DOLLY INGERSOLL

THE UNFATHOMABLE STORY OF OUR GREAT GREAT GREAT GREAT GRANDMOTHER

And a Tale of Two Towns – Gray, Maine and Newburyport, Massachusetts

I introduced Dolly’s story in my previous story (four stories, really) about Maine. But as I learned more about her, the story became so long and complex that it was pulling focus from the other stories, so I decided that Dolly needed and deserved her own page. She also needed her own page because her story takes us back into Massachusetts and specifically the bustling port city of Newburyport – a world away from the small farming villages our Maine ancestors inhabited – and specifically the village of Gray where she forever impacts the lineage of our Cummings ancestors. We will never know for certain what motivated her bouncing back and forth between these two worlds and yet the myriad facts which we can confirm about her life provide an abundance of clues that make for, at minimum, rich speculation. And that is what this page is all about – presenting the facts and then speculating on their possible significance.

This “Outdoor Tea Party”, Illustrated by Howard Pyle (1853-1911) depicts Colonial New England Society, in the 18th century, and so may reflect something of the world into which Dolly was born and into which she later married. Compare this with the farm life Dolly was undoubtedly exposed to. And whether or not she actually lived it she certainly flirted twice with making this her life.

Here is a quick recap of how Dolly fits into our Cummings family history.

Dolly’s story is linked with our 6th generation Cummings ancestor, Joseph, the great great grandson of Mary Towne Easty (one of the last victims of the Salem Witch Trials). He was born in 1751 in Topsfield, Massacusetts – where the Cummings and Town families were united through several marriages. But before he was 15 his family moved from Topsfield to Gray, Maine where at 24 he married Margaret Sanger. They had four children – one of whom died in infancy and three more who lived to adulthood. But one year after the birth of their last child Margaret died in 1782 leaving Joseph to raise their three young children on his own.

Because of so much untimely death during colonial times it was common for widows and widowers to marry again, often within months of a spouse’s passing. But another woman would not appear in Joseph’s life for several years, when records show the births of two more sons, Joseph Jr, born in 1791, and Isaac Jennings (our ancestor), born in 1794. The mother of these boys was Dolly Ingersoll, born in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1755.

For many years Mom and I just accepted the name as being another one of so many Cummings wives without further investigation. But in my recent research and strategy to also “follow the women”, a confluence of several oddities peaked my curiosity:

1) no marriage record

2) no specific birth records for our ancestor, Isaac, and

3) the fact that Dolly died and was buried – not in Gray where Joseph died and was buried 27 years later – but 100 miles away in Newburyport.

My curiosity thusly peaked, I began to dig and was rewarded with surprises that I’m now not only used to – but highly addicted to.

The Mysterious “Marriage” of Joseph Cummings and Dolly Ingersoll

Minimal math revealed that Dolly was 36 and then 39 when her two sons with Joseph were born, so I checked to see if she’d been married before and that’s when the first surprise came. Not only had she been married before, she was married at the time she was bearing children with Joseph. She was married to Enoch Greenleaf, a widower, of Newburyport, Massachusetts and had been since 1789. And the second shock was the discovery that between 1790 and 1795, she was intermittently bearing children with both Enoch and Joseph.

Here is Dolly’s mind-boggling history of motherhood:

Dolly gives birth to her first child with Enoch Greenleaf in Newburyport, Massachusetts in July 22, 1790 – George Greenleaf.

Less than one year later she gives birth to her first child with Joseph Cummings in Gray, Maine in May 31, 1791 – Joseph Cummings, Jr.

Her second child with Greenleaf was born 9 months later on January 18, 1792, in Newburyport – Dorothy (Dolly) Greenleaf.

She then gives birth to another child with Greenleaf on October 30, 1793 in Newburyport – Enoch Greenleaf, Jr.

Then sometime in 1794 she gives birth to a second child with Cummings somewhere in Maine – our ancestor, Issac Jennings Cummings.

And finally one year later she gives birth to her fourth child with Greenleaf on July 20, 1795 in Newburyport – Caroline Greenleaf

This would would have been a difficult feat – considering how close some of the births were – if Greenleaf and Cummings lived somewhere near one another. But the distance between the two locations was nearly 100 miles. So I wondered if these dates could simply be incorrect. Yet several different search sites are all in agreement about dates and parentage.

There is no evidence of any more children born to Dolly – fathered by either man – and no evidence of further marriages for any of them. There is also no evidence that Dolly ever returned to Maine. She appears to have remained in Newburyport where in October 1797 her four year old son, Enoch Jr., died followed by Enoch himself three months later in January 1798 – at the age of 40. Dolly then died eight years later in 1816, also in Newburyport. and is buried next to Enoch and his first wife – Dolly’s gravestone identifying her as Enoch’s wife. And so with all of these details fully clarified it was now certain that Dolly Ingersoll and Joseph Cummings were never married.

So… how does one begin to make sense of this bizarre “marital” and maternal history?

Here is one of the first questions that came to mind: Had these children been in some way transactional?

Both men were widowers. Joseph Cummings had been widowed for 9 years when his first child with Dolly was born. And Enoch Greenleaf had lost his first wife 18 months before his first child with Dolly was born. And initially I could not find a marriage record for Dolly and Enoch. So I began to think that Dolly might have been an indentured servant, providing children to men who, for whatever reason, did not want to marry again, yet needed children (heirs) or, in Joseph’s case, more children. However, I couldn’t find any evidence that such a practice was even a thing.

Even so I dug into Dolly’s lineage, looking for evidence of her having been an indentured servant.

And very quickly I discovered that Dolly was anything but. She was instead the descendant of minor English nobility, dating back to 15th and 16th centuries. Her first New Ingersoll ancestors had arrived to Plymouth in 1629 and had stayed briefly in Salem before settling in Gloucester where they’d received several generous land grants from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. And Dolly’s paternal great great grandfather, Lt. George Ingersoll, was a renowned war hero in Falmouth (now Portland) Maine during King Phillip’s War, as well as an influential statesman both there and in Gloucester. Moreover one of her maternal great great grandfathers, Thomas Rigg, was the first Gloucester school master, who – trained in England as a scribe – was also Gloucester’s town clerk for 51 years. And another of her maternal great great grandfathers, Deacon Thomas Low, was noted for defending John and Elizabeth Proctor in the Salem Witch Trials.

Dolly was born in Gloucester, MA, to Medifor Ingersoll and Dorothy Low – the second of four children: Nathaniel (1753), Dolly (1755), Zebulon (1757) and Rebecca (1759). But sadly Medifor died at the age of 30 (a prisoner on a French ship at the height of the French and Indian War – which was actually between the British and French colonies – with various native tribes backing each side). Devastated I imaging by his death, Medifor’s 26 year old wife was left alone with three young children and a newborn may have left Gloucester and moved to Newbury to be with her mother, Abigail Rigg Low, and two of her sisters who had each married Newbury men.

There is no evidence that Dorothy married again but there is also no record of the date or place of her death, so we don’t know for certain what the childhoods of Dolly and her siblings were like or where they were living. The first evidence we have of the family after Medifor’s death is Zebulon’s marriage in 1781 (at the age of 24) in Newberry. This was followed one year later by the marriages of both Nathaniel and Rebecca (oddly one day apart from each other). However Rebecca’s marriage was in Gloucester, while Nathaniel’s was in New Gloucester, Maine – 100 miles away – where he’d moved sometime before. These three siblings would remain where they married throughout their lives, each having multiple children, most of whom also remained where they were born. Only Dolly would stay single for several more years, until the age of 34 when she married Capt. Enoch Greenleaf, two years her junior and the son of the Honourable Capt. Jonathan Greenleaf – a wealthy ship builder and influential statesman in Newburyport. Why she waited so long to marry is among the many mysteries of her life. Was her mother not well and needed her care, or is it more complicated?

So how might Enoch and Dolly have met?

,We know that Enoch was a contemporary of Dolly’s younger brother Zebulon. They were the same age, both had served in the Revolutionary War and both later owned property and businesses in Newburyport and neighbouring Rocks Village in Haverhill. So it is quite possible that through her brother, Zebulon, Dolly met Enoch.

But however they met, this seems to have been an appropriate marriage for them – both decendents of high status families in Newburyport and Gloucester. And within a year of their marriage, their first child, George – named after Dolly’s illustrious ancestor – was born. So what went wrong? So wrong that she was compelled to abandon both husband and newborn and flee to Maine where, within less than a year, she’d give birth to her first child with Joseph Cummings.

And what then compelled her to leave Joseph immediately after the birth of Joseph Jr and not only return to Enoch but have two more children with him? This portrait could well represent the family before their 3rd child was born and before she returned again to Maine, where she bore a second child with Joseph. But any even bigger question is…

How did Dolly and Joseph Cummings meet!?!

More digging revealed that Dolly’s older brother Nathaniel had purchased a farm in New Gloucester, Maine – just six miles north of Gray around the same time that Joseph Cummings lost his wife Margaret in 1782. And so one might guess that in these small farming communities Nathaniel and Joseph were probably acquaintances, if not friends, and so it’s likely that through him Dolly met Joseph.

I had also wondered how Dolly managed the 100 mile trek between Newburyport and Gray, Maine – imagining a buggy bumping over unpaved roads for perhaps days – until I learned that, before the railroads, most travel up and down the coast was done by boat. And as Newburyport is clearly a port town and Portland, Maine is the port city closest to Gray – home of Joseph – and New Gloucester – home of Nathaniel, her frequent trips seemed more plausible.

But when did they meet?

It’s hard to believe that their first encounter occurred within a month of Dolly giving birth to her first child with Enoch in Newburyport and that this encounter resulted in a child nine months later. So my guess is that Dolly and Joseph had met long before she married Enoch – perhaps during a much earlier visit to her brother in New Gloucester. And they may have struck up a friendship – remember Josephs mother Mary was from Dolly’s birthplace – Gloucester.

(Thank you North Wind Picture Archives and Alamy Stock Photos for this woodcut of an 18th century farmer in his cornfield praying for rain.) Maine has no shortage of rain but I like to imagine Joseph looking something like this.

So I now have strong evidence that Dolly may have met both Enoch and Joseph through her brothers, Zebulon and Nathaniel. But there is still nothing to explain her bizarre maternal history with these two men.

Unable to let go the Mystery of Dolly Ingersoll

I cannot imagine that we will ever understand Dolly’s story – nor the parts Enoch and Joseph played in it. Still there are several of clues from which a number of possible scenarios might emerge. And so to satisfy this burning curiosity, I’ve begun a fictionalised account of her life, with the challenge of doing so while rigorously adhering to all that is known about everyone directly or tangentially involved. This is no small feat considering how unfathomable what is known actually is. At the same time, the only way to account for how very unfathomable it all is, is to create characters and circumstances capable of justifying such unfathomability – which is great fun, indeed! And when I’ve had my way with all of this tantalising material I’ll provide a link to my creation both at the bottom of this page as well as on the introductory page to Our Family Stories.

As I collect information, it seems to me that the madness in this triangle revolves primarily around the characters of Dolly and Enoch and the dynamics of their most certainly fraught marriage. It’s even possible that Joseph may have been little more than collateral damage – a kind of hapless bystander – drawn in by his mere propinquity* to Dolly.

* Wanting to confirm my accurate use of “propinquity” I googled it and found this example of usage which couldn’t be more apt for Joseph and Dolly:

“he kept his distance as though afraid propinquity might lead him into temptation”.

But we know that Joseph did not keep his distance, for if he had none of us would be here today! But very little is actually known about Joseph – especially anything that could give us clues to his character. Moreover importantly while we find his lineage fascinating – the descendent of the grandparents so intimately linked to the Salem Witch Trails – more likely than not this lineage would either have been unknown to him or, if known, a topic of shame.

So it’s become my guess that Enoch is the character we need to better understand in order to make any sense of Dolly’s story. And because of the status of the Greenleaf family in Newburyport there is no shortage of information about him. And the more I learn, the more a character begins to emerge that could easily exacerbate what may have been Dolly’s fundamentally erratic and impulsive nature.

AND THIS IS WHAT I LEARNED ABOUT HIM

Enoch matrimonial history: While many of Enoch’s contemporaries were marrying in the midst of the war in their early 20’s – including Enoch’s brother Moses and both of Dolly’s brothers – Enoch remained single. And when he finally did marry in 1784 – nearly a year after the conclusion of the war – he chose a woman with no known social standing. Records provide almost no information about Mary Stone. There are no specific birth or death records for her parents, no siblings and no known ancestors beyond her parents. Mary died five years later in January of 1789 without having any children, and seven months later Enoch married Dolly. Then over a six year period they had four children – despite her leaving twice and having two children with another man during the same six year period.

His professional life: Even though Enoch’s father – the Honorable Jonathan Greenleaf – was a wealthy ship builder and influential statesman, Enoch followed neither path. There is some evidence of him having worked for a time after the war as a shipwright for his father but later is only known to have “owned a store”. Records show that Enoch’s older brother Moses also worked for their father, but then moved to New Gloucester, Maine (as Dolly’s older brother Nathaniel had done) to take up farming. This might suggest difficult relations between Jonathan and his sons. It also suggests that the Ingersolls and the Greenleafs knew each other.

His health: Enoch died at 40 of consumption, weeks after the death of his four year old son, Enoch Jr, and one month shy but ten years to the day of his first wife. He died on January 9 and she on February 9. Moreover, his death occurred at a time when consumption was considered a disease either of the poor or of those who abused alcohol and tobacco. And we know that he wasn’t poor.

His siblings: Enoch was one of six sons – three of whom died in childhood and another in young adulthood. Only his brother Moses lived longer than Enoch, dying of cancer at 57, while their powerful father outlived them all – only dying in his late seventies. The only siblings to outlive this powerful patriarch were two of Enoch’s sisters, both of whom lived into their 80’s.

His father: The Honourable Jonathan Greenleaf appears to have been a powerful figure with a lineage of prominent military and political leaders and one prominent reverend, dating back to the arrival of the first Greenleaf to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634. And even though both of Jonathan’s parents died young leaving Jonathan an orphan at the age of four, this did not stop him from achieving even greater military and political success than his ancestors. Not only did he build a highly lucrative ship building business, he was instrumental in the incorporation of Newburyport as a township separate from the nearby farming community of Newbury. And he is mentioned in numerous periodicals of the time relating to Newburyport’s role as a model for the formation and training of militias at the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

What stands out to me most is the disparity between the accomplishments – and longevity – of Jonathan and his sons So it’s hard not to imagine that Enoch was on poor terms with his father. I’m getting ahead of myself in making stuff up, but I can’t help but wonder if Jonathan (whose own wife had a lengthy lineage) was critical of Enoch’s choice of wife, – creating a rift between father and son so devastating that Enoch either chose to leave or was forced out of his father’s business.

How Enoch then came to marry Dolly (whose lineage would have rivalled the Greenleaf’s) soon after his wife’s death will certainly be an entertaining challenge to invent. For if Jonathan had opposed Enoch’s marriage to Mary, how might he have responded to Dolly? And how might that have impacted their marriage? But I’ll save such speculations for my fictionalised account, and continue here with more material evidence which I can use to construct it: Real Estate 🤣

As significant as the three main actors are to this story, the two locations in which it unfolds – Newburyport, Massachusetts and Gray, Maine – seem to me to be every bit as significant. These places have stories of their own and I’ve had exceptional luck in finding a wealth of fascinating historical reflections, images and maps of the two towns to help bring my imagined tale to life.

NEWBURYPORT and GRAY, MAINE

The Dramatic Backdrops to Dolly’s Story

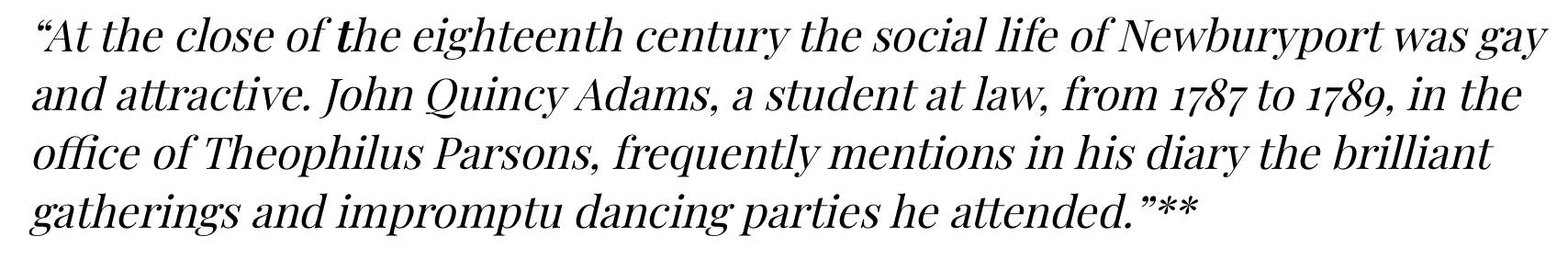

The late 18th century of Newburyport was known as its Golden Age, and as such was as opposite as one can imagine from the simple life of a farmer in Gray, Maine. The following excerpts from a history of Newburyport describe it as a world of wealth, refinement, and elegant parties – as well as being the stomping grounds of a young John Quincy Adams (future US president – then an apprentice law student).

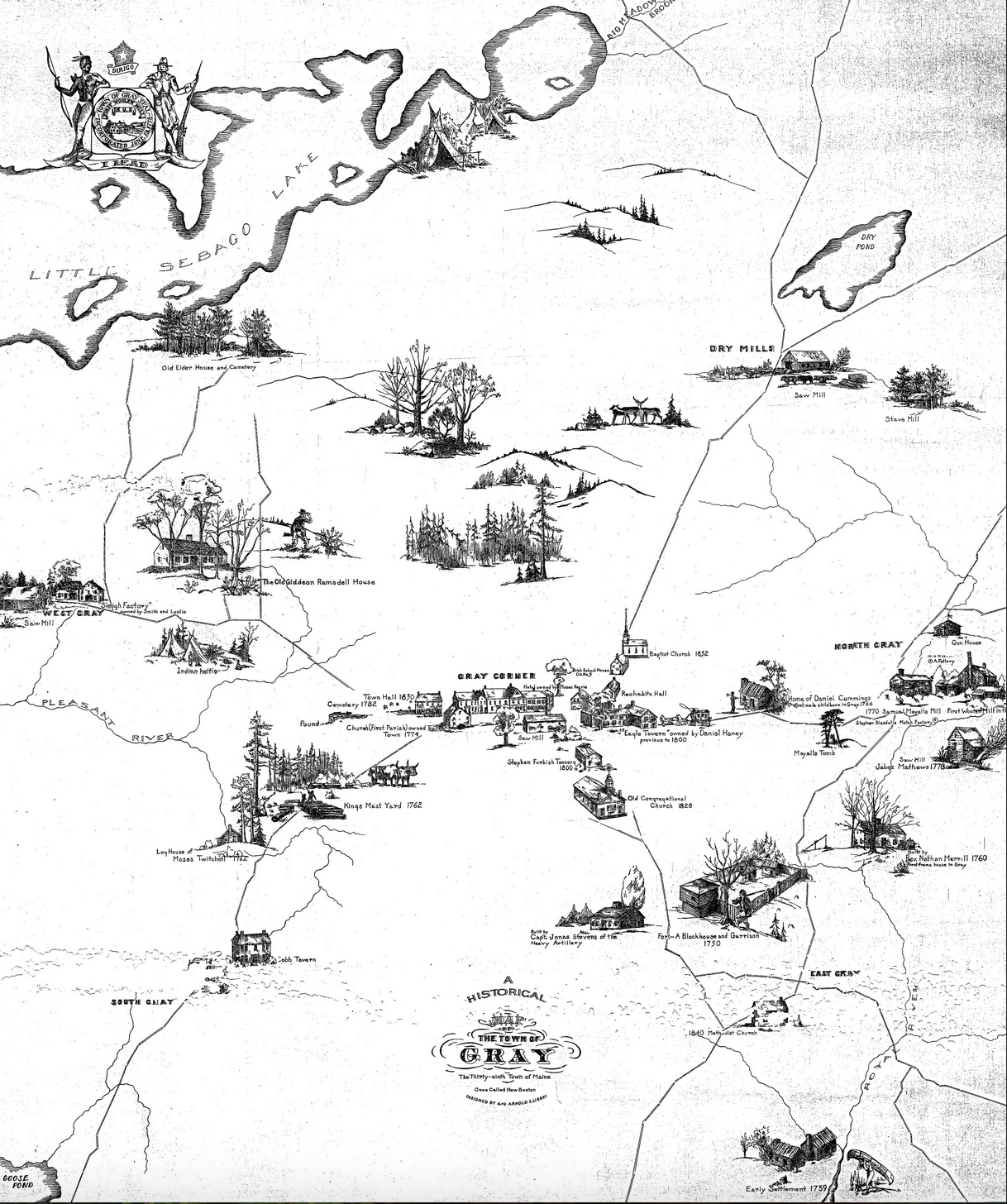

Compare these descriptions to the antique map below of Gray, Maine – where Joseph lived most of his life

and where his sons with Dolly – Joseph Jr. and our ancestor Isaac Jennings – most probably grew up.

Historic hand-drawn map of Gray, Maine

This is a most happy find – drawn to commemorate Gray as the 39th town in Maine to become incorporated in 1778 – some ten years or more after the Cummings moved there. Because of the map’s stunning and exquisitely personalised detail, it deserves the huge amount of space I’ve given it below. It also demonstrates dramatically how stark the differences were in the two world Dolly was bouncing between. But more importantly, for us, it identifies the first Cummings farm belonging to Daniel and Mary after their departure from Topsfield. Scroll down for a zoomed in image of the farm itself.

This zoomed image above will help you locate the Cummings farm on the centre left-hand side of the large map above. The farm itself is clearly identified as: “Home of Daniel Cummings” and the birthplace of “The first male child born in Gray 1766.”

I especially love the primitive drawing of the farmer with hoe, adjacent to the Cummings’ house – one of only five figures depicted among over 30 structures, and with only three identified owners – indicating the significance of the Cummings family at that time in this community.

Notice that the Cummings farm is just to the left of the Mayall Woollen Mill – which is noted for being the first successful water-power driven mill in North America.

The location of the ruins that remain of the Mill are pinpointed on Google Earth in the image above.. The numerous structures NE of the pin may have been the location of the mill itself and just further NE the location of the first Cummings Farm. I’m surprised that the area is still so rural. It will be fun to see in person.

And this American Primitive drawing on the left of an 18th century farm kitchen might well reflect the Gray kitchen filled with the many women who would have made up the extended Cummings family.

And if the Cummings farm was half as humble as the map depicts, and if this farm kitchen reflects in any way what would have been expected of Dolly had she chosen at any point to stay with Joseph, it’s hard to imagine her adjusting to this life, or ever being accepted by Joseph’s family into it.

The only evidence that Dolly ever lived in Gray is the record of the birth of her first son with Joseph there on May 31, 1791. In contrast our ancestor – Isaac Jennings – is only vaguely recorded as the year 1794 and the location Maine. How much time Dolly actually spent in Gray is only a guess. But here below are photographic clues as to where Dolly most likely did spend most of her time.

aymay

NEWBURYPORT, MASSACHUSETTS

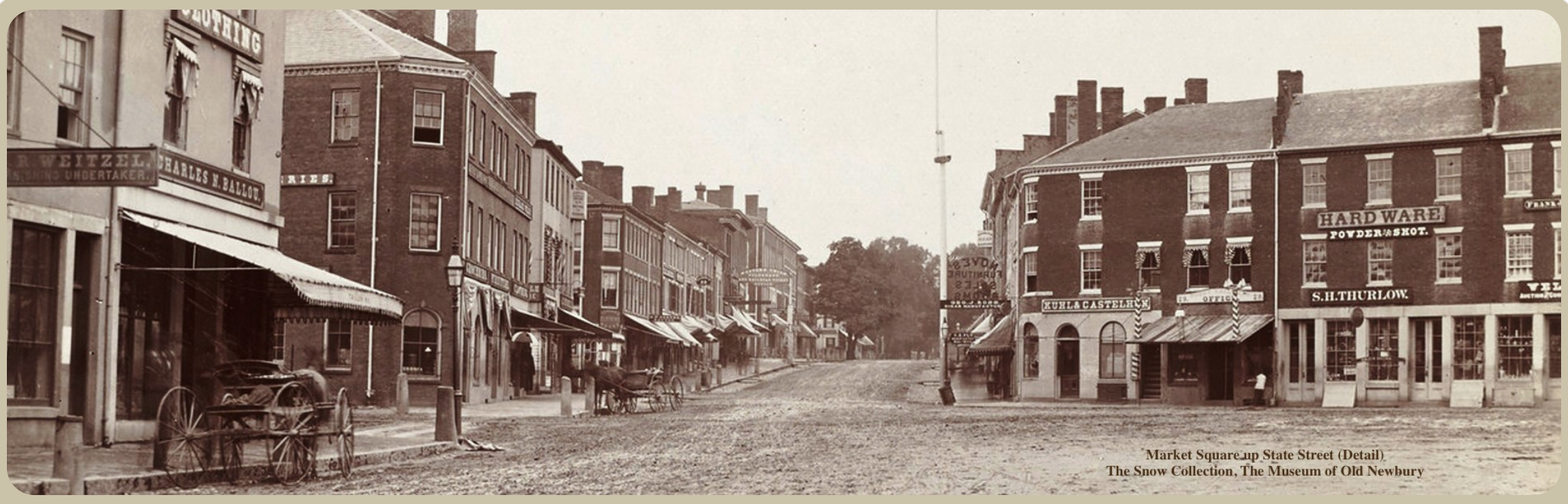

Below is an antique postcard of the Historic Market Square in Newburyport. Because it is a photograph,

it’s most probably from the mid 19th century. Yet it may still reflect something of the time when Dolly lived there.

And below are photos of two historic homes – still standing today – which were once owned by the Greenleaf family in Newburyport. The home on the left is identified as belonging to Enoch’s ship father, Jonathan. And if the dates refer to the years they were built, the house on the left indentifies the year Enoch and Dolly’s first child was born, while the date for the house on the right is the same year that Enoch died. So more research is necessary to know if Dolly ever lived in either of them. But whether or not she did, this was the world she was a part of.

And here below is the current map of Newburyport where we can see both of the streets where these houses still sit – Green Street and High Street – and the Market Square at the top of State Street (a triangle really in the upper right hand corner). And in the bottom left corner is the Old Cemetery where Dolly and Enoch are buried – adjacent to Greenleaf Street – named for Enoch’s father, Jonathan. (Tis my plan is to stay in one of the inns identified in PINK on this map 🙂

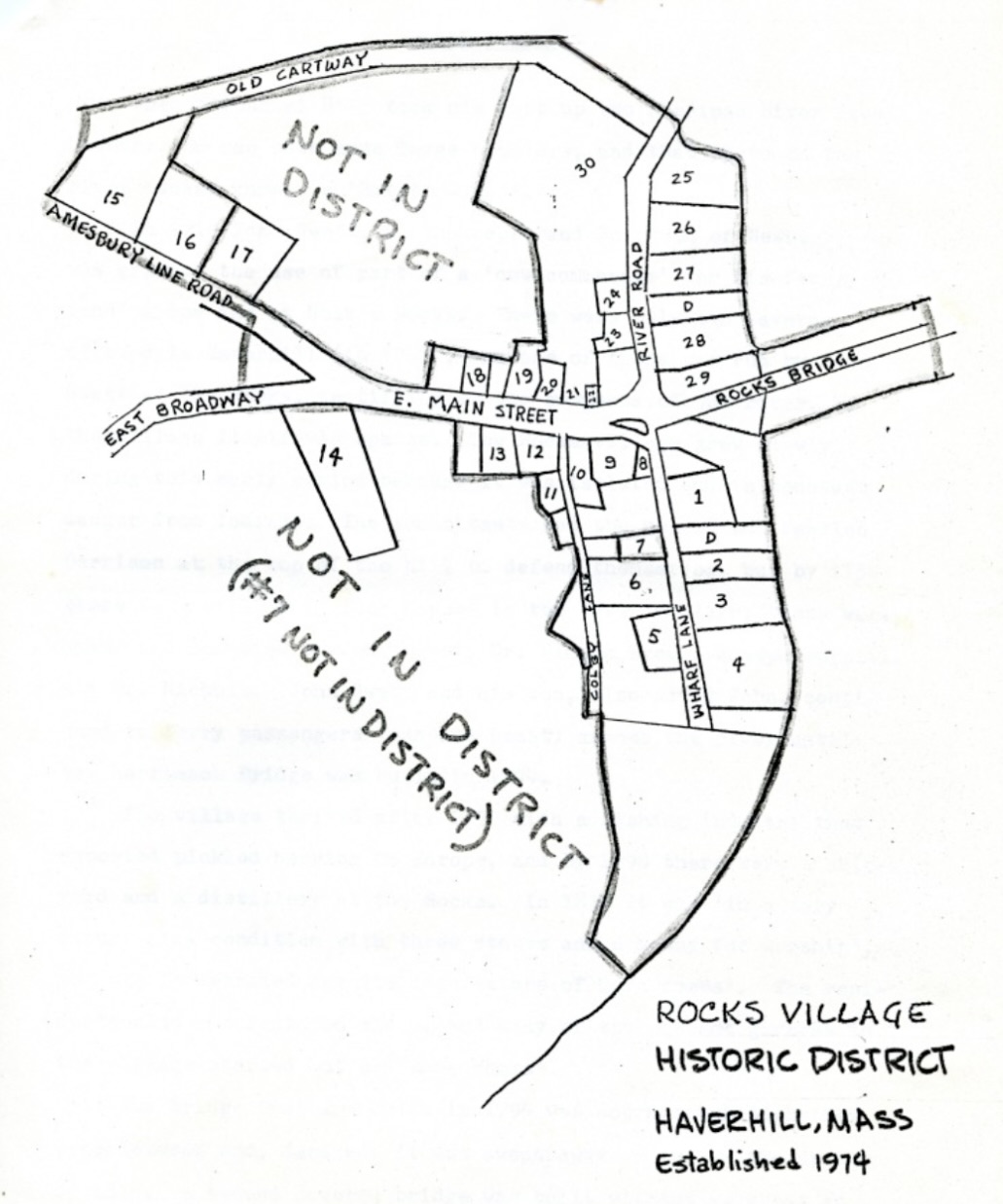

More recent evidence records Dolly as having purchased a house and land in nearby Rock’s Village the year she and Enoch married – a house which she later sold to her brother Zebulon in late 1803 – nearly four years after Enoch’s death. Moreover, Dolly and Enoch’s marriage is recorded in Haverhill – the town which Rock’s Village is a part of. Goggle describes Rocks Village as a refined and elegant bedroom community of Newburyport – which boasts still standing many of fine homes of the 18th century.

It also seems noteworthy that they married in Haverhill, not Newburyport, and that Dolly purchased the house, not Enoch – perhaps indicating a substantial inheritance from her family, while also suggesting a kind of disinheritance from his.

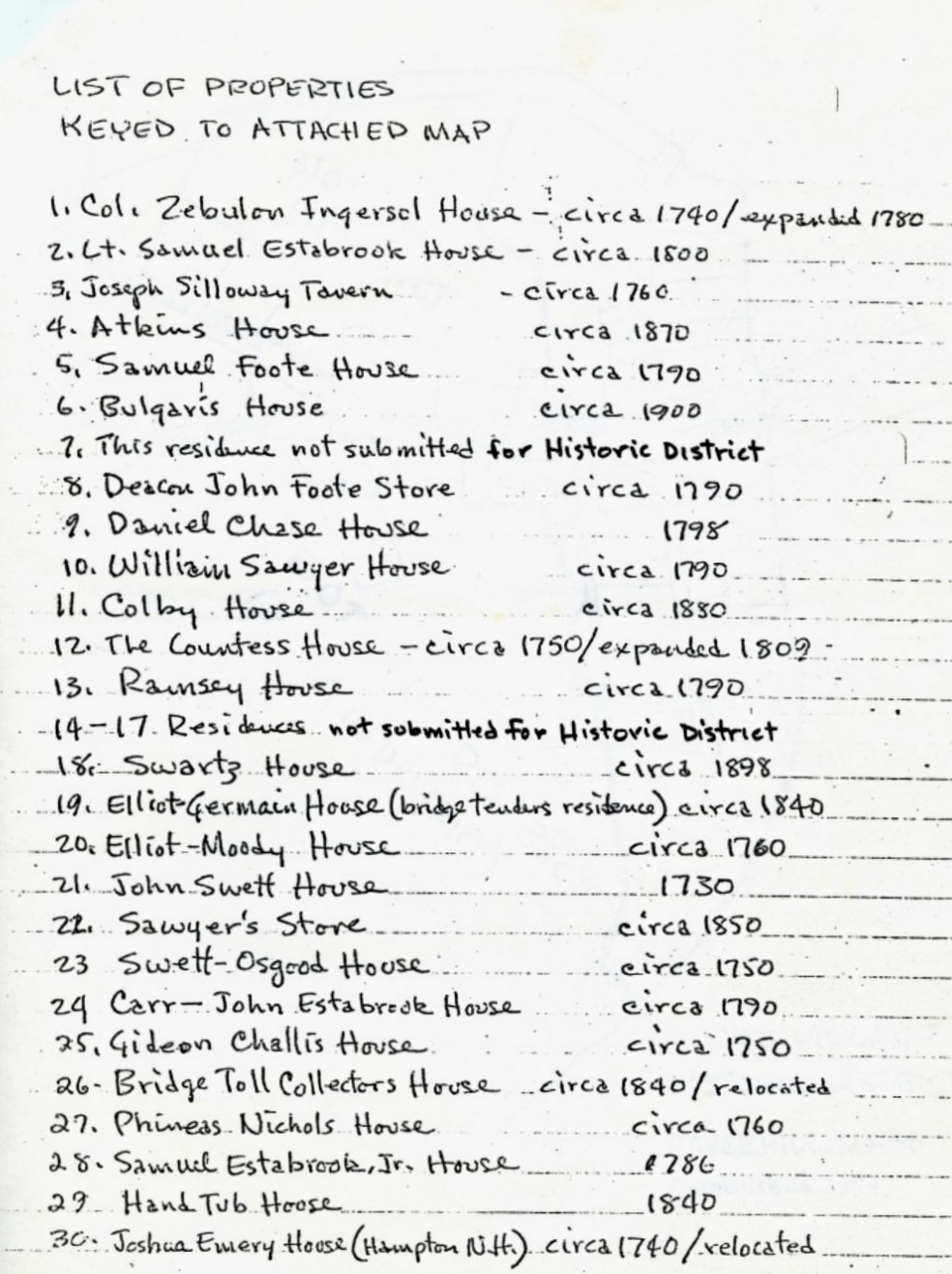

Here are two documents identifying

the location of the property Dolly purchased at 1 Wharf Lane,

next to Historic Rocks Bridge,

surrounded by land, and overlooking

the Merrimack River.

It must have been quite wonderful.

Her brother, Zebulon, who purchased the property from her after Enoch’s death, is listed at the top of the

property identifications.

And below, curtesy of Google Earth,

the present day location.

But this has to be my most fascinating find and potentially revealing material with which to compose Dolly’s story.

HER GRAVESTONE

Here are all three – first Mary Stone, then Enoch Greenleaf and finally Dolly Ingersoll –

the text on each is transcribed below with, most remarkably, a poem, barely legible, on Dolly’s stone.

Sacred

to the memory

of

Mrs. Mary Greenleaf

wife of

Mr. Enoch Greenleaf

who departed this life

Feb. 9, 1789

In Memory of

Capt.

Enoch Greenleaf

who died on Jan. 9, 1799

in the 41st year of

his life.

In memory of

Dolly

wife of

Enoch Greenleaf

Ob. April 17, 1816

AG 59

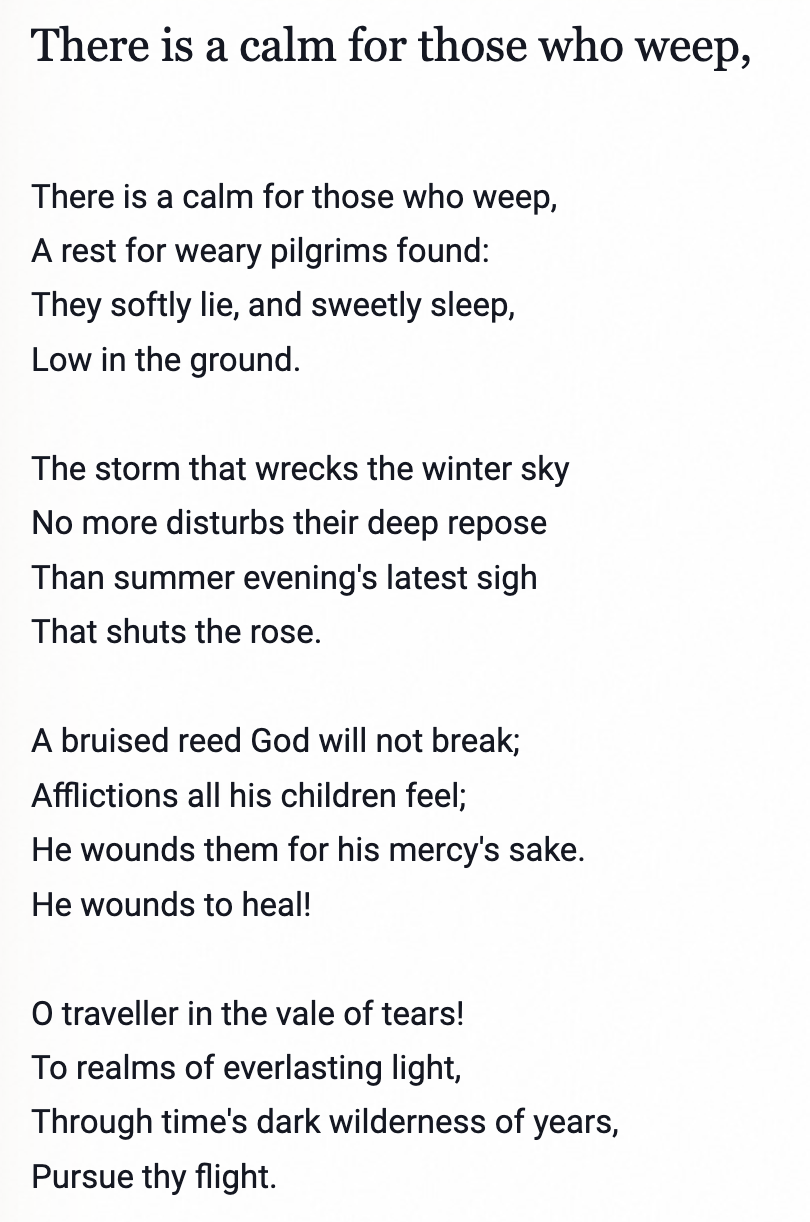

There is a calm for those who weep

A rest for weary pilgrims found

And while their mould ring ashes sleep

Low in the ground…

Notice that Dolly’s age for her death is inscribed as 59, yet we know that she was born in 1755, which would have made her 61. My guess is that for vanity’s sake she may have told her children, who may have had a say in the details of her stone, that she was the same age as their father who was born in 1757.

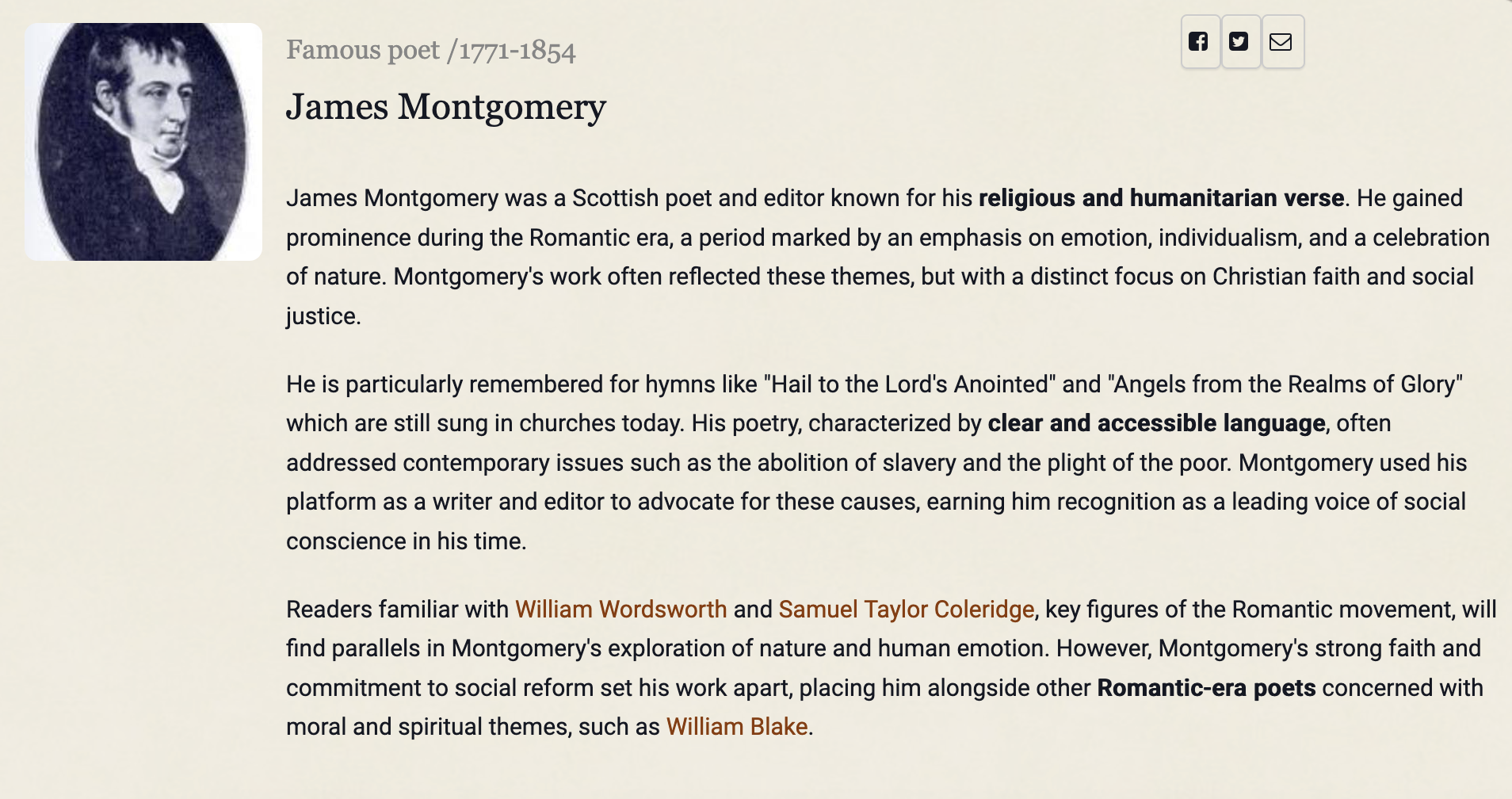

But much more interesting is the poem on Dolly’s stone – which though difficult to make out appears to say what I’ve transcribed above. Hoping for clarity I googled the poem and not only discovered its author – James Montgomery, 1771 – 1854, I discovered that one of the lines had been changed from something lovely to a rather ominous image. Where the actual third line in Montgomery’s poem reads: “They softly lie and sweetly sleep”, on Dolly’s stone the 3rd line reads: “And while their mould ring ashes sleep”. You can see the full poem below along with a brief biography of the poet.

I’m possessed to know who chose this poem for her gravestone and who changed the words. Was it a popular poem at the time for headstones or does the choice tell us more about the person who chose it? It just occurred to me that Dolly might have chosen it herself, and in some stroke of darkness changed that third line. And if she did choose this poem, it certainly adds to the complexity of her character – adding a depth which may on surface merely seem impulsive, erratic and self-centred – especially when you consider the third stanza:

A bruised reed God will not break;

Afflictions all his children feel;

He wounds them for his mercy’s sake.

He wounds to heal.

And there is more – literally. There are more words below the poem. Could they be more of the poem or something else? It’s not possible to tell from the photo as the words are hidden behind grass. It’s also possible that even more words have sunken into the earth. I’ll simply have to go to Newburyport and see for myself.

Her children with Enoch would have been 16, 14 and 11 when she died. Did they know that they had two half brothers? Did they ever visit their Uncle Nathaniel in Maine – just six miles from Gray? Did Joseph know that she died? Did he ever visit her grave with their sons? They would have been 15 and 12 when she died.

Hoping to learn more from Dolly’s children I followed each of their lineages right up to the 21st century where all 3 lines go dead. Questioning FamilySearch.com about these abrupt endings I learned that no information is given about people who are still alive. So that gives me hope of possibly finding at least one of them.

I’ve also recently learned that Dolly and Enoch’s son George and the husband of their daughter Dorothy were silversmiths and that Dorothy and husband settled in Portland, Maine where their son became a jeweller and watchmaker. Because of Portland’s close proximity to New Gloucester where both of Dorothy’s uncles lived – her maternal uncle Nathaniel Ingersoll and her paternal uncle Moses Greenleaf, and equally close to the Cummings farm in Gray, I’m quite certain now that they not only would Dorothy have known about her half brothers, but very well might have known them.

All in all I continue to be enchanted by this woman – Dolly Ingersoll – who for so many years had been no more to Mom and me than a name – just another Cummings wife. But here she is – having completely captured my imagination – motivating me to unearth this wealth of material and then weave it into a story that just might possess a grain of truth.

But before we leave Dolly – and once again – a debt of gratitude must be paid to her, for the simple reason that no matter how unfathomable her actions appear to us today – no matter how reckless, unstable or merely desperate she seems to have been – without her and her choices our ancestor Isaac Jennings Cummings would never have existed to marry our Mayflower ancestor, Lovina Caldwell, and produce Albert Webster Cummings to whose story we now turn.

Links to both Albert’s story and my fictionalised account of Dolly’s life soon to follow.

Your comments are welcome (especially if you have any theories about Dolly 🙂

Please contact me at [email protected]