The MAD MINDS of our COLONIAL ANCESTORS

Please view on full-screen monitor or laptop.

APOLOGIES: This page was initially titled The Puritans for those who settled the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. This colony was my focus because when Mom and I began our research in the 1970’s we thought that it was the only colony to which our first ancestors immigrated from England: We thought that John Bishop immigrated in 1628 and that Isaac Cummings followed in 1630. But as my page – “Research Surprises” – has painstakingly demonstrated, we were wrong!

Through the remarkable site – FamilyResearch.org – I discovered that only Isaac Cummings was a member of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and that he only arrived in 1635. Another surprise was the degree to which our Cummings ancestors were involved in the Salem Witch Trials. And an even bigger surprise was that our Bishop ancestors were never even in New England. John Bishop immigrated to the Jamestown Colony in Virginia in 1638 with a land grant from the Crown to establish a tobacco plantation. But the biggest surprise of all was that we do indeed have Mayflower ancestors – 12 in all. And 10 of them survived that first horrific winter to thrive for many generations in Plymouth Colony.

So amazingly, our ancestors come from not one, but all three of the first significant British colonies in America. And this has meant that my historical introduction to what was only supposed to be one colony, has had to get a whole lot longer. So long in fact that our Mayflower history now requires its own story – especially due to the sheer volume of detailed information we have about each one of these ancestors.

And so this page will focus on only two of the colonies – Jamestown, the home of our first Bishop ancestors, and Massachusetts Bay, home to our first Cummings ancestors. I’ll share the radically different reasons each colony was settled, as well as the small parts each of our early ancestors played in their development.

But be forewarned: This is a very LONG page. I could not help myself. I was so fascinated and entertained by all that I learned that I couldn’t leave anything out. But I’ve done my best to fill it with as much hilarity as these two, often absurd, colonial mindsets deserve. And SO I do hope you’ll give it a go – maybe with a strong cup of joe – and early in the mo. There are Two Easter Eggs waiting for you, if you do!

JAMESTOWN – THE FIRST BRITISH COLONY

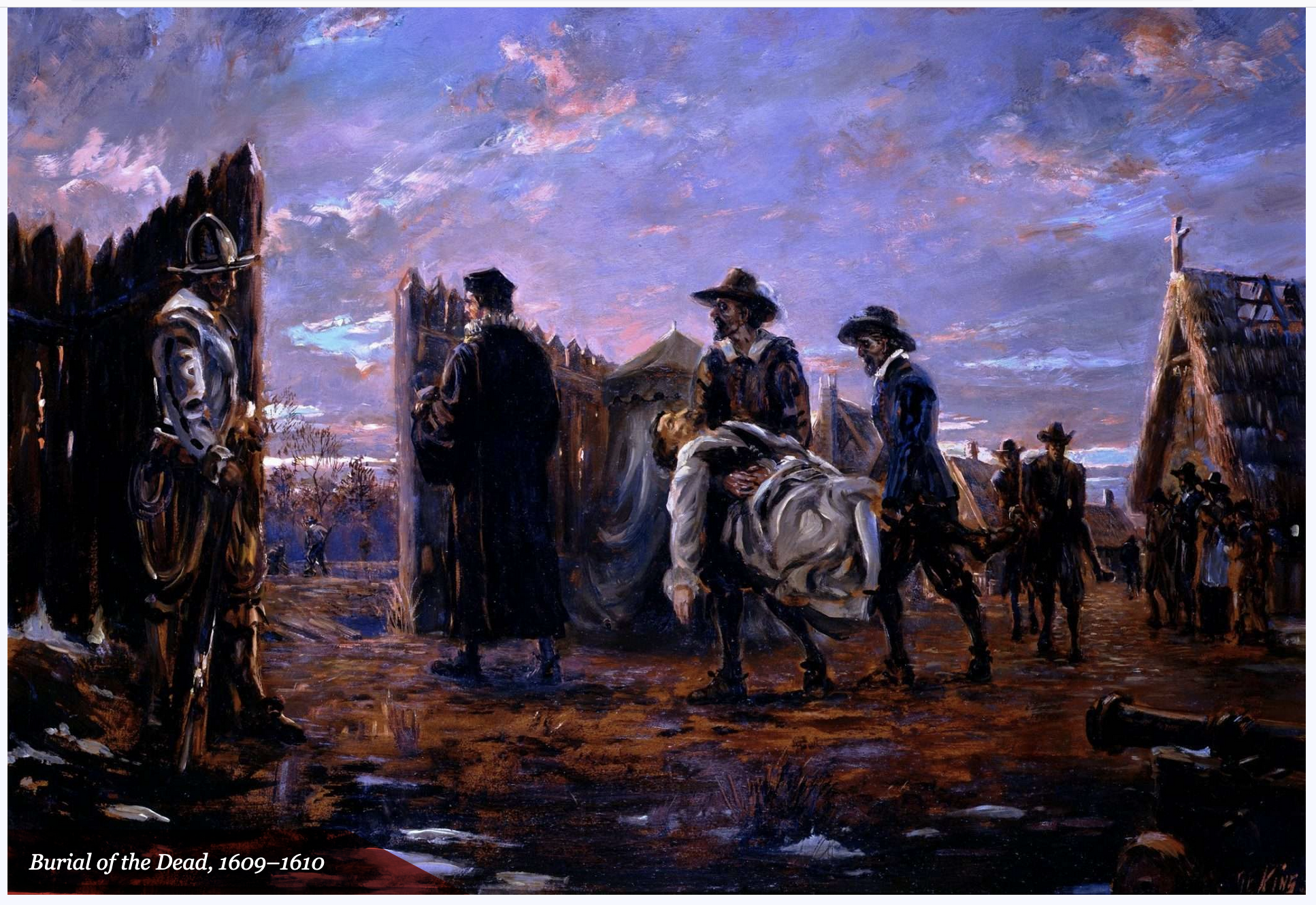

Jamestown was founded in Virginia by the British Crown in 1607 as both a moneymaking venture and a means to establish a political foothold in the New World for England – which was being rapidly outpaced by Spain and France. Two previous colonies had already failed, and while Jamestown eventually succeeded, it got off to a horrifically rocky start. The Crown offered land grants to second and third sons of noblemen who had no chance of inheriting land in England. And they brought with them indentured servants – whom they expected to do the work of setting up the colony while they scouted at their leisure for gold. (The Spanish had found gold in South America, so they presumed without even a shred of evidence that they would find it in Virginia as well.) It was a recipe for disaster.

Neither the noblemen nor the servants had even the most basic skills necessary for surviving in this hot and humid climate where diseases were easily transmitted through hoards of insects. Nor did they have farming skills for this unfamiliar terrain, nor the diplomatic or even military skills to deal with the less than welcoming indigenous population. The Crown, however. anxious for financial return, repeatedly sent supplies and new settlers – despite there being no gold, a lack of any real farming success, and reports of high death rates from disease, starvation and violent interactions with the local native tribe.

Only in 1612 when John Rolfe brought sweet and mild tobacco seed from the West Indies – highly sought after in the UK – did this crop begin to generate real profits. And then, with the introduction of slave labour from Africa in 1619, Jamestown as a financial success took off.

Jamestown Colony, holds special significance in our family stories because Stephen Hopkins – one of our Mayflower Ancestors – lived there from 1610-1613 as part of a resupply mission in the earliest years of the fledgling colony. And during those years he would gain invaluable survival and negotiating skills that would contribute greatly in overcoming challenges during both the Mayflower crossing and in setting up Plymouth Colony. The Mayflower stories will explore his now infamous and entertaining exploits.

Jamestown is also significant to us because our first Bishop ancestor – John – settled there in 1638 with a land grant from the British Crown to establish a Tobacco Plantation.

Charles City, the site of the Bishop plantation, still exists today, just northwest of Historic Jamestown. Bishop lived there with his family until his death in 1658 and during those years represented Charles City in The House of Burgess – the first representational legislative body in British America. This governing body was established in 1619 – the same year African slaves were introduced to work the tobacco fields. So it is no small irony that the seeds of democracy and slavery each had their beginnings in America at the same time and in the same place.

Jamestown is often considered the birthplace of Democracy. But Plymouth Colony will mount a strong contest for this position – which we’ll explore in the Mayflower stories. However, because Jamestown instituted America’s first representational government and because Virginia would later birth Thomas Jefferson – author of the Declaration of Independence – as well as George Washington – America’s Daddy, Jamestown continues to make this claim. A more accurate account is that the House of Burgess was anything but democratic. Jamestown, with its Crown charter, was under the strict control of King James, who only granted land to English noblemen – who were consequently the only ones who could vote or hold office. So when years later the Burgesses began to move against the Crown it was for the simple reason that that they wanted to call the shots. And they definitely didn’t want to be paying the high taxes the king was demanding. But they had no intention whatsoever of giving up the political power they enjoyed.

Class consciousness certainly existed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony as well, but never to the degree that it did in Jamestown. And the main reason for this was simple demographics. Over four-fifths of the Boston population was middle class – made up of literate small business owners and skilled farmers and craftsmen, who had come to the colony with their families, along with clear plans for the kind of community they wanted to create.

In sharp contrast, most of the population in Jamestown was made up of unskilled labourers – young uneducated single men, hoping to escape dire poverty and often prison in England, through the lesser evil of indentured servitude. But their living conditions were so deplorable that most of them died before they could serve out their seven years and receive the money and land they’d been promised. So these men clearly had no political voice, just as the African slaves who would replace them.

These demographic differences between the Northern and Southern Colonies would continue for generations. And in many ways debates over who is best suited to govern – a self-appointed elite or the general population – is alive and well in today’s politics. And this takes us directly to the Puritans and the Massachusetts Bay Colony – settled in 1630 – and their even more confusing ideas about governance and leadership.

THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY COLONY

And the Puritans who settled it.

Important clarification before exploring this colony: There were two distinct groups of Puritans – the Separatists and the Non-Separatists. The Separatists wanted quite simply to separate completely from the Church of England. Their strong opposition to both the Church and the Crown made England unsafe for them and so they escaped to Holland in 1608. And then when even liberal Holland became unsafe they left for America, traveling on the Mayflower in 1620, and settling the small colony of Plymouth. Our Mayflower ancestors come from this group of Puritans and we’ll learn more about them in Our Mayflower Story.

The Non-Separatists wanted to remain a part of the Church, but they wanted to reform it, while still remaining loyal to the Crown – which begrudgingly tolerated them. But with increasing political instability in England these Puritans also came under threat and so decided they could better reform the Church from the other side of the ocean, and so began a massive immigration in 1630 to the Massachusetts Bay Colony under the leadership of John Winthrop. This is the colony to which our Cummings ancestors came. And it is their story we’ll now explore.

The Puritans were followers of John Calvin – born in France in 1609. A trained humanist, he broke from the Roman Catholic church in 1536 and fled to Switzerland. There he joined the Protestant Reformation, which wanted to do away with both the hierarchical power and the pomp and circumstance of the Catholic Church in order to return to what was considered a purer form of Christ’s teachings. Among the many beliefs held by the Calvinists, two of them had a particularly powerful impact on these early New England settlers. The first belief seemed admirable enough – that we each have the ability to communicate directly with God and do not need either clergy or a head of state to intervene for us. This belief was most certainly grounded in the 15th century invention of the printing press, which made the Bible available to any one who could read – and which naturally lead to the wide-spread value of literacy among the Calvinists. The second belief was that of Providence – that we are each predestined to go to either Heaven or Hell and that there is nothing we can do in our earthy life to change this.

Is it just me or do these two beliefs seem just a tiny bit incompatible? Even the concept of Providence on its own seems to contain a rather mind-boggling Catch 22: Why bother to behave well here on Earth if where you go when you die is completely out of your control?

But fear not… the Calvinists had a clever work-around. If you were one of God’s chosen you wouldn’t want to behave badly. Therefore your good behaviour was evidence that you were indeed one of God’s chosen. At the same time ANY behavioural slip-up was proof you were not one of his chosen. My guess is that the question of who would decide what was good or bad behaviour was at the heart of this issue. For despite the purported goal of Calvinism to more closely adhere to the original teachings of Jesus, compassion and forgiveness didn’t seem to be a high priority.

If anything these Reformers seemed to resonate far more with the punitive hell, fire and brimstone nature of the Old Testament, than to any of Jesus’s teachings. And this further suggests that the purported desire of these Calvinists to dispense with hierarchical authority, didn’t apply when it came to local civil governance. In this domain social control, meaning strict conformity among adherents, was precisely what they were after – and markedly so among these Boston Puritans.

PURITANS IN THE NEW WORLD

Because Puritans believed that everyone could communicate directly with God no formal churches were required. Instead worshipers would gather in private homes or even – as depicted here – under a tent. Or not at all. Such was the belief that one’s relationship with God was a private matter, not a public one. This lack of formality along with the freedom to worship as one chose worked especially well as long as the Puritans were living in England – for the simple reason that they had to worship in hiding anyway. But once the Puritans arrived to the New World where they could worship openly another all important issue came to the forefront.

In England they had lived under British law and while mostly unfavourable to them, it was at least clear what they could and could not do. But in the New World they now had to establish their own form of government and their own set of laws and codes of behaviour.

Moreover they had moved to a hostile territory where cooperation was of utmost importance for their very survival. So pretty quickly the concept of freedom to worship as one chose became far less important than social cohesion and conformity to a clearly defined set of behaviours. Moreover the question of who would determine what was good or bad behaviour became for the first time a political one. As a result, a great deal of personal freedom more or less flew out the window. And one of the first freedoms to go was the issue of church attendance. Non-attendance quickly became equated with evidence of not being one of God’s chosen. And worse, it was met with severe public shaming and even physical punishment.

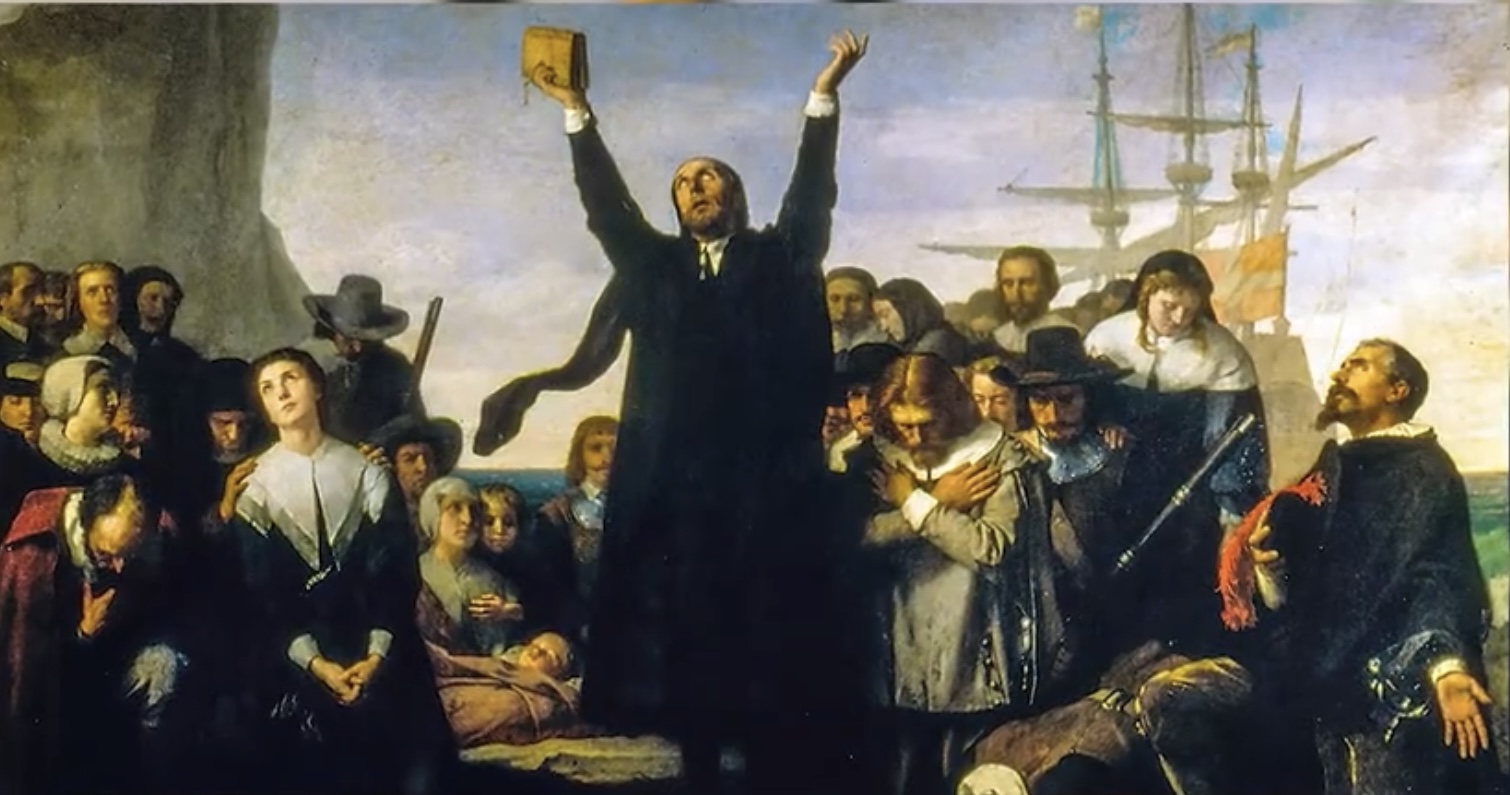

Here is an idealised depiction of John Winthrop delivering his famous “Shining City on a Hill” sermon upon the arrival of his ship the Arabella to Boston Harbon on June 12, 1630. The theme of this sermon expressed the Non-Separatist intention of becoming a model of the reforms they wanted to see in the Church of England – in particular the granting to each individual the right to communicate directly with God without the interference of King or clergy. But we’ll now learn more about the less savoury contents of Winthrop’s sermon when it came to the matter of establishing the social order for the new colony and, in particular, who would be in charge.

SO, WHO’S GOING TO BE IN CHARGE?

A great deal is revealed in Winthrop’s journals which begin with that first sermon in 1630, upon his arrival to the New World. And while this sermon expressed a requisite amount of Christian brotherly concern, the underlying message was clear:

“The rich and mighty should not eat up the poor” and the “poor and despised” may not “rise up against their superiors and cast off their yoke.

So while the value of New Testament brotherly love may have been the ultimate idealised goal for Winthrop’s “Shining City on a Hill”, the means for achieving it was clearly more closely aligned with the hell, fire and brimstone nature of the Old Testament .

And it is into this world that our first Cummings ancestor, Isaac, would arrive in 1635 and our last Cummings ancestor would flee when Albert Webster moved to Minnesota in the mid 19th century. Here’s a Cummings descendant cavorting with a known Catholic heretic. Anybody recognise them?

And now for some demographics on who was “superior” and who was “poor and despised” among the Puritans

The first settlers to the Massachusetts Bay Colony were composed of the following: 10% servants and 10% unskilled labourers. So Winthrop’s “poor and despised” were this 20% whom – to his mind – possessed neither the education nor the motivation to aspire towards heavenly grace and were therefore in dire need of a strong hand to keep them in line – whilst being treated just well enough to quell any desire to rise up against their betters.

These “betters” – the remaining 80% fell into two distinct groups: 79% were what we’d today call the middle class – skilled craftsmen, small businessmen and farmers. And the other 1% came mostly from the second and third sons of noblemen who had no hope of inheriting land or positions of authority in England. But they could easily achieve both in the New World – through their social status and often substantial material wealth. This 1% could easily convince the 79% that they were most qualified to govern – while at the same time holding out a carrot stick of the possibility of attaining both wealth and authority – and many of them would – but only by first bending to the will of this best of the betters – the 1%. For the key ingredient which the 1% and the 79% shared – the great leveller – which the 20% did not share – was literacy. They could read and write. And so it is to the significance of literacy that we will now turn.

The Importance of Education to the Puritans.

Education had long been of high value among Puritans and the majority of those who first came to the colonies had been formally educated in England. The primary motivation for literacy was to be able to read the Bible, but the benefits of such skills to these colonists was equally fundamental in their ability to organise themselves, and work cooperatively to set up a functioning government and economy. So it’s of little surprise that in 1636 – a mere 6 years after the arrival of the Puritans to Boston – that Harvard University was founded.

This was in sharp contrast to the majority of immigrants to the southern colonies – most of whom were poor and illiterate. Most had come as indentured servants and would often die from disease and overwork long before they could receive the freedom and plot of land promised to them for their seven years of hard labor. Certainly no attempt was ever made to educate these immigrants just as education would be denied to the black slaves who followed them. It was only when Southern land owners began seeing how financially successful the northern colonists were becoming that they began educating their own children – sending them to institutions of higher learning in the North and eventually establishing their own. William and Mary was only founded in Williamsburg, Virginia in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III and Queen Mary II – nearly 60 years after Harvard.

Ironically literacy would be instrumental in both the early success of the Puritan colonies, as well their ultimate decline, for the simple reason that you cannot teach people to read and then expect them not to think. And think critically they did, so it wasn’t long before serious rifts among the Puritans began to form.

One such critical thinker was Separatist minister Roger Williams

Newly arrived to Boston in 1631 and unhappy with what he saw he quickly fell into disfavour with the governing court. He left for the Separatist colony of Plymouth, but found them to be equally narrow-minded and self-serving. He insisted that colonists should pay native Americans for the lands they’d taken from them – a concept distasteful to most colonists who’d convinced themselves that God wanted these lands for them. Nonetheless he gained such a strong following that in 1636 – the very year, ironically, that Harvard was established, the General Court banished him. Unthwarted he left with a substantial following and founded Providence Plantation in what would later become Rhode Island. There he purchased land from the local indigenous tribe and, learning their language, created good relations with them. He then set up a government separate from the Church and welcomed people of all races and faiths. Fun discovery: the 1660 immigration of Tristram & Anne Dodge – direct ancestors of Don & Dick and the first settlers to Rhode Island’s Block Island.

Anne Hutchinson was another critic of the court. A highly literate and well respected member of the community she began holding weekly meetings in her home to review the previous week’s church sermon. These meetings became extremely popular and gave people a chance to express their criticisms of some of the more irrationally strict codes of conduct for the community. They began to oppose the edicts of the General Court – especially that only members of the elect could serve on it and, of course, that only the Court could determine who qualified as the elect.

Anne went so far as to challenge the edict that only men could serve on the court and so she too was banished. She would initially settle with her followers in Rhode Island with Roger Williams but later moved to what is now the Bronx, NY, when even Rhode Island came under threat from Boston. And there she was sadly killed, caught in the Kieft’s War between local settlers and the Siwanoy tribe. Of course the General Court took this as evidence of God’s wrath upon her for challenging the established norms.

Both Williams and Hutchinson represent the birth of religious tolerance in America. They both believed that man is his own path to god. And Williams in particular believed that each man finds his path in different ways: the Natives, the Jews, the Muslims, etc. So he invited everyone to come no matter their religion, thereby becoming a model for other colonies. Other groups began breaking away from the General Court, and by the end of the 17th century ardent Puritanism had begun to die out – with the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 dealing its final blow.

More than a century later Jefferson would base his doctrine of separation of Church and State on the ideals of Roger Williams. But sadly, few of our Cummings ancestors exhibited any of these admirable qualities until long after the horrors of the Salem Witch Trials, when one of our Mayflower descendants – Lovina Caldwell – married Isaac Jennings Cummings and gave birth to Lola’s grandfather, Albert Webster Cummings, whose Methodist ministry echoed so many of Roger Williams values.

Likewise, Jefferson might have paid greater attention to Williams treatment of America’s indigenous tribes, who had in so many ways helped the earliest colonial settlers survive at all, and in exchange for so very little, only to eventually be driven from nearly all of their lands and massacred nearly out of existence. I’ll more fully explore the relationship between the indigenous population and the Puritans in OUR MAYFLOWER STORY, where I’ll share both detailed stories about their interactions, as well as the mental gymnastics employed by so many Puritans to justify their often barbarous treatment of these native tribes. And this kinda leads us directly to . . .

The Puritan Economy

For in the same way that the Puritans had to do some serious cerebral acrobatics to justify their habitual slaughtering of the indigenous population, so were they equally successful in readjusting their values from the spiritual to the material as their financial successes grew. Understanding what brought about such enormous successes is both complex and fascinating. On the one hand the Puritan work ethic – an idle hand is the devil’s playground – provided a firm base for their success. And adding to that was the Puritan aversion to ostentatious displays of wealth. Remember they’d left both the Catholic church and then the even the Church of England in opposition to the opulence – the pomp and circumstance of both. So when the Puritan settlers began making profits, but were unable to allow themselves luxuries, they did what any reasonable Puritan would do… they reinvested their profits, leading to an ever-increasing accumulation of wealth. And just as good behaviour had become for the Puritan’s proof of being one of God’s chosen, so financial success likewise came to be considered at minimum proof of His approval.

But perhaps the greatest contributing factor to the settlements’ tremendous financial growth was the confluence of the poor quality of New England soil – too poor for anything but the most basic foodstuffs – at the same time that the global economy was disassociating wealth from land ownership, resulting from the rapid expansion of European exploration and the trade of goods. So as a matter of survival the Puritans had to enlist their well-educated ingenuity towards other means of creating income. And as many of these first settlers were already skilled craftsmen and experienced entrepreneurs, in addition to being literate, hard-working and good at accumulating and reinvesting capital, it wasn’t long before New England became the centre of America’s fast-growing industrial economy.

It cannot however be understated the wealth of resources these clever and hard working colonists had to work with – the lucrative beaver skin trade, fishing and the timber from vast hard wood forests. Timber was initially used to build almost everything the colonists needed and was also marketed in the UK and the West Indies. But the real wealth came from ship building, followed by the cycle of international trade of both goods and slaves – between the northern colonies, England, Europe, Africa and the southern colonies. For while slavery was generally looked down upon in the northern colonies, making money from carrying them from Africa to the southern colonies was not.

For Your Amusement

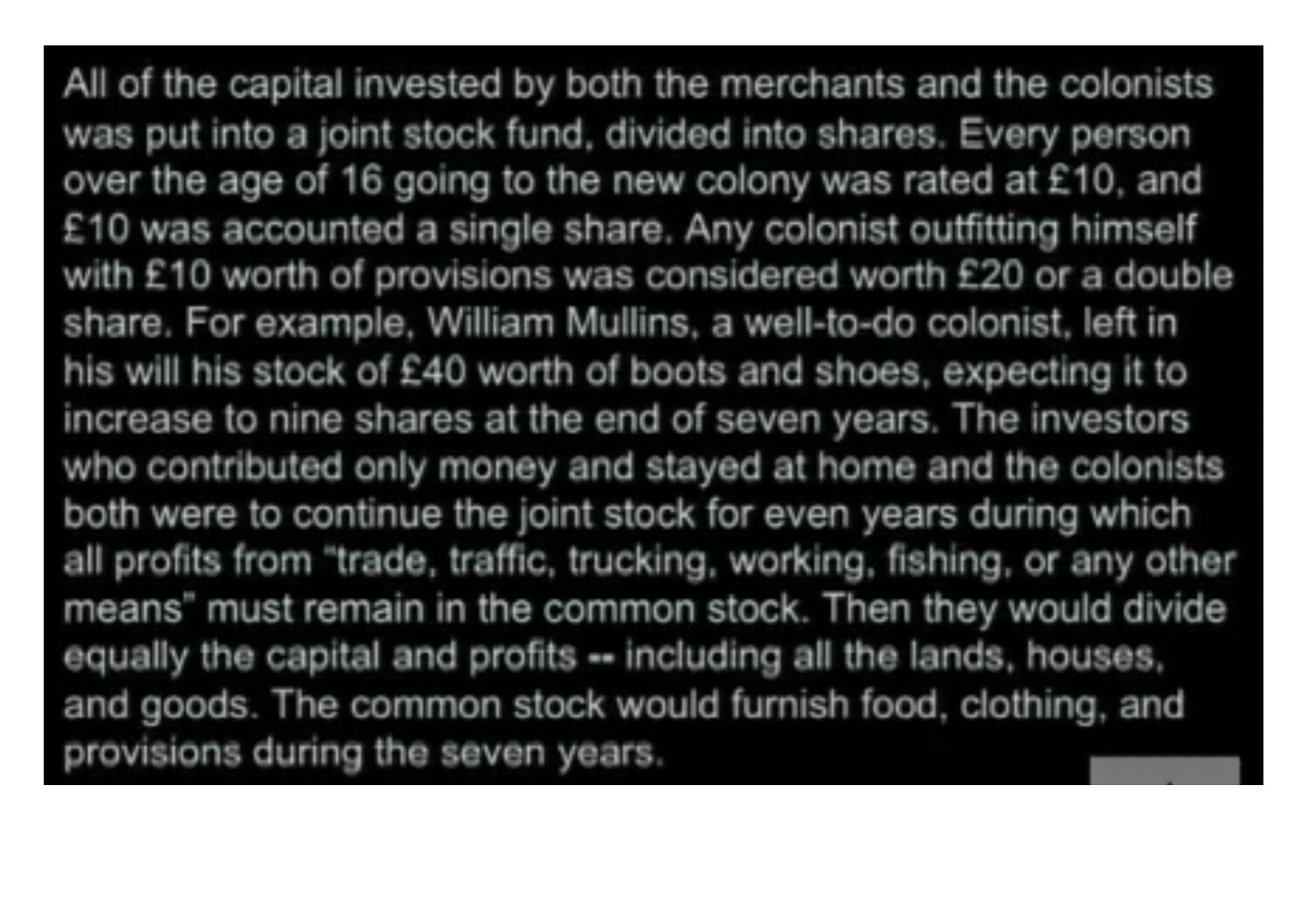

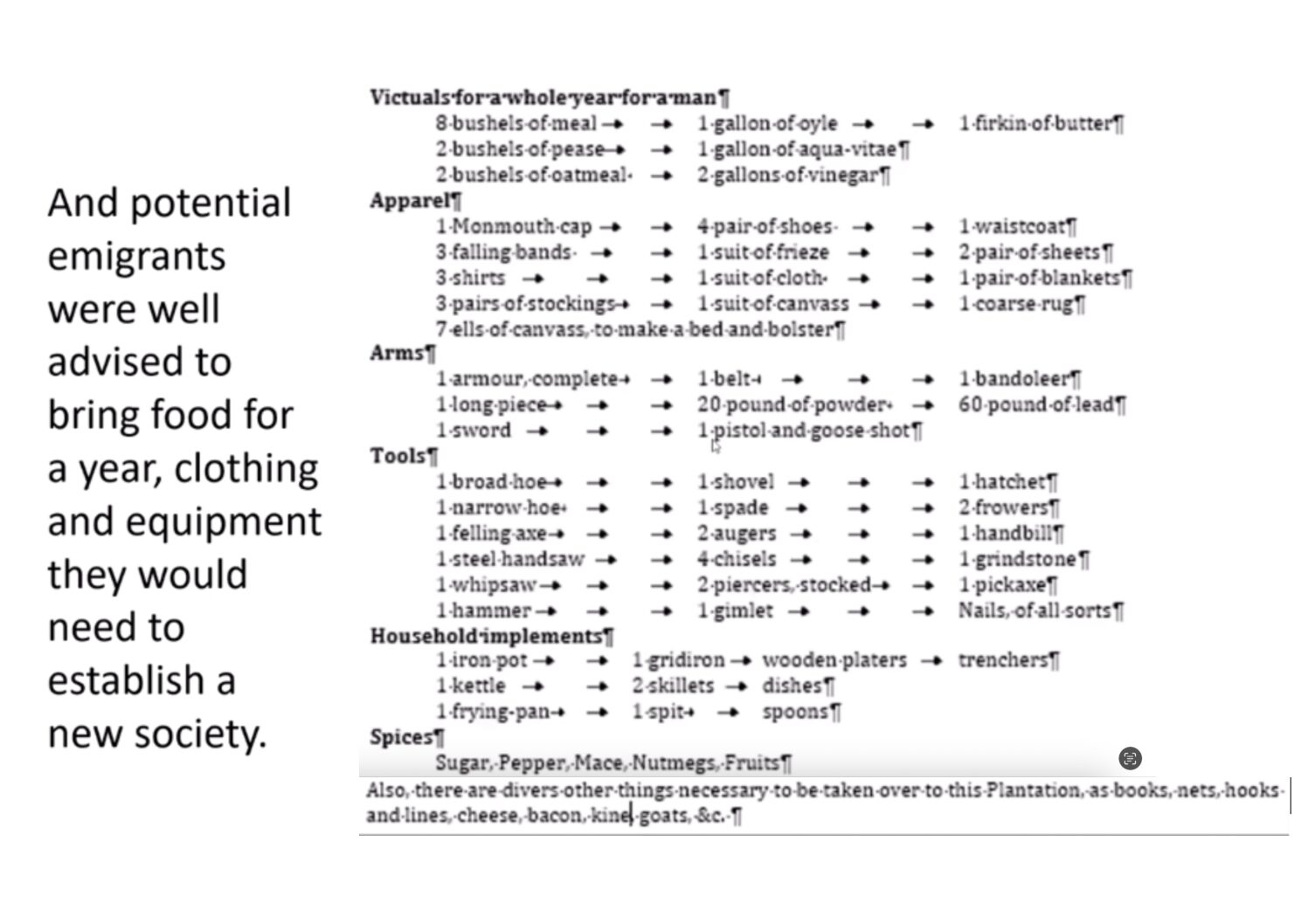

To get some sense of the minds at work in getting the first colonies off the ground, here are two documents – the first of which describes a common joint-stock contract necessary for establishing a colony, and the second details the extensive list of items the settlers were expected to bring with them in order to survive the first year – a list the Jamestown settlers would have done well to possess.

It’s especially fun to note that the joint-stock contract described below is quite possibly the one created for the Mayflower passengers’ plan to settle the Hudson Bay Colony. For it includes the name – William Mullins – one of our Mayflower ancestors.

Here is my transcription of this hard to read description of the joint-stock contract:

All of the Capital invested by both the merchants and the colonists was put into a joint stock fund, divided into shares. Every person over the age of 16 going to the new colony was rated at 10 pounds, and 10 pounds was accounted a single share. Any colonist outfitting himself with 10 pounds worth of provisions was considered worth 20 pounds or a double share. For example, William Mullins, a well-to-do colonist, left in his will his stock of 40 pounds worth of boots and shoes, expecting it to increase to nine shares at the end of seven years. The investors who contributed only money and stayed at home and the colonists both were to continue the joint stock for even years during which all profits from “trade, traffic, trucking, working, fishing, or any other means” must remain in the common stock. Then they would divide equally the capital and profits – including all the lands, houses and goods. The common stock would furnish food clothing, and provisions during seven years.

And here is the magnificently entertaining recommended settlers’ supply list – well worth every bit of space it’s taking up. But I’m not sure if it was intended for the Mayflower immigrants or those who traveled in Winthrop’s Fleet to the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

And finally, a Shout-Out

to Anne Bradstreet

the First American Female Poet

Anne was born in 1612 in England and came to Boston in 1630 with her parents and young husband. A well to do family they sailed on the Arbella with John Winthrop – the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Both her father and husband would each later become governors. And the two of them would also be instrumental in founding Harvard University in 1636 – the first institution of higher learning in America.

Anne had been well-educated in England and – despite giving birth to and raising eight children – she developed an early passion for composing poetry. But it was a passion she had to downplay.

It’s important to remember that the Puritans frowned on nearly any kind of pleasure – so much so that at one point the High Court had the Psalms re-written in plainer language, because they were considered too poetic. So it was quite a feat for Ann to write at all, let alone in such a way that she would not further ruffle any feathers. Therefore much of the content of her work was in high praise of God and her gratitude for her subservient position as wife and mother. But within her work there was no shortage of thinly disguised ironic messages which on surface appeared to support the notion that a woman’s role was better served with a needle in hand than a pen – while demonstrating with the sophisticated complexity of her poetry her obvious intelligence and talent.

We can thank her brother-in-law who – recognising her extraordinary talent, but unbeknownst to her – took a collection of her poems to London and had them published. They were highly received in London almost immediately, and not long after in the colonies. So before her death she would gain the distinction of being the first published female poet in America.

By the time Anne Bradstreet died in 1672, all those who wanted a freer and more compassionate life than the General Court would allow had left. While those who remained succumbed to greater and greater restrictions. Winthrop’s dream that they would create a “shining city on a hill” never materialised and those who remained seemed to clutch ever more fervently to the Old Testament hell, fire and brimstone interpretation of the Bible – making them ripe for the horrors of the Salem Witch Trails to come. And when we explore the trials we’ll have to face the shame regarding the roles some of our Cummings ancestors played in them. But we can also witness a kind of redemption through the blending of the Cummings line with that of Mary Towne Easty’s, which will explore with Mary’s story and her role in the trials.

But before we turn to the trials we need to complete our exploration of the three British colonies we are heir to by looking at our connection to the Mayflower passengers and the Plymouth Colony they created.

Link here to “Our Mayflower Ancestors”

Your comments are welcome. Please contact me at [email protected]