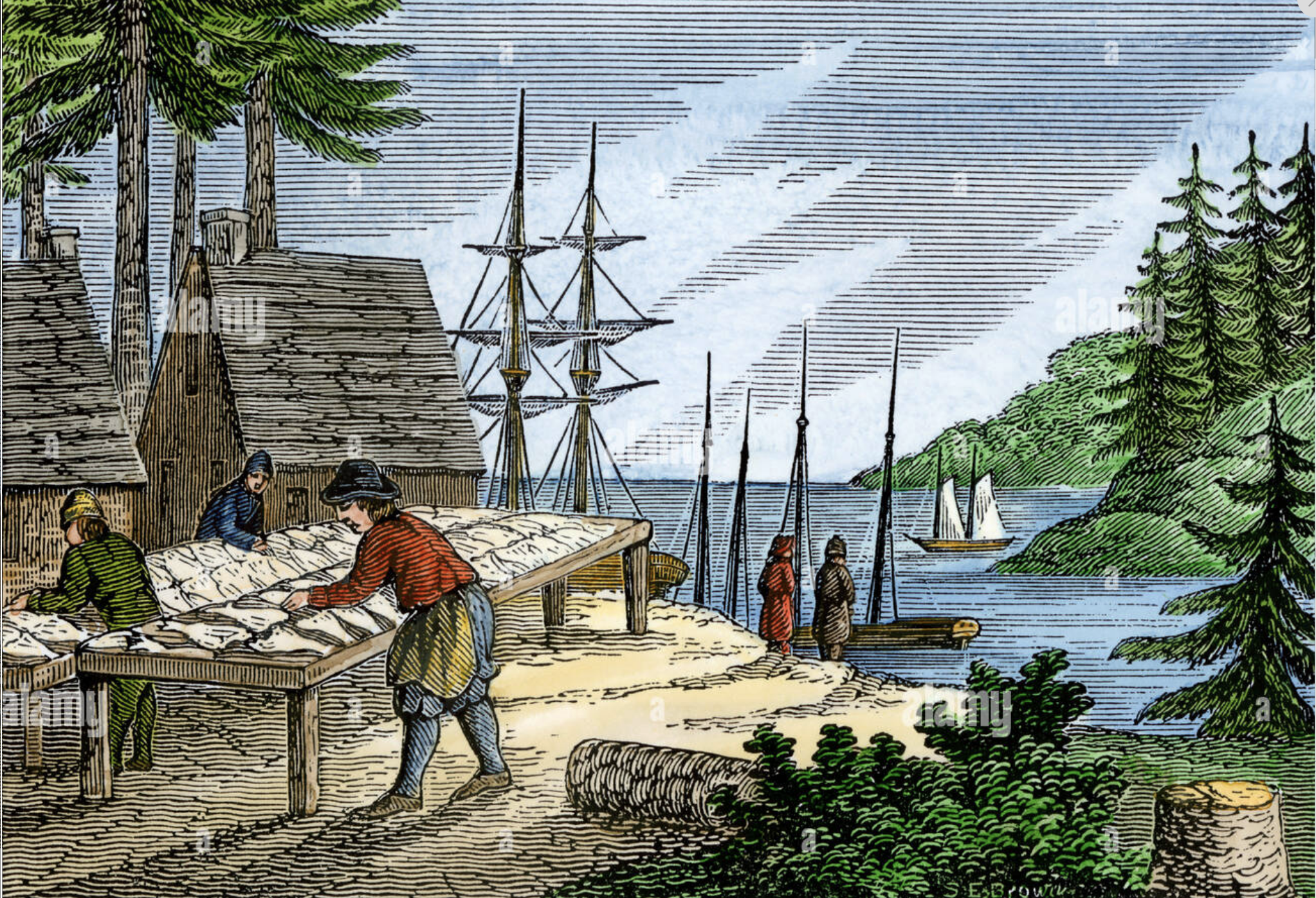

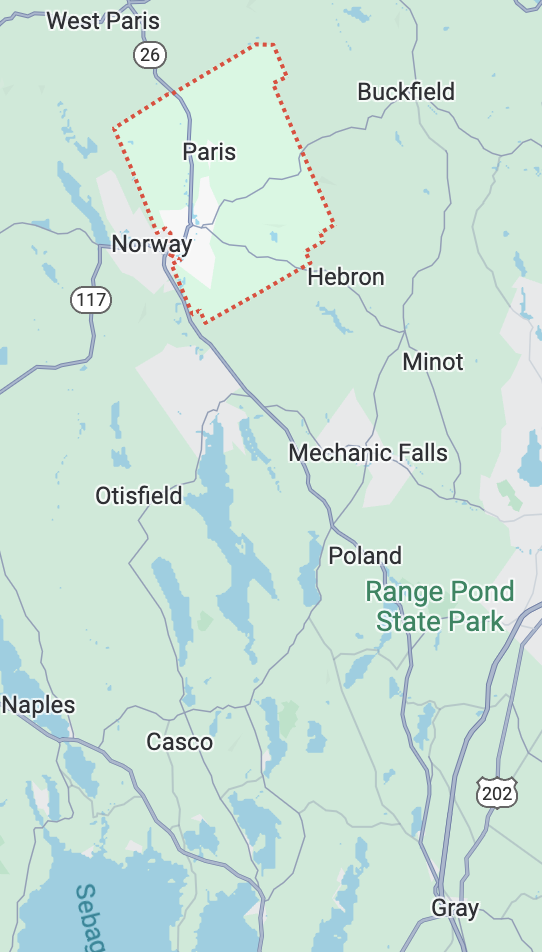

However as the populations of the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies exploded, an increasing need for farmland drove colonists into the interior stripping away large swaths of native forest lands, both for farming and to sell the timber. Plymouth had long been profiting from their fur trade and fishing industries in Maine – with little pushback from native tribes, who benefited from the former and tolerated the latter. And so – for a good many relatively peaceful years – both of these pursuits in Maine enabled the Plymouth as well as the Massachusetts Bay Colonies to pay off huge debts they owed to their investors for their initial passage to America and the establishments of the earliest settlements.

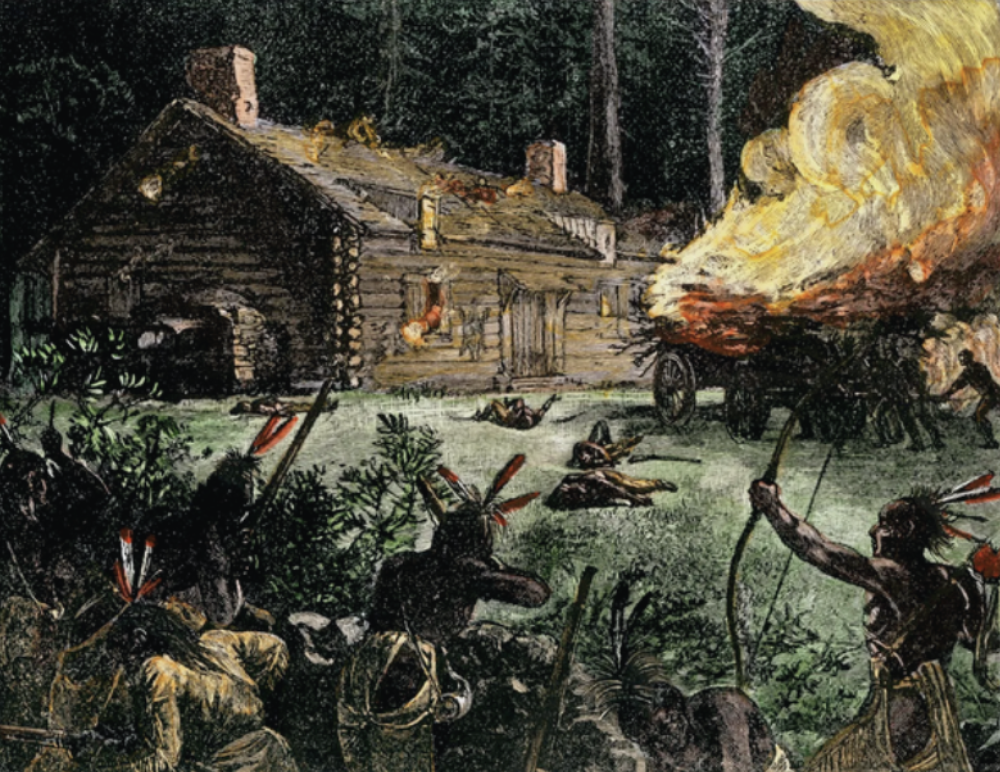

But when colonists began to settle the interior, pushback – aided by the French – was fierce and deadly. King Phillip’s War in the late 17th century impacted all of the northern colonies but was so brutal in Maine that hundreds of traumatised British settlers fled into and overwhelmed Massachusetts towns, which in many ways set the stage psychologically for the Salem Witch Trials.

Intermittent warfare continued throughout the colonies for most of the following century. And only at the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763 – were the British able to drive enough of the last surviving indigenous peoples AND the French out of Maine – making it habitable again for British colonists. And to encourage settlement, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who then had jurisdiction over the Maine territory, offered colonists free land to do so. And this is when our first known Cummings ancestors moved from Topsfield to the small town of Gray in Southern Maine.

Another significant impact on the development of Maine was the Revolutionary War. In the late 1780’s soldiers, who’d been promised land in Maine in exchange for fighting, began flooding into the territory – only to find that the new government had sold off vast quantities of some of the very lands which the soldiers were settling on, to speculators in order to pay their war debts. And these speculators wanted to be paid.

I cannot find concrete evidence that any of our ancestors, who moved to Maine, served in the war and were thus entitled to land. Nor can I find any evidence of the struggles that ensued between settling soldiers and the new proprietors. So my guess is that either they had the means to purchase their properties or that they settled lands that were free for the taking without any ownership issues.

All I know for certain is that several of our ancestors from both the Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colonies settled in four small towns in Southern Maine – between the mid 18th and mid 19th century and it is to their stories we will now turn.

Our Ancestors Begin Settling in Maine

We’ll begin these stories with the town of Gray where the earliest Cummings ancestors migrated sometime before 1766. Then we’ll shift to Hebron, where our first Plymouth ancestors settled. We’ll then travel to Paris where our Plymouth and Salem lineages came together in the 1819 marriage of Isaac Jennings Cummings and Lovina Caldwell, one year before Maine became a state. And finally we’ll travel to Minot where most of their children were born, and most significantly – our great great grandfather, Albert Webster Cummings – in 1829.

Along the way we’ll include the mysterious entrance and impact of Albert’s paternal grandmother – Dolly Ingersoll –

and the Pan European lineage of his maternal grandfather – Phillip Caldwell.

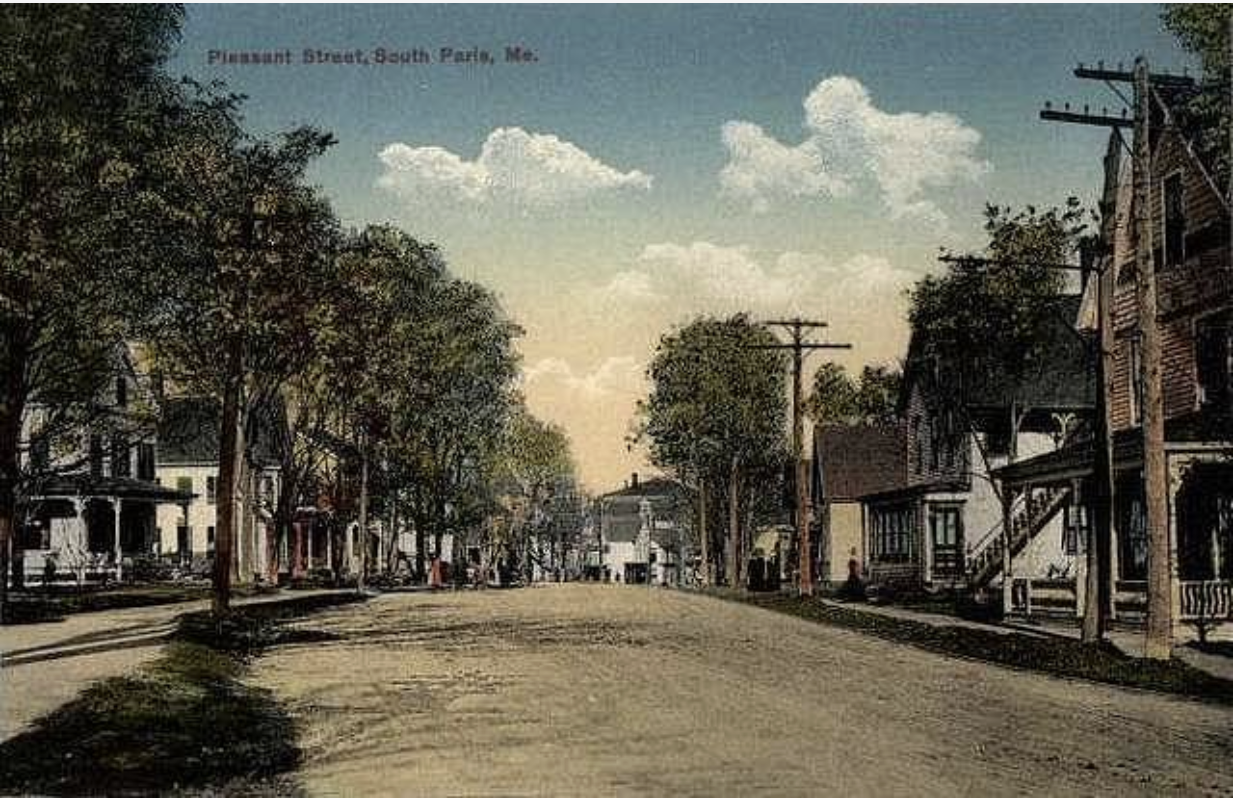

Here below you can visualise where in Maine the four towns are situated and where they still exist today –

calling me to visit them in person – which I hope to do soon.

Gray (bottom right), and Paris, Hebron, and Minot (top centre).

GRAY, MAINE

Where the first Cummings settled after leaving Topsfield.

This antique postcard of Gray, Maine – with faint images of electricity poles in the background – would not have represented the town

when our first ancestors moved there. But I imagine that it did by the early to mid 19th century,

when records show half of Isaac and Lovina’s children being born there.

But first here’s a quick recap from our Salem story which follows the last of our

Cummings ancestors in Topsfield, Massachusetts, before they settled in Gray:

We left Topsfield with the sad story of Joseph Cummings and his wife Abigail Easty dying before the age of 40 from smallpox. Remember that Abigail was the granddaughter (and Joseph – the great nephew) of Mary Towne Easty – one of the last victims of the Salem Witch Trails. Dying within days of each other they left behind five orphaned children between the ages of 4 and 17. And our ancestor was their 4th child, Daniel – only six when they died.

Tragic as it was to loose their parents so young, these children were nonetheless blessed to have a cadre of aunts and uncles to care for them. For, not uncommonly, two of Abigail’s sisters were married to Cummings men – one to Joseph’s brother and the other to his cousin. Daniel would most certainly have grown up in one of these families before he married Mary Williams, a widow with two children. (Mary, was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts – a point that will be significant later in our story.) Daniel and Mary would go on to have 13 more children and their third child, born in 1751, was our next ancestor, Joseph, named for his grandfather.

Daniel and Mary Cummings Move from Topsfield, Massachusetts to Gray, Maine

We don’t know exactly when Daniel and Mary moved from Topsfield to Gray, Maine, only that it was probably not long after the birth of their last child, Daniel Jr, born in 1766 in Gray.*

* Recent discovery: Another search site identified this last child as “David”, not Daniel Jr. It may be more accurate for it identified David as the first male child to be born in Gray and that his descendants are living there still. This new and contradictory information came with an antique hand-drawn map of Gray showing the exact location of Daniel and Mary’s farm. AND yet another site indicates that neither Daniel nor David was their last child. There is evidence of another son, Amos, born in 1768 and another daughter, Sarah, born in 1770 – both in Gray. Their mother Mary’s death is listed as in Gray, but with date unknown. So my work is cut out for me when I visit New England this coming Fall. You can see this extraordinary map of Gray in Dolly’s Story on the next page.

But we do know that Daniel and Mary brought with them seven of their surviving children and that all of these children would grow to adulthood, marry, have many children and then die, either in or close to Gray. And while we have no birth or death details for the five children who did not survive infancy, nor a specific day for Mary’s death, we can presume that she died no later than 1770 and most probably in childbirth. After her death Daniel married Lucy Knowlton, 21 years his junior, but there is no evidence of more children or of when and where she died. We only know that Daniel lived well into the next century, dying at age 88 in Gray.

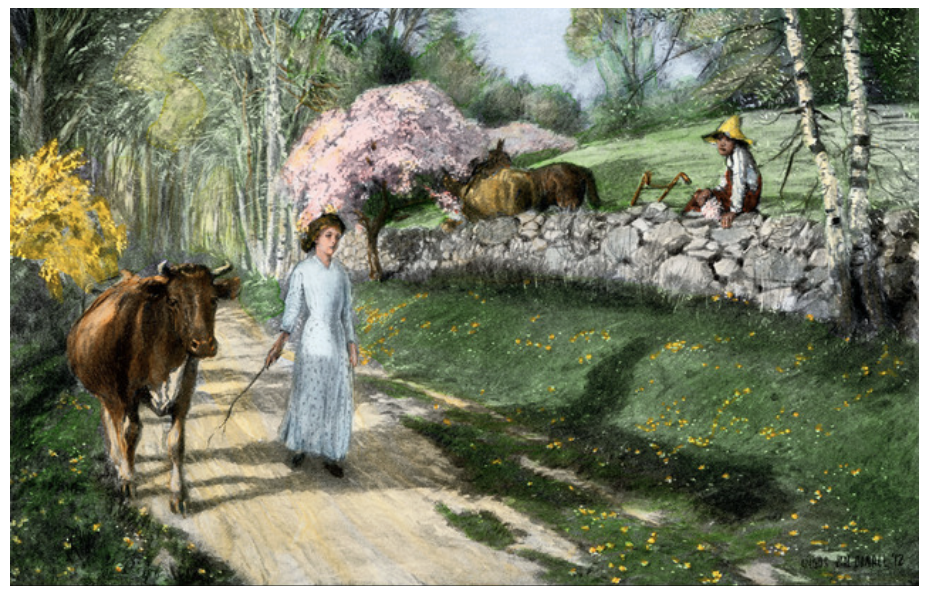

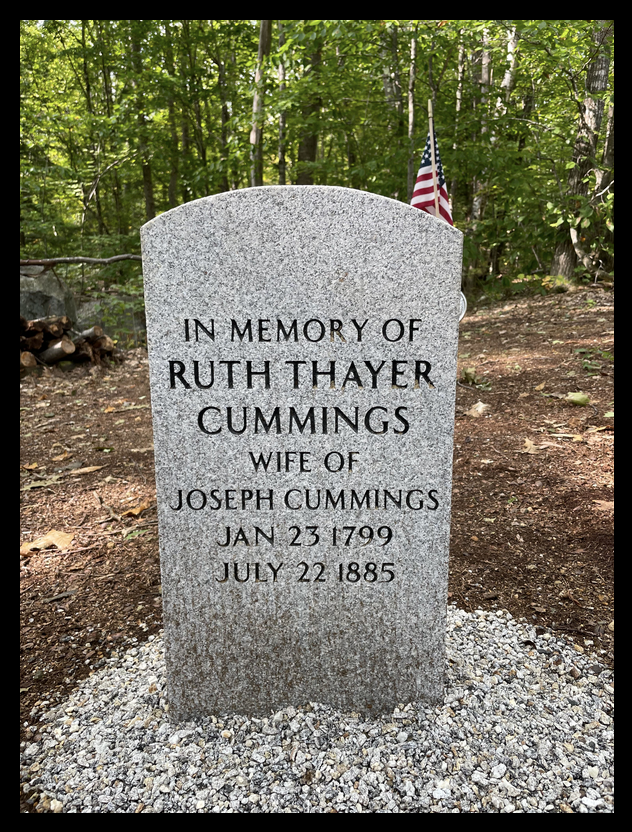

With so many Cummings siblings settling and raising large families in Gray, I like to imagine their world resembling something like the woodcut below, depicting 18th century New England farm life. But even if it is an overly idealised depiction, you, my patient readers deserve it as a lovely visual interlude from so many names and dates.

Lovely visual interlude over and time to move on to Daniel and Mary’s third child, our ancestor, Joseph.

Joseph was no more than 15 when his family moved to Gray and somewhere between 17 and 20 when his mother died. Then when Joseph was 24 he married Margaret Sanger and they had four children – one who died in infancy followed by three more: Lucy in 1778, William in 1780 and Benjamin in 1781. Then only one year later, in 1782, Margaret died, leaving Joseph with three young children to raise on his own.

The ENTRANCE of DOLLY INGERSOLL and her UNFATHOMABLE STORY

It was common for colonial widows and widowers to marry again quickly, but Joseph would not marry again. Perhaps with the support of his older sisters and young step mother, Lucy, he did not feel the need. Nonetheless several years after Margaret’s death, another woman would come into his life. And with her he would have two more sons – Joseph Jr, born in 1791, and our ancestor, Isaac Jennings, born in 1794. That woman was Dolly Ingersoll.

Dolly was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1755 and died in Newburyport, MA in 1816. (Remember that Joseph’s mother, Mary, was also born in Gloucester – which might hold significance in their story.) She and Joseph were both in their late 30’s when they had Joe Jr and Isaac, so I wondered if Dolly had been married before, and sure enough she was – only not before. She was married to a Newburyport man by the name of Enoch Greenfield and had 4 children with him over the same six year period she bore Joseph’s two sons. So this is not your run of the mill saga of marital infidelity. Dolly’s story is so complex and so unimaginable that it deservers its own page. And so a link to that story will be provided at the end of this page.

Dolly never appears to have lived in Maine for any extended periods of time and she most probably never returned after the birth of Isaac in 1794. But Isaac’s father Joseph lived on in Gray for nearly 50 more years after Isaac’s birth, dying at the age of 92, with no evidence of him having married again.

As it was too sad to imagine him living alone all of these years, perhaps heartbroken or bitter, I began to imagine, in my earliest ponderings about this bizarre story, a scenario in which Joseph spent these later years surrounded by family – his father and step-mother, his siblings and their families, his three children with Margaret and his two sons with Dolly, followed by multitudes of grandchildren. And so this lovely image of New England farm life perfectly suited my fantasy.

And then, not only did my fantasy come to life, it was greatly improved! Further research told me that even when Joseph’s sons with Dolly had established their own farms in far off communities, not only did they visit, they often stayed long enough for many of his grandchildren to be born there. Records show that three of Joe Jr’s children and five of Isaac and Lovina’s were born in Gray. So our Joseph was indeed never alone – surrounded by his own children and grandchildren – as well as the children and grandchildren of his siblings. 😊 My wishes come true.

Both of Joseph and Dolly’s sons – Joe Jr and Isaac Jennings – would go on to marry women from Hebron, the next town of significance for our ancestors. But before we leave Dolly a debt of gratitude must be paid to her, for the simple reason that no matter how disturbing her actions seem to us today – no matter how reckless, unstable or merely desperate they may have been, without her our ancestor, Isaac Jennings Cummings, would never have existed, and so would never have married our Mayflower ancestor, Lovina Caldwell, which means that none of us would be here now to marvel at this astonishing heritage. So, thank you, Dolly.

HEBRON, MAINE – where our Plymouth and Salem ancestors meet.

In 1781 the last of our Mayflower ancestors, Suzanna Perkins, was born in Plymouth to Joseph Perkins and Sarah Cushman – bringing together the bloodlines of all 12 of our Mayflower ancestors. But within months of Suzanna’s birth they moved from Plymouth to Hebron, Maine where she was christened and raised, becoming – after six generations – our first Mayflower ancestor to grow up and marry outside of the Plymouth colony.

Suzanna would go on to marry Phillip Caldwell, whose parents had migrated to Hebron sometime in the 1790s. It’s unclear still if any of these families – the Perkins, the Cushmans or the Caldwell’s purchased lands or were granted them for military service. It’s also unclear whether they were farmers, tradesmen or government officials. Only when Philip and Suzanna’s second child – our ancestor, Lovina – marries our Salem ancestor, Isaac Jennings Cummings, and settles in nearby Minot, can we be certain that they were farmers.

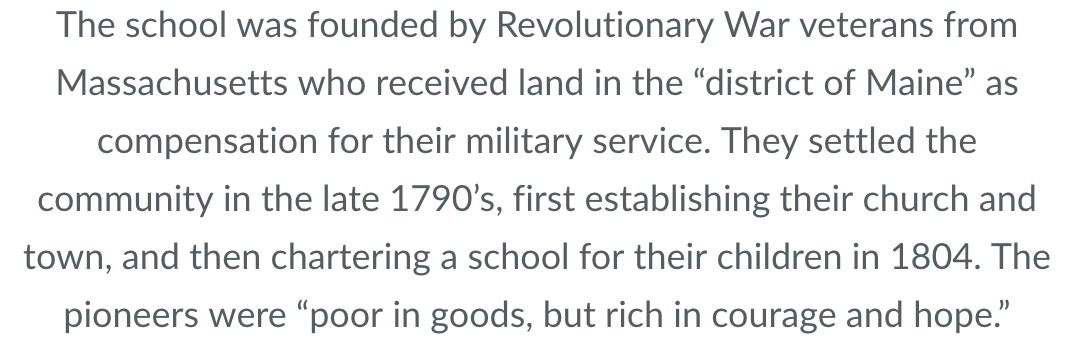

But this excerpt below, which focuses on the establishment of the Hebron Academy in 1804, suggests that the community was far more than a simple farming one. It also suggests that the Caldwells, the Perkins and the Cushmans were Revolutionary War Veterans and that many of their children might have attended this Academy.

THE HEBRON ACADEMY

“Poor in goods” however, I’m less and less convinced. It appears that all of these families were doing very well, but their still strong Puritanical beliefs insisted that they claim humility, with little outward expression of wealth.

But the clearest evidence that all three of these families lived in Hebron comes from this Census report below which lists the earliest families who lived in Hebron between 1790 and 1850. It includes our Perkins and Cushman ancestors from the Plymouth Colony and the Caldwell family from the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Additionally this Caldwell family gravestone brings all of these family names together: Phillip Caldwell, followed by his wife “Susan P” (Suzanna Perkins), then at the bottom their daughter, Lovina and above her, Isaac Cummings, her husband and our ancestor – the son of our mysterious Dolly Ingersoll.

PARIS, MAINE

Our next stop is Paris, Maine where Phillip and Suzanna married and gave birth to their enormous brood of children. But before we move on to Paris, Phillip Caldwell’s ancestry deserves some attention – both for its remarkable lineage which dates back to 12th century Italy and for the fascinating evolution of the Caldwell name.

The first Caldwell name was recorded in Turin, Italy as Calweldi in 1100.

(Turin, BTW, is the birthplace of our Italian great grandmother Rosalina Ferrari 😊)

By 1150 the name had become Caulwel in France, and would remain so for 10 generations

until Alexander Thomas Caldwell moved to Scotland.

His son William Bruce Caldwell, would marry Lady Elizabeth Mary Wallace,

hinting still at a faint whisper of nobility, until…

Their fifth child, John Caldwell, became a merchant and married Irish lass, Mary Sweetenham.

They had 7 children, all born in Northern Ireland.

Their eldest child, John Caldwell, Jr was born in 1624 and took up the trade of weaver.

In 1643 he immigrated to BOSTON and in 1656 married Sarah Dillingham.

They moved to Ipswich and had 9 children.

For the next four generations the Caldwell’s (all named John but for one William)

would inhabit Ipswich, until the last John ( our ancestor) married Dolly Hoyt.

John and Dolly had five children, born variously in Ipswich, Salem and Haverhill

where in 1773 our next ancestor, Phillip Caldwell, was born.

Then at some point during the 1790’s John and Dolly moved with all of their children to Hebron.

All of Dolly and John’s children were born during the chaos of the Revolutionary War which might explain their births in different locations.

Also John may have fought during the war, entitling him to land in Maine that was granted during the 1790’s.

But whether he was granted or purchased land in Hebron, John and Dolly Caldwell would live out their lives there,

as would the parents of Suzanna Perkins, the woman their son Phillip would marry.

PARIS, MAINE

Phillip Caldwell and Suzanna Perkins married in Paris, Maine in 1798 and almost all of their 16 children were born there. Moreover, almost all of them would survive into middle or old age – an unusually robust statistic. Their hearty well-being might suggest that Caldwell was anything but a struggling farmer, and more likely a successful merchant, with significant political power. The town of Paris had been incorporated in 1793 and by 1804 had become the Oxford County Seat, with a fast growing population. Between the birth of our ancestor Lovina in 1801 and her marriage to Isaac Cummings in 1819, the population more than doubled from 800 to 1800 residents. And so the success of this town may further help to explain why so many of Phillip and Suzanna’s children survived so well and for so long – including Lovina, who lived to be 84.

This antique post card above of Paris depicts the town long after Lovina and Isaac would have met there and married – notice the electric poles. But it may well have been recognisable to Lovina in her later years – living as she did until 1883.

Historical records tell us that Paris, after becoming the Oxford County seat, developed into a thriving community. It is still noted today for its scenic beauty and excellent pasturage, including some of the state’s best apple orchards, livestock and dairy farms. In 1973, Paris was added to the National Register of Historic Places for its fine examples of Federal and Greek Revival architecture. And Paris is also noted for being the home of Hannibal Hamlin who served as Abraham Lincoln’s vice president during his first term.

But how did Lovina Caldwell – our Mayflower descendant – and Isaac Jennings Cummings – our Salem descendant – meet?

Paris, Maine by 1819 had been the vibrant county seat for 15 years when the young sons of Dolly Ingersoll and Joseph Cummings – Joe Jr and Isaac – were coming into adulthood. And even though it was a good day’s ride from Gray to Paris, these young men would certainly have made the trip for both practical concerns as well as social curiosity.

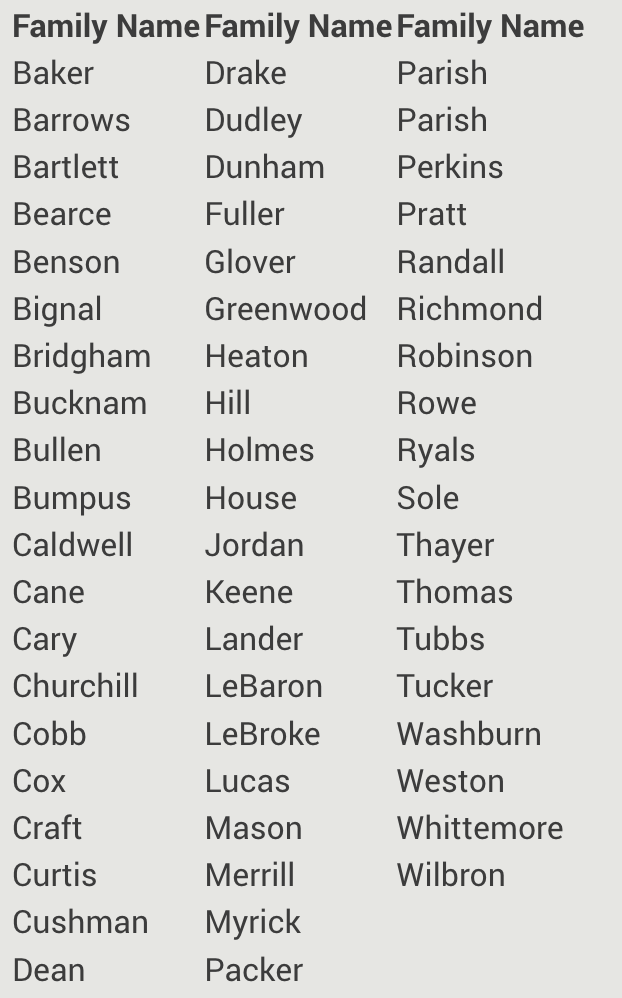

And more likely than not it was during one of their adventures that Joe Jr met and later married Ruth Thayer, a resident of Hebron. And more than likely the Caldwells – as Hebron residents – with their marriage age granddaughter (our Mayflower ancestor), Lovina, would most certainly have attended the wedding putting Lovina in the right place and time to meet the groom’s brother – our Cummings ancestor, Isaac. This is all pure “meet cute” fantasy on my part, but certainly within the realm of possibility.

I just found these gravestones for Ruth Thayer and Joseph Jr Cummings in Hebron and looking forwarding to visiting them along with the Caldwell memorial stone above. 😊

MINOT, MAINE

But however Isaac and Lovina met, once married they moved to Minot – a short distance from Paris, where five of their eleven children were born, including our ancestor – their 8th child – Albert Webster Cummings.

My first searches for Minot suggested a small and rather poor community until I came across a fascinating article, The History of Minot which described this 19th century village as a thriving and self-sustaining community, which at one point boasted 25 one-room school houses and 6000 sheep! See: minotme.org/index

But for me the best discovery was the following:

“The first Methodist church at Minot Corner was built in 1835 and is still very active with weekly services.” This would have been six years after the birth of Albert Webster Cummings, and so just the evidence I’d been seeking for the roots of Albert’s later passionate and life-long commitment as a Methodist minister.

The church in this photo is a reconstruction of the original 1835 church, using the original timbers.

But if city life had bode well for the survival of the Caldwell children, farm life for Lovina and her husband, Isaac Jennings Cummings, was not so fortunate. Isaac would die in his sixties, leaving Lovina – who survived to 83 – to run their farm while raising their 10 children – half of whom met untimely deaths in childhood or young adulthood. Her granddaughter Estelle described Lovina in her letters as a powerful, no-nonsense woman and a well-loved nurse-made to many in her community – tending with care to the needs of so many despite her own heartbreaks.

But before we leave Maine and move on to Estelle’s marvellous letters, I want to share the following wonderfully descriptive account of 19th Century Farm Life in Maine, precisely during the years that Lovina Caldwell and Isaac Jennings Cummings would have been raising their children and running both their own farm in Minot and Isaac’s father’s farm in Gray. Well worth the read so I hope you give it a go 🤓.

Excerpt from

Maine Memory 1820-1850: A New State and Prosperity

Maine farms were typically small, family-run operations, averaging around 100 acres, and they faced formidable natural obstacles, including geographical isolation, thin soils, dense forests, and unpredictable weather.

They grew a variety of grains along with potatoes, corn, fruits, and vegetables, and raised poultry, cattle, and sheep. After the fall harvest men produced hand-crafted items like clocks, buggy whips, furniture, horse collars, barrels, and shingles, and women made brooms, baskets, and palm-leaf hats and wove cloth or took in cut fabric or leather to sew into clothes or shoes.

“Mixed husbandry,” as this approach to farming was called, was a response to Maine’s small, easily saturated markets and to the great risk in raising crops in Maine; if one source of income failed, another took its place. Workers in other areas – fishing, lumbering, and more – use a similar tactic of taking on a variety of jobs to ensure economic viability.

Woodcut of 19th Century Maine Apple Farm

With subsistence as a primary goal, the farm family focused on the long winter months when humans and livestock lived off the bounty of the previous season’s work. Households were fortified with bushels of potatoes, oats, wheat, buckwheat, and corn; barrels of salt pork, corned beef, and sausage; bins of vegetable and root crops, crocks of butter, loafs of maple sugar, rounds of cheese, and jars of preserves.

Women’s work was central to this subsistence-based system. Mothers and daughters ran the farm in winter when husbands and sons worked in the woods, and they exchanged various products and skills with neighbors to supplement the family’s harvest. They extended the bounty of one season through the next by processing meat, grains, and produce, and they nurtured the farm’s primary labor force, instilling the strong work habits so vital to the farm’s success.

While husbands and sons worked in the fields, barns, and woodlots, wives and daughters made meals, milked cows, churned butter, fed livestock and poultry, carried wood, tended smaller children, mended grain sacks, washed and ironed clothes, cleaned milk pans, tilled the garden, gathered fruit, and, when time permitted, cleaned the house. And to augment their self-sufficiency and their limited market purchases, men and women bartered skills like blacksmithing, candlemaking, weaving, dressmaking, health care, and carpentry with neighbors; they shared machinery, exchanged use of pastures, borrowed tools, and stood by others in birth, sickness, or death.

All in all this article depicts an extraordinarily rich – albeit challenging – life

and one that I truly hope our Maine ancestors actually experienced.

Ah! But I’ve completely forgotten to tell you why Maine is so signifiant in US History.

Maine had been a pro-abolitionist territory long before it became a state. And the Methodists themselves were strong abolition supporters.

But when the Missouri territory wanted to enter the Union as a slave state the young US government

– wanting to keep the balance between slave and free states – made the proposal that Maine could enter as a free state,

but only if Missouri could enter as a slave state – hence the Missouri Compromise.

And so Maine – despite their opposition to any state being a slave state – in order to become a state and a free one – bit their tongue and made the deal.

Link soon to follow with the story of how our last Cummings ancestors ended up in Minnesota –

their bloodline much improved – I humbly believe – through its intermingling with the DNA of Mary Towne Easty

and our Mayflower ancestors. And if not “improved” certainly fortified with the DNA of our unfathomable Dolly Ingersoll.

I mean, the girl had stamina! 🤣

But first, as promised, click here for

the remarkable story of our great great great great grandmother,

DOLLY INGERSOLL

Your comments are welcome. Please contact me at [email protected]