OUR MAYFLOWER ANCESTORS

From early childhood I’d been told that our family came to America seven years after the Mayflower. It was a fun fact, like this cartoon image, that I never questioned. Even in my mid-twenties, when Mom and I began our research, neither of us questioned it because it fit with the dates Bud Harvey, our Bishop cousin, had provided us: Richard Bishop arrived in Salem in 1628 and Isaac Cummings arrived to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. So the Mayflower and Plymouth Colony were never on our radar, since neither Bishop nor Cummings were ever in Plymouth. Of course I then discovered that John Bishop, not Richard, went to Jamestown, not Salem, and Isaac only arrived in MBC in 1635. Still Plymouth Colony continued to be ignored.

Then by chance…

. . . just as my curiosity about how the Bishops ended up in New York – leading to the surprising discovery that they weren’t Puritans at all but the owners of a Virginia tobacco plantation – so my curiosity over why our Cummings ancestors moved from the relative safety of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to the wilds of Maine led me to the even more astonishing discovery that we are indeed descendants of not one but several Mayflower passengers whose descendants would go on to live for several generations in Plymouth Colony.

And like a good many of my most fascinating discoveries, this new found connection to Plymouth Colony came once again from Following the Women! I had first followed the paternal line of Albert Webster Cummings – the Methodist minister and great, great grandfather to Don, Dick and me – all the way back to our first Cummings ancestor, Isaac, who joined the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635. And that path took me through our close involvement in the devastating Salem Witch Trails (another surprising discovery), but it didn’t tell me why the Cummings moved to Maine, only that they did. And so I turned to Albert’s maternal line – his mother Lovina Caldwell – hoping for a clue. And to my amazement I found that her lineage took me directly back to the Mayflower passengers – and not to just one or even a few, but to 12 of them! And – as with the other surprising discoveries – I have little doubt that my instinct to go down this rabbit hole was our mother Bernice’s doing!

I’d had little more than a school girl’s knowledge of or interest in either the Mayflower or the Plymouth Colony but . . . nothing like discovering that one’s identity is attached to something so historic to suddenly develop a passionate interest in it. Luckily because this history is so fundamental to the American story, there is a wealth of extraordinary detail about every passenger who was on board for this harrowing journey, their experience of the first horrific winter and how the lives of those who survived unfolded.

But before launching into the individual stories of our Mayflower ancestors,

here is a brief summary of how the Mayflower voyage and subsequent Plymouth Colony came to be.

A home in the New World far from the control of the British Crown – that was the original dream of a small group of Puritans known as Separatists – so called because they wanted to separate entirely from the invasive hierarchy of the Church of England. They distinguished themselves from the Non-Separatists who wanted only to reform the Church, but remain a part of it. The latter were mostly tolerated, but the Separatists brought upon themselves such extreme persecution that they were forced to leave England or face imprisonment and likely death. But it was equally risky to try to leave England. Yet after many failed attempts a small group (led by William Brewster and his young protege William Bradford) managed to escape across the channel in 1608 to Holland – a country chosen for its religious tolerance.

Over the next few years more and more Separatists were able to join them and in time they created a community in the small town of Leiden where they managed to live in relative safety for a few more years. But for many it wasn’t an easy life. One of the reasons Holland was so accepting of these refugees was its need for workers in its rapidly growing textile industry. Hours were long and pay was little, so only a few of their community were able to live well. Brewster was able to arrange a position at Leiden University teaching English and others arrived with sufficient means to open small businesses which easily flourished in the growing economy. In time, however, the restrictive beliefs of the Separatists and their penchant for smuggling Separatist literature into England got them into trouble with Dutch authorities who needed the support of King James in their on-going conflicts with Spain. The Separatists also worried that their children were becoming too Dutch – in other words too liberal. So between growing political instability in Holland and their concern over the socialisation of their children the Separatists decided they had to move once again.

They had learned that the Jamestown Colony was succeeding and so chose Hudson Bay (then northern Virginia, now New York) for their new home – hoping to be free there to practice their religion without interference. It was surprisingly easy to get a charter for a colony from King James, who wanted to kill them on British soil but didn’t mind if they helped his mission get a political and economic foothold in the New World. But the next steps weren’t so easy: raising funds for the voyage and finding a sea worthy ship to get them safely across the Atlantic. They eventually found backing with the Merchant Adventurers of London led by Thomas Weston.

Weston purchased the Speedwell, an old ship which would stay with them in the New World, and he rented the Mayflower – a new ship which would carry the overflow of passengers and supplies and then return to England. But unbeknownst to the Separatists the financial agreement involved selling passage to the general public, who weren’t even Puritans, let alone Separatists. They would refer to these passengers as Strangers, and to themselves as Saints. So you can imagine how well they would get along.

They set sail in July of 1620 – already late for such a crossing – with the expectation of arriving by the end of August with just enough time to build shelters plant crops to see them through the winter. But the Speedwell had other plans for them, forcing them back to England for repairs – not once, but twice. The Speedwell – an aging refurbished ship – was so full of hidden structural problems that they would eventually have to abandon it altogether and move its passengers to the Mayflower. And worse, several of the “Saints” had to be left behind to make room for new paying “Strangers” to help recoup their losses. It was bad enough that these Saints had to share the voyage with these godless Strangers, but it was even worse when they all had to fit onto one ship. They were now double what the ship could comfortably hold – forcing everyone to live in agonisingly close quarters with no privacy at all. But the worst was yet to come. Because of the delays caused by the Speedwell they were now only setting off in early September, when they should have already been in the New World. Why they all agreed to go – Strangers, Saints, and Crew – at a time that would seriously risk all of their lives, attests either to their perseverance or wilful ignorance. But had they not made this choice – so ill advised for so many of them – we would not be here today.

The stormy season in the Atlantic was just beginning, regularly subjecting the Mayflower to 100 foot swells and episodes of torrential wind and rain. At one point the main mast cracked and only by extraordinary luck did a passenger have just the tool that could secure the mast for the remainder of the trip. Another near disaster occurred when a young man was blown overboard and only by more extraordinary luck was tossed in the path of a loose rope he could hold onto until the crew realised he was overboard and pull him back onto the ship.

And worse – if anything could have been worse – these storms pulled them so far off course, that when they finally spotted land they discovered that they were 200 miles north of their intended destination. Most everyone was seasick, dehydrated, weak from scurvy and desperate to disembark. But they were also terrified to be in completely foreign territory with no legal right to be there. So they tried to push on to Virginia, only to find that the coastline hid just beneath the waters such treacherous rock outcroppings that one false move would spell disaster. So after a day of agonising deliberation they knew they had no choice but to return to the safety of the bay just inside Cape Cod.

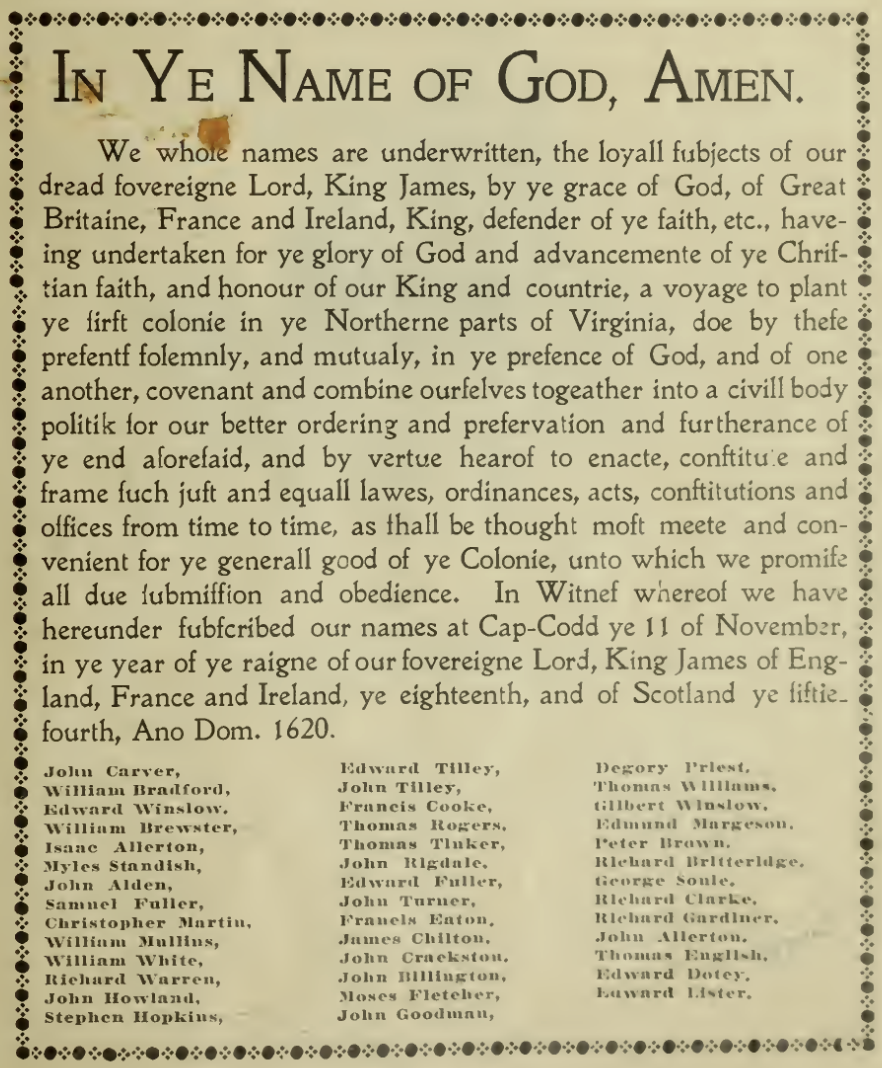

Saints and Strangers Sign the Mayflower Compact and establish Plymouth Colony

They dropped anchor and, even though desperate to leave the ship and look for a safe place to settle, they knew that without a valid charter the colony was at risk of falling into disastrous anarchy – especially with the animus that had been building between the Saints and the Strangers during the torturous voyage. And so they chose to do something remarkable. They created a compact in which they promised to work together, for the good of all – Saints and Strangers alike. And all adult males aboard the Mayflower agreed to sign it before anyone would set foot off of the ship. What is so significant about The Mayflower Compact is that it is the first document to establish self-governance in the New World. And it remained active until Plymouth Colony became a part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691. Forty-one of the adult male passengers of the Mayflower signed the compact. And we are descended from seven of them:

Captain Myles Standish, Stephen Hopkins, Isaac Allerton,

Francis Cooke, William Mullins, and George Soule.

You can find their names on the facsimile of the Compact below. It’s really quite extraordinary.

The language is in many ways so like a prayer that I’ve chosen to transcribe it, using another version

closer to modern English to share with my fellow family descendants.

In the Name of God, Amen.

We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal and our Dread, Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, Etc. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia: Do by these presents, solemnly and mutually in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and furtherance of the Ends aforesaid; And by Virtue, here of So enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony, unto we promise all due Submissions and Obedience. In witness, whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James of England, France and Ireland, the eighteenth and of Scotland, the fifty-fourth, Anna Domimi, 1620.

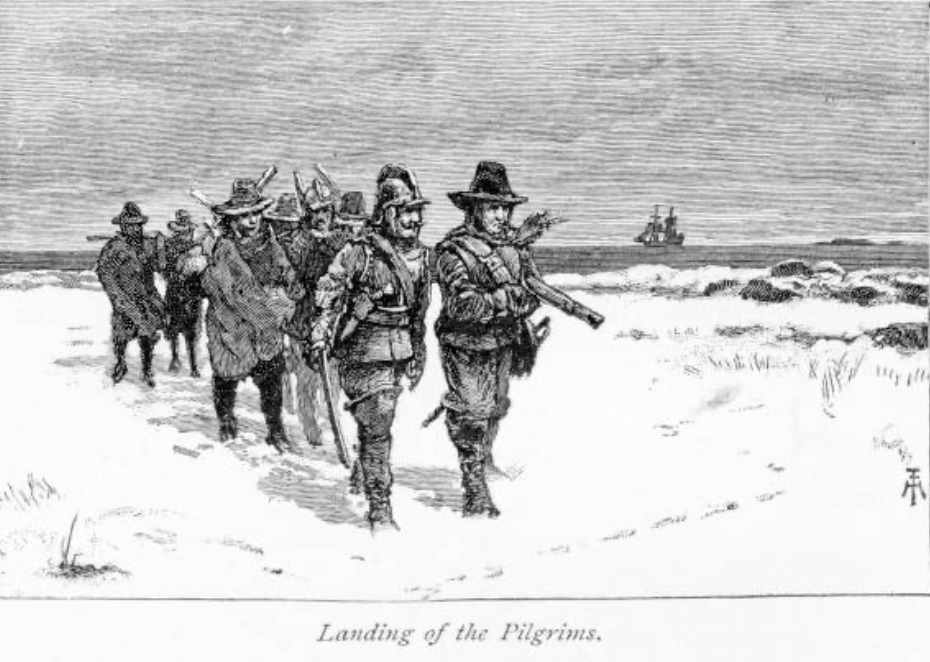

After the signing, and for the next few terrifying weeks, most of the passengers had to remain on board at anchor, in the small bay just off of what is now Provincetown, while the few men strong enough to do so, ventured out to scout the area for a suitable place for them to settle. We know that Myles Standish and Stephen Hopkins were among the scouts. And it took them nearly a month to find a such a place, with fresh water and enough flat open land on which to construct temporary shelters.

Meanwhile everyone else continued to suffer an interminable wait on board the Mayflower. Only one person had died during the crossing, under mysterious circumstances – perhaps related to the enmity between the Saints and Strangers. And one child was born – the son of two of our ancestors, Stephen and Elizabeth Hopkins. They named him Oceanus. And it is significant to note that during this agonising wait in such inhumane conditions Elizabeth managed to stay strong enough to care for the sick and dying, while at the same time nursing her baby boy. And while they waited yet another baby was born, and another death occurred. Dorothy Bradford, the young wife of William Bradford – one of the Saints leaders and one of the men out scouting – either fell over board, or jumped in desperation, or may even have been pushed – such was the madness on board. What actually happened to her has never been discovered. And young Bradford, whose detailed diaries chronicled both the voyage and the establishment of the colony and who became the colonies second governor, refused to ever speak about it.

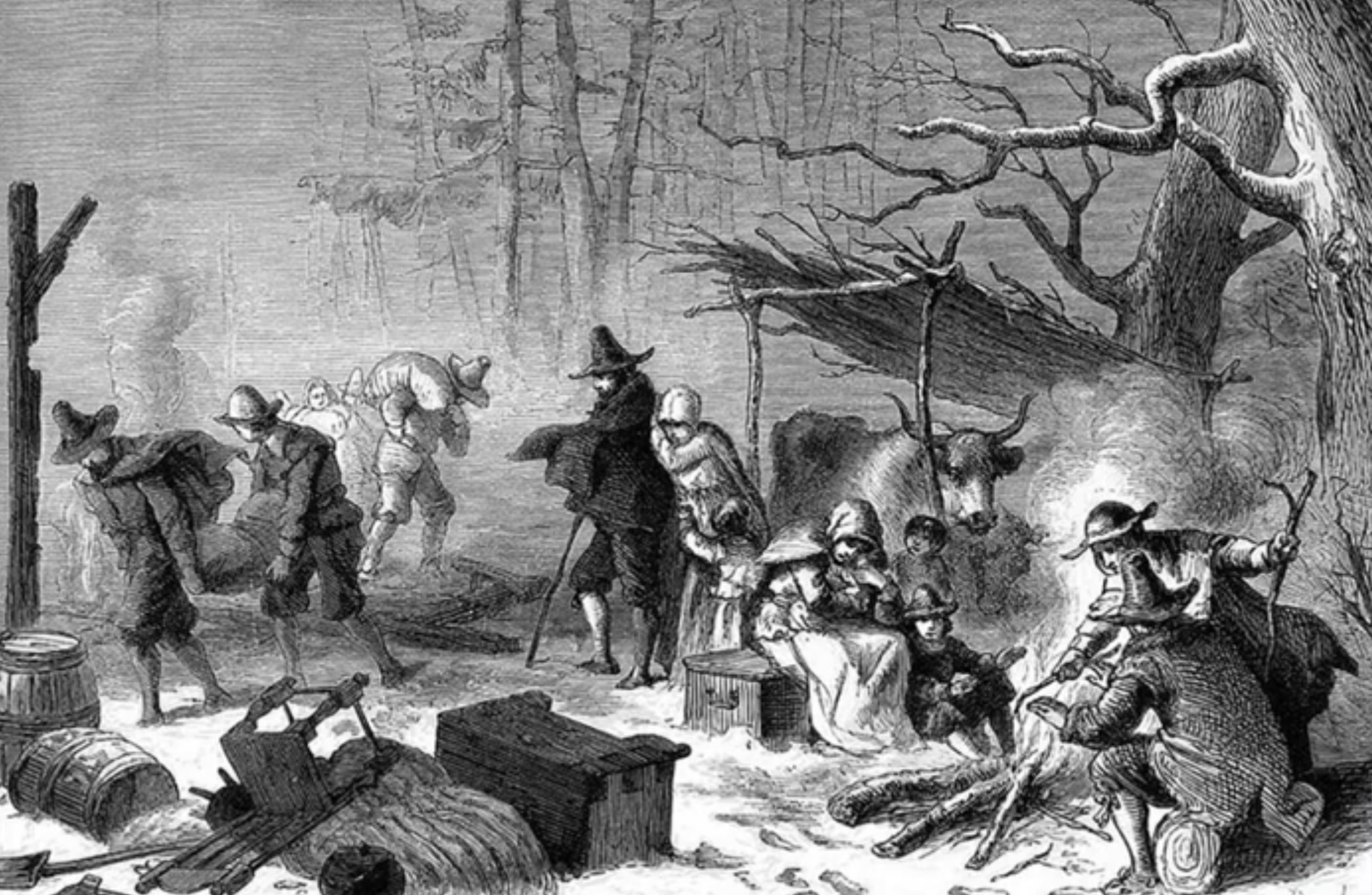

By the time the scouts returned to take the ship across the bay to the spot that would become Plymouth Colony, it was already well into December, the ground was frozen, most everyone was sick, some had already died, and few were in any condition to build shelters, or find food. And so of the 102 passengers who were alive when they first arrived, only 50 of them would still be come Spring.

Remarkably, among the 12 of our ancestors who made it to the New World, ten of them would not only survive that first horrific winter but would go on to live long and productive lives. One of them was Mary Allerton. Only four years old when she arrived, she would become the longest survivor of the original Mayflower passengers – living to 1699. And all of our ten surviving ancestors, and those of their descendants, related directly to us, remained in Plymouth Colony for the next six generations.

Then in early 1798 Suzanna Perkins (who brings all of the lines of our Mayflower ancestors together) moved to Paris, Maine, where on March 12 she married Phillip Caldwell. Their second child and first daughter Lovina Caldwell would marry Isaac Jennings Cummings (a descendant not only of our Cummings ancestors but also of Mary Towne Easty, perhaps the bravest and most outspoken victim of the Salem Witch Trials). And they would have – among 10 other children – our maternal great great grandfather and Minnesota Methodist minister, Albert Webster Cummings. His daughter Estelle Cummings would then marry Leroy Smith Bishop, descendant of our first Bishop ancestor in the New World who received a land grant from the British Crown to establish a tobacco plantation in Jamestown Virginia in 1638.

This union between Estelle Cummings and Leroy Bishop, while an unhappy one for the two of them, produced our Grandmother Lola who carried and passed on this unique lineage to her daughter, Bernice, her grandson Richard and her three granddaughters, Michelle, Kris and Suzanne. While the names are all long gone, the unique blending of all three of the first successful British colonies in the New World – Jamestown, Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay – lives on in them and their children.

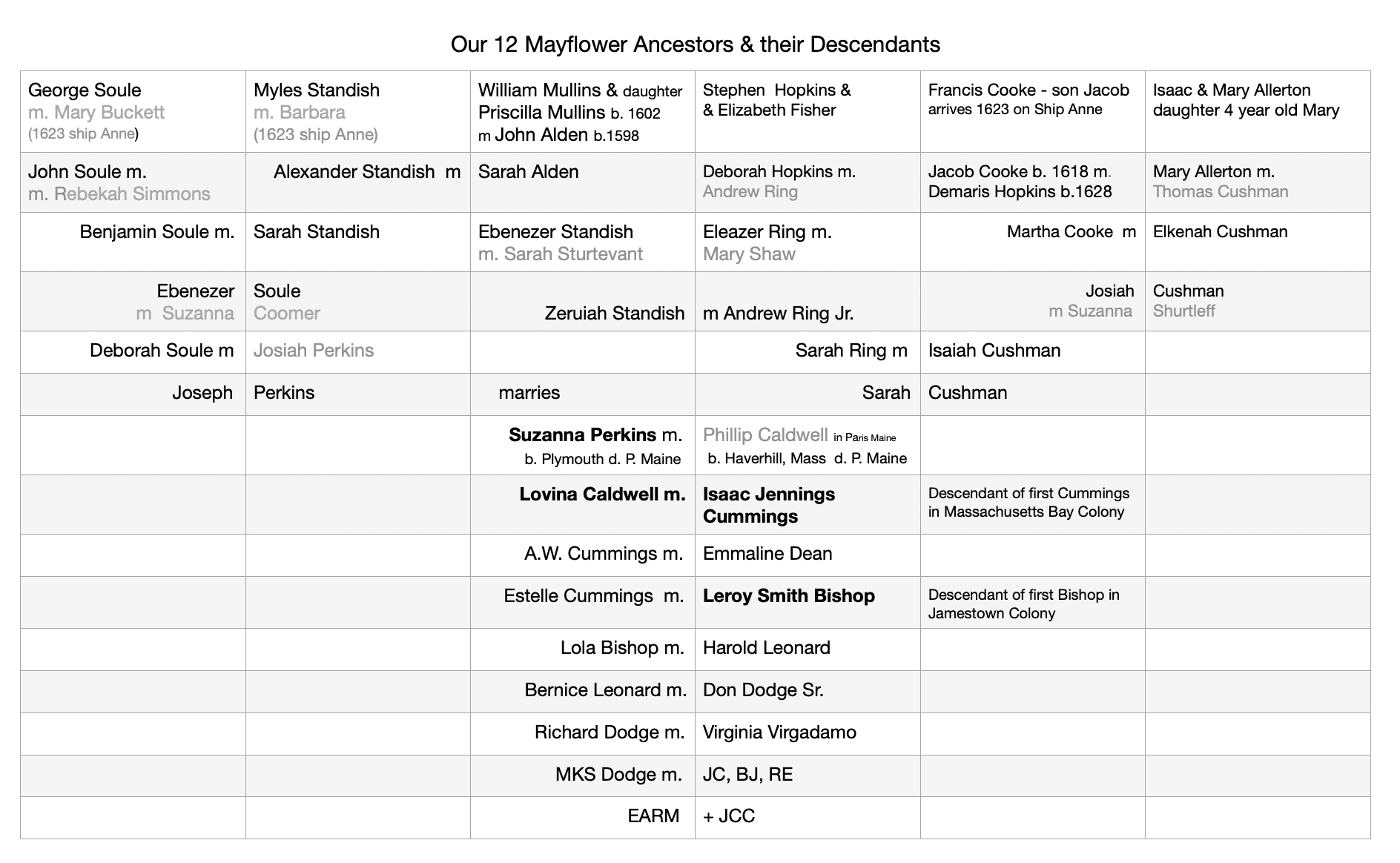

Here below is a chart which demonstrates the coming together of six generations of descendants from our original 12 ancestors. The names in black indicate original passengers or their descendants. Names in grey indicates those who arrived later and married original passengers or their descendants.

It’s interesting to note that Lovina is the first of our Mayflower ancestors to be born outside of Plymouth Colony and her husband Isaac is the first of our Cummings/Towne ancestors to be born outside of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. That both were born in Maine deserves exploration which will come in due time. So will the individual stories of our Mayflower ancestors. But first…

There but for the grace of the Wampanoag Nation did the Pymouth Colony survive.

As proud as we may be of this astonishing lineage it is crucially important to recognise that without the intervention of the local Native American tribe – the Wampanoag – it is quite certain that NONE of the Mayflower passengers would have survived that first winter, let alone gone on to establish the colony, marry, have children and spread their bloodlines far beyond Plymouth.

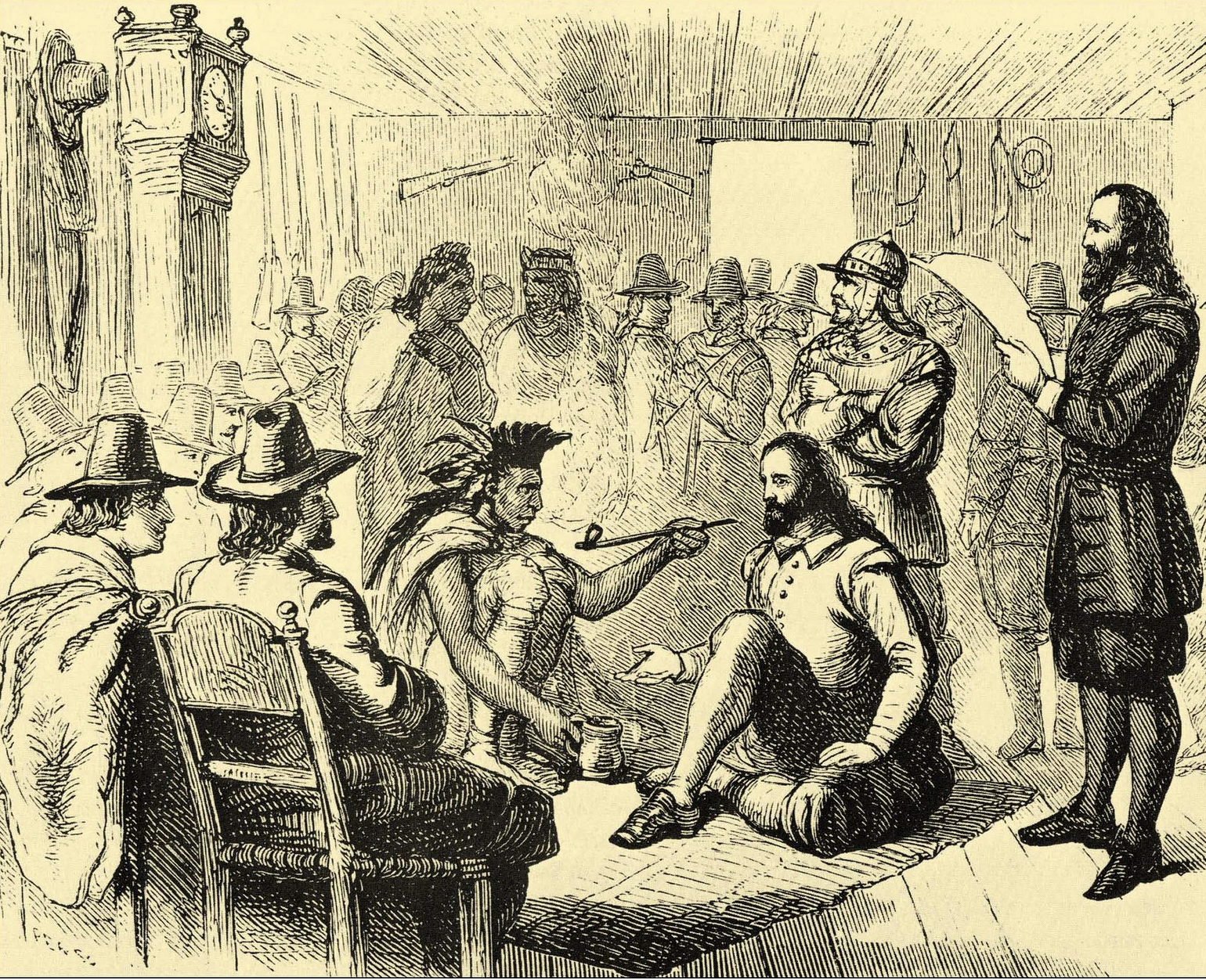

This idealised image of “The First Thanksgiving” bears little if any resemblance to the dynamics between the few survivors of that first winter and the indigenous people who saved them. There was in fact no harvest bountiful enough for celebration for at least three years after the arrival of the colonists. Nonetheless over a period of months a relationship between these pilgrims and the local native tribe developed into a mutually beneficial one.

And this a mutually beneficial alliance is in no small part due to the good sense of our ancestor, Stephen Hopkins, who understood the importance of treating the indigenous peoples with both respect and generosity – something they had rarely experienced in previous encounters with European interlopers. This practical wisdom revealed the stark difference in mind-sets between the Puritan settlers and Hopkins. The Puritans believed that they were God’s chosen and therefore superior in every way to the natives whom they considered to be no more than depraved animals, in need of saving… and presumptuously by them!

But Hopkins, having lived in the Jamestown Colony, ten years earlier, during its early and most unsettled days, had learned well from Captain John Smith, that it was they themselves – the British who were the inferior race in this new land and in great need of the intelligence and skills of the indigenous population. And when contact was finally established it was Hopkins who opened his home to the first Wampanoag chief who entered their village – a gesture that went a long way towards establishing the trust and eventual treaty between the Wampanoag and the colonists that would last for over 50 years, until growing tensions between settlers and native tribes throughout the northern colonies broke out in the devastating year long King Phillips War.

Sadly this intervention from the Wampanoag was – for very good reason – slow in coming. Some years before the Mayflower’s arrival – between 1614 and 1616 – a disease brought by European traders had wiped out almost all of the inhabitants of the ten or so villages that made up the Wampanoag tribal confederacy which occupied what is now Southeastern Massachusetts. Wampanoag means “people of the first light” because they lived on the east coast and so were the first to see the sun rise. They had occupied this area for the previous 12,000 years and had grown to approximately 70,000 people before this disease wiped out 80% of them. The few survivors then congregated in two villages some distance from where the Puritans landed, but were nonetheless well aware of their arrival in late November of 1620. However they purposefully kept their distance until the settlers had dwindled over the winter months to a non-threatening size. Not only did they fear disease, they were wary of these traders habit of kidnapping natives for the European slave trade.

Had the Wampanoag approached sooner many more of the Mayflower passengers would certainly have survived. But the settlers foolishly believed that scaring off the natives with false shows of military might would protect them, so they brought cannons from the ship and placed them in clear sight. They also buried their dead at night thinking the natives would not notice how small and weak they were becoming. But they paid dearly for these pointless strategies. The natives weren’t fooled and patiently waited. And when they were certain that the remaining desperate settlers were no longer a threat, a lone chief of one of the surviving Wampanoag tribes boldly walked into their settlement without a weapon and introduced himself in English. His name was Samoset.

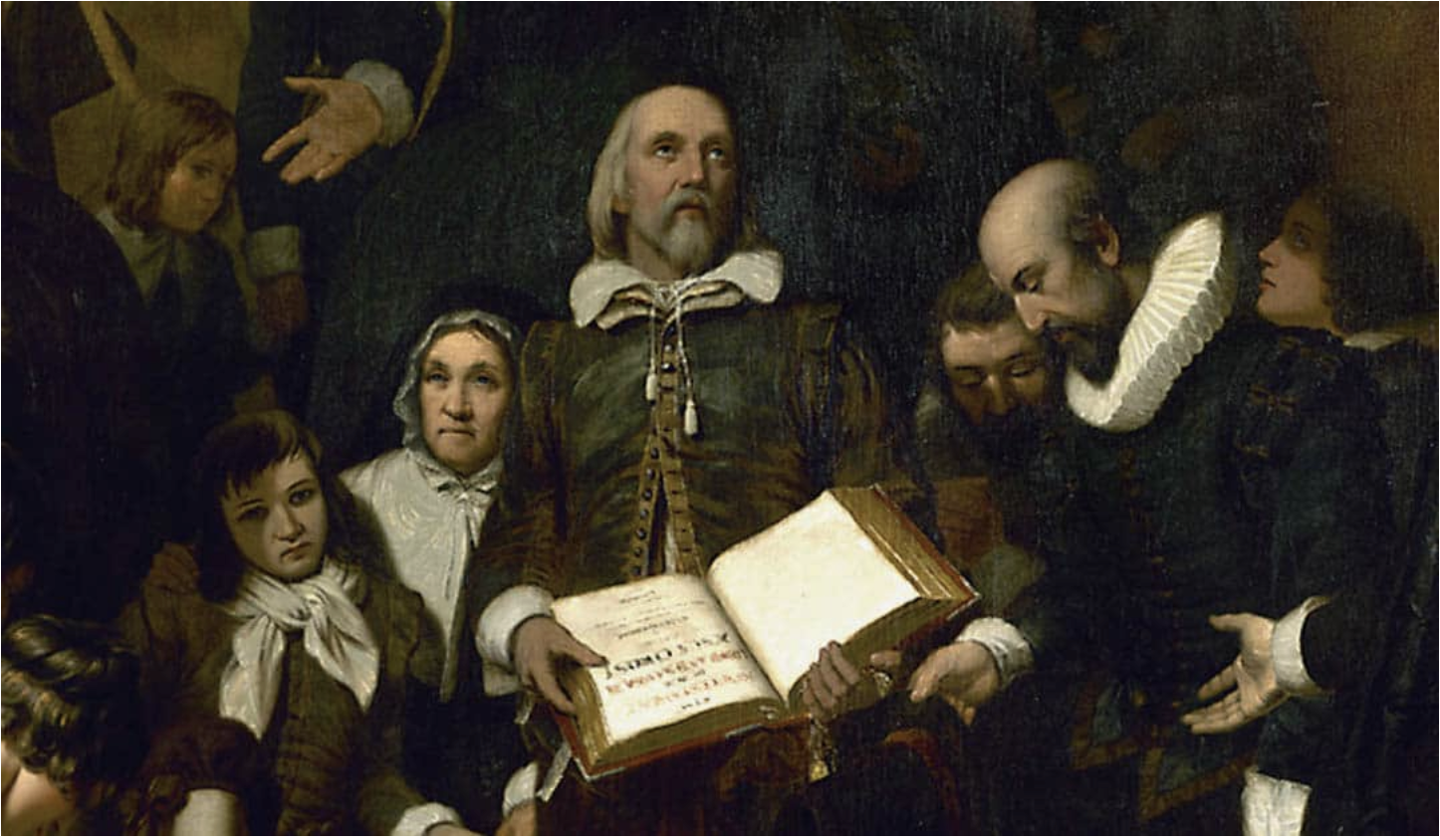

After a few brief interchanges of food and tools Samoset brought Massasoit – the leader of the Wampanoag Confederacy to negotiate his now famous treaty with the settlers. Here he is in the Spring of 2021 with John Carver – the first governor of Plymouth colony – in the modest home of our ancestor Stephen Hopkins.

Samoset also brought a translator whose English was far superior to his own and this man was Tisquantum – later known simply as Squanto because it was easier for the settlers to pronounce.

Squanto’s story is quite incredible. There are several versions of it – but this seems the most accurate as it is the story the descendants of the Wampanoag tell today: In 1614 Captain John Smith was in charge of the British trading ships that traveled up and down the Eastern Coast of America. He instructed the captain of one of these ships – Thomas Hunt – to trade with a Wampanoag tribe – the Patuxet – whose village was later wiped out by disease and which became the location of the Plymouth Colony.

Hunt invited 20 Patuxet braves – including Squanto – to board his ship to conduct the transactions but instead kidnapped them and trafficked them in Malaga, Spain, where Squanto was ransomed to monks who – to his amazing luck – instead of forcing him into hard labour, educated and baptised him. Eventually he made his way to England and finally back to the New World and his native village, only to find that almost everyone in it had perished two years before. He found the few survivors of his Patuxet tribe living with the surviving Wampanoag, and he remained with them until the day he accompanied Massasoit as translator for the treaty negotiations with the settlers.

Massasoit then ordered Squanto to live with the settlers as interpreter, guide and advisor, which he did for the next couple of years, teaching them to hunt and farm. But sadly in his last trading expedition with the settlers, in which he guided them through dangerous shoals, he contracted a fever and died several days later. William Bradford – then governor of the settlers – stayed with Squanto until he died, describing him in his memoirs as a “great loss”.

Now that proper credit has been given to the real heroes of that first winter,

we can at last turn to the stories of our Mayflower ancestors, without any overly inflated pride.

Because their stories are so interrelated I’ve grouped them together as follows:

Captain Myles Standish, John Alden, Priscilla Mullins and George Soule

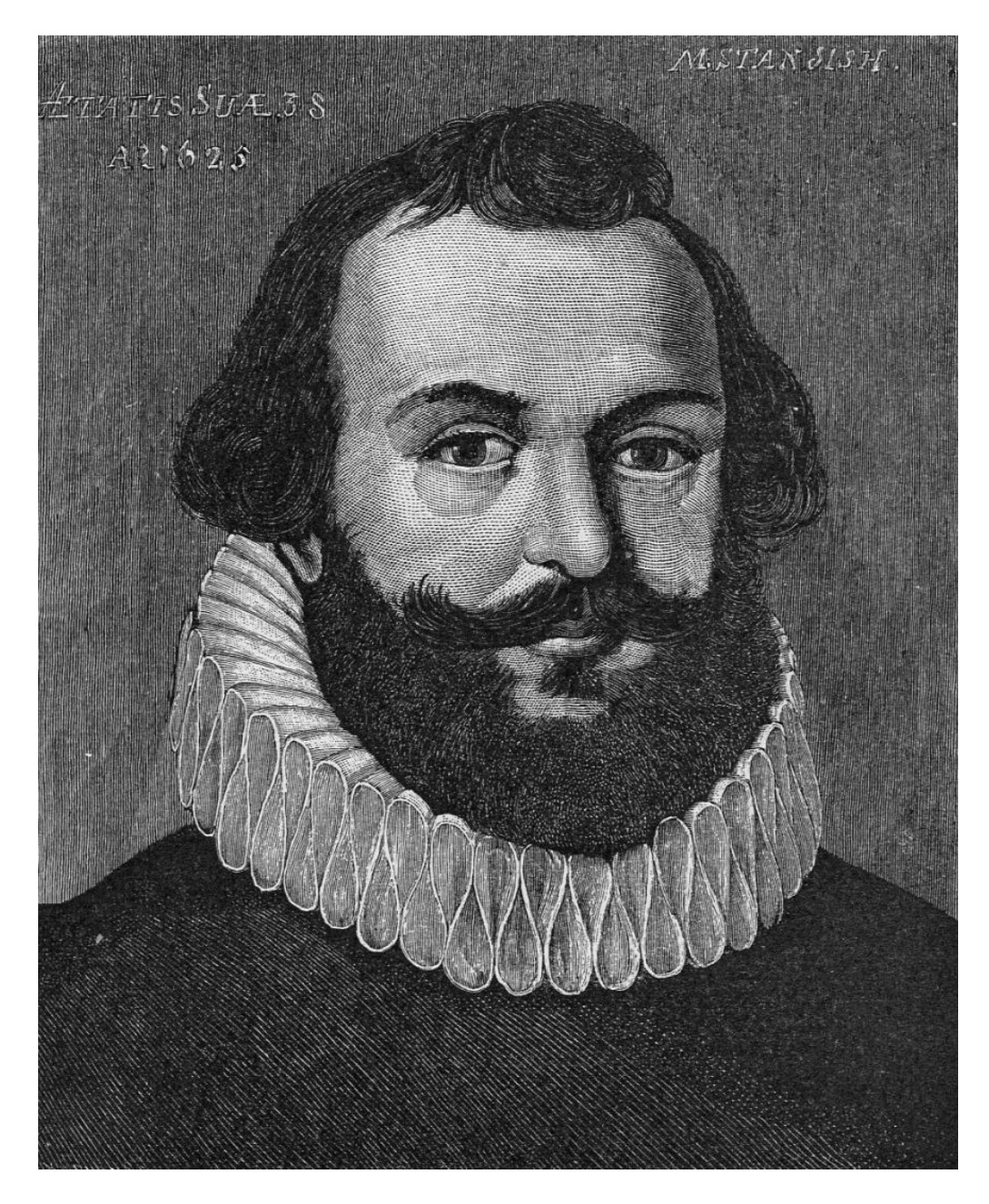

Myles Standish

Myles Standish (ca. 1584 – October 3, 1656) was an English military officer who was hired by the Leiden Pilgrims as a military advisor for their voyage to the New World and then stayed on as a colonist playing a leading role in the administration and defense of Plymouth Colony as its first militia commander – an elected position he held into the 1640’s – after which he acted only in an advisory capacity, turning to farming in Duxbury, Massachusetts until his death at 72. He also served at various times as an agent for the colony on return trips to England, as its assistant governor and treasurer. He was a staunch supporter and defender of the Pilgrim’s colony, but there is no evidence he ever joined their church.

Little is known of his early life or birthplace – only that he was possibly born in Lancashire, England. Nathaniel Morton, secretary of Plymouth Colony wrote the following about him in his New England’s Memorial (1669).

Standish was a gentleman, born in Lancashire, and was heir apparent unto a great estate of lands and livings, surreptitiously detained from him; his great grandfather being a second or younger brother from the house of Standish. In his younger time he went over into the low countries, and was a soldier there, and came acquainted with the church at Leyden, and came over into New England, with such of them as at the first set out for the planting of the plantation of New Plymouth, and bare a deep share of their first difficulties, and was always very faithful to their interest.

We know that he fought for Queen Elizabeth I, who supported the Protestant Dutch Republic against the Spanish but there is debate as to whether he was a commisioned lieutenant or a mercenary soldier. It is only known for certain that he was living with his wife Rose in Leiden and using the title Captain when he was hired by the Puritants as their military adviser. This position was initially offered to Captain John Smith, but his price was too high and the Puritans also feared that his fame and bold character might lead him to become a dictator. So they hired Standish instead, already known to them and whose price was much lower.

Once the Mayflower was anchored off Cape Cod, Standish led two expeditions to find a suitable place for a settlement. Then as many fell ill and died over the next few months – including his wife, Rose – Standish remained strong, caring for the sick and dying. During this time he tended to William Bradford, the colony’s second governor after the death of its first, John Carver. Standish and Bradford became life-long friends, and worked closely together, despite their great differences in character: Bradford was patient and slow to judgment, while Standish was well known for his fiery temper.

During the first and early years of the colony Standish was deeply involved in the protection of both the Colony and the Wampanoag against indigenous tribes hostile to both. Standish’s violent brutality against these tribes was deeply disturbing to Bradford and many of the Puritans, but generally accepted as necessary for their survival.

An astonishingly detailed account of his military accomplishments in protecting the colony during its early years is well worth a read in Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myles_Standish.

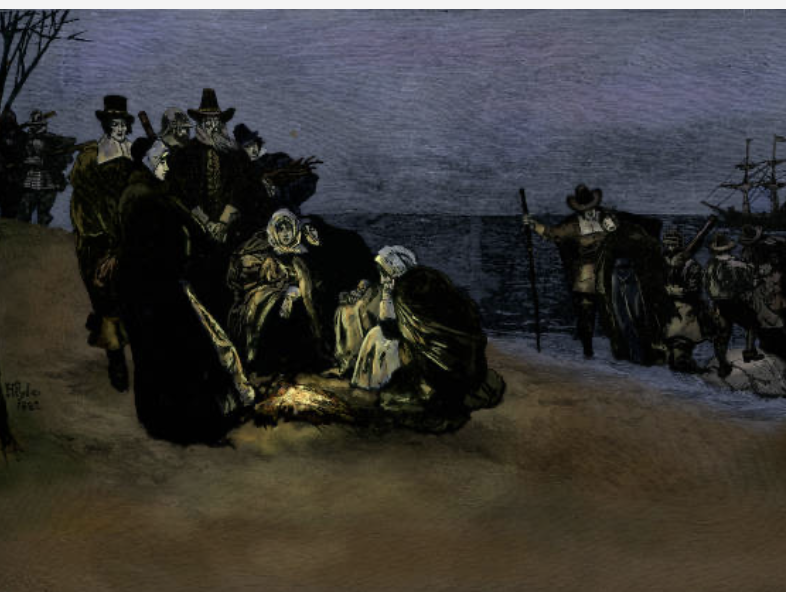

The Embarkation of the Pilgrims, 1843, US Capitol Rotunda. Myles and Rose are prominently depicted in the foreground on the right.

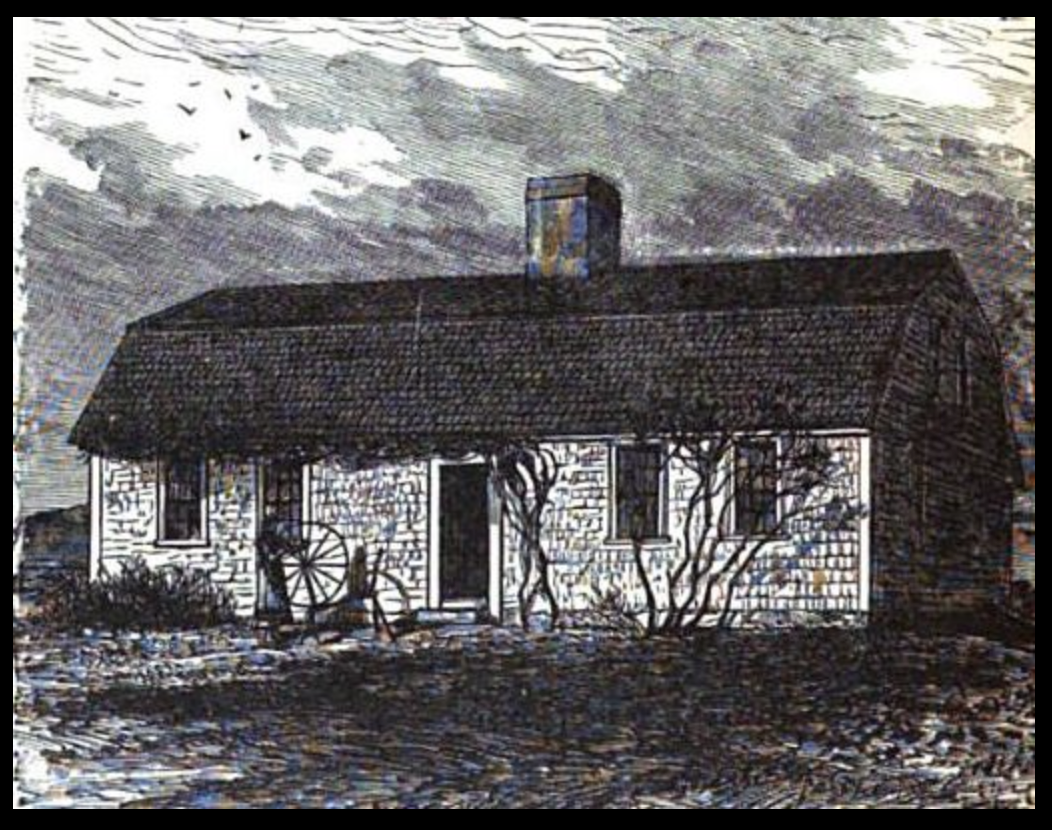

Equally significant were his negotiating talents in paying off the colony’s debts to the Adventurers. His efforts freed the colony from the directives of the Merchant Adventurers, which enabled them to organise a land division in 1627. Large farm lots were parceled out to each family in the colony, with Standish receiving a farm of 120 acres in Duxbury,[ where he built a house and settled in 1628.[

Pictured here is the Alexander Standish House (still standing), purportedly built by Myles’s son on the Captain’s farm in Duxbury, Massachusetts. Alexander would figure in the devastating King Phillips War a half century later when the peaceful relations between Plymouth Colony and the Wampanoag had irrevocably broken down.

The very existence of Alexander Standish leads us to the stories of our next ancestors John Alden and Alice Mullins – a dramatic one that became the stuff of the colony’s most romantic legend. For he will marry their daughter Sarah.

John Alden and Pricilla Mullins

After Myles’s wife Rose died in January of 1621, Standish became infatuated with 16-year-old Pricilla Mullins who’d been left an orphan when her father, William, her brother, Joseph, and step-mother, Alice, all perished that first winter as well.

Myles had taken on John Alden, the Mayflower’s cooper (barrel maker), as his assistant, and being as shy in matters of the heart as he was bold in battle, he asked young John to intercede for him in requesting Alice’s hand in marriage. But unbeknownst to Myle’s Pricilla and John had already developed an affection for one another. Still John dutifully did as Myles asked to the dismay of Pricilla who famously queried John as to why he did not ask for himself. With great pains John relayed Pricilla’s reaction to Myles who did not take the news well. But after some time and a great deal of drama, Myles eventually accepted the inevitable and John and Pricilla married.

Their story is known to literaty history through Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1858 poem The Courtship of Miles Standish. Longfellow was a direct descendant of John and Priscilla, and based his poem on a romanticized version of a family tradition although, until recently, there was little independent historical evidence for the account. The basic story was apparently handed down in the Alden family and published by John and Priscilla’s great-great-grandson, Rev. Timothy Alden in 1814. You can read the entire epic here: The Courtship of Miles Standish.

This following poem is not from Lonfellow’s epic but showed up in one of my many random searches about this love triangle. I cannot find the name of the poet who penned it, but I like it so much that I have included it. That it exists at all demonstrates how much this story has become a part of Plymouth mythology.

Happily for Myles, two years later his disappointment over Pricilla was assuaged with the arrival of Barbara on the ship Anne in 1623, who became his second wife. Among their many children, their son Alexander would one day marry John and Pricilla’s daughter, Sarah. And their daughter Sarah (Myles, John and Pricilla’s granddaughter) would one day marry the grandson of another of our Mayflower ancestors:

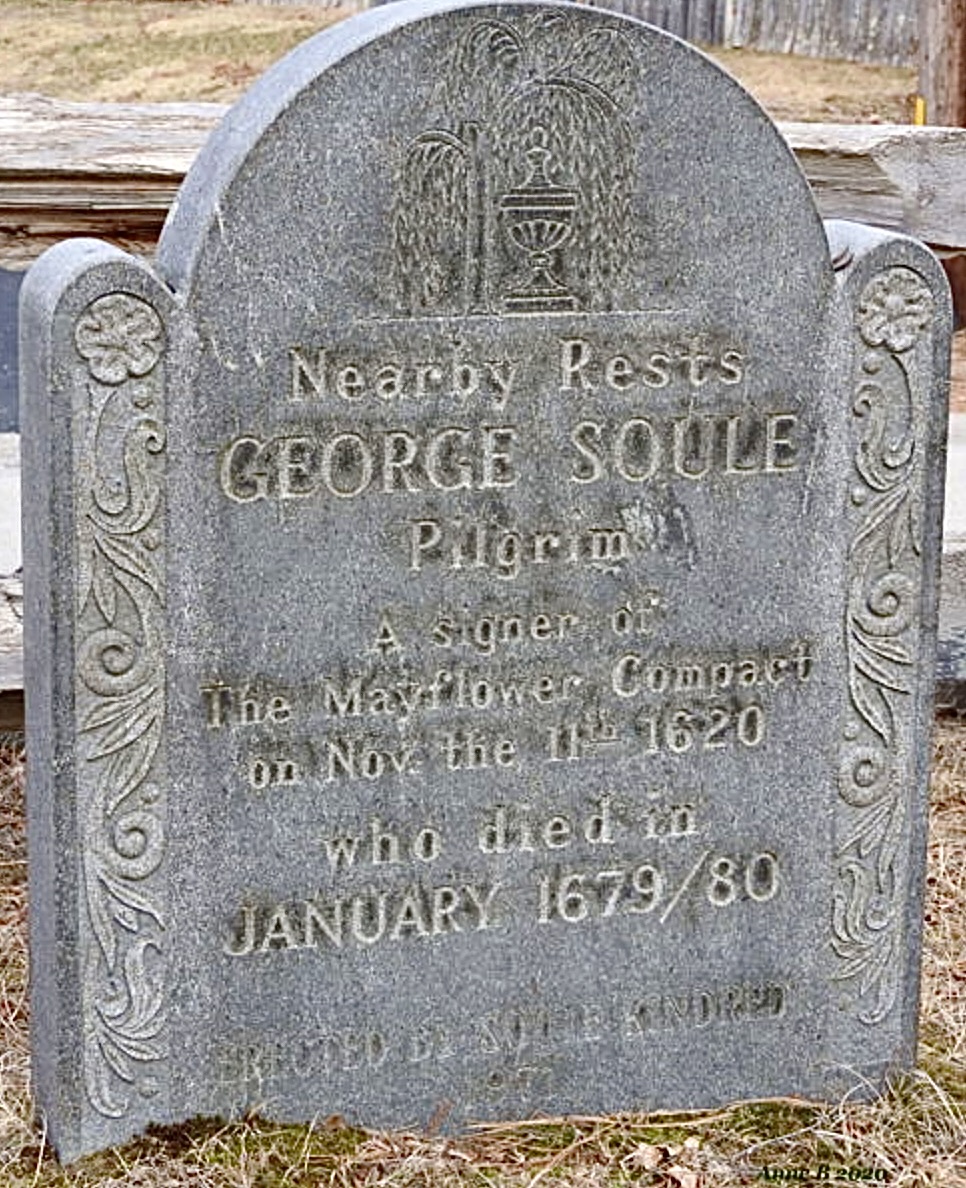

George Soule

George Soule was the manservant of Edward Winslow, one of the Plymouth leaders. Little is known about his roots. But recent DNA research has suggested the following: His parents may have been Jan Sol and Mayken Labis, Protestant refugees in London, England, who fled to Holland where another son Johannes, a printer, died suddenly during the presswork of William Brewster’s “Perth Assembly”. It was this publication that would get the Separatists into such trouble with the Dutch government. And it would appear that all helpers in the press work and distribution of “Perth Assembly” took an oath of silence that was never breached – no matter how high the price. So young George – perhaps now family-less, but a devout member of the Separatist church, was taken in by Winslow, one of Brewster’s supporters, as an indentured servant.

George was one of the 41 signers of the Mayflower Compact and perhaps one of the most modest and humble of our ancestors. Though his future wife, Mary Bucket, would arrive on the same ship Anne in 1623, that brought Barbara to Myles, he was not free to marry her until his servitude to Winslow ended in 1625. In 1627 he was granted land – as were all of the Mayflower passengers – though his low tax bracket indicated that his holdings were not of high value. He had eight children with Mary and lived out his days quietly and productively, serving regularly in the militia, under Myles Standish, whose granddaughter, Sarah, would later marry George’s grandson, Benjamin.

Amusingly Soule was chosen on 20 October 1646 to be on a “committee to draw up an order concerning disorderly drinking and smoking of tobacco.” The law provided strict limitations on where such indiscretions could be practiced and what fines could be levied against lawbreakers. Not amusing then, but to us now, is the irony that another of our ancestors, Stephen Hopkin’s would come to own and run a tavern, leading to several run-ins with the colony’s religious elites for his flagrant disrespect of their rigid moral codes of behaviour. And this takes us to our next set of ancestors:

Stephen Hopkin’s Family, Francis Cooke and Mary Allerton’s Family

Stephen Hopkins

1581-1644

My favourite ancestor has to be Stephen Hopkins for so many reasons. He was not a Puritan, but rather a mercenary who held the distinction of also having served in the Jamestown Colony between 1610 and 1613. And that story needs telling before his involvement with the Mayflower. Hopkins had been hired for a supply mission to the floundering Jamestown Colony. But on route his ship the Sea Venture capsized in a storm just off the island of Bermuda. All on board made it safely to land but the ship was destroyed. The crew fell in love with the island and Stephen decided this would be a super place for he and his family to live. But even the suggestion of staying on the island was considered mutiny so he was sentenced to death. To his good fortune he was well liked by a superior who intervened and saved his life. But he then had to work his butt off to fully demonstrate that he’d been worth saving. He helped build a new ship from the wreckage of the destroyed one and carried on to Jamestown to fulfill his original contract.

But before continuing with his story here’s a fun aside.

Word of the Sea Venture shipwreck in Bermuda got back to England and story has it that Shakespeare based his play The Tempest on their exploits. Moreover the character of Stephano, a drunken and mutinous butler, is said to be based on Stephen Hopkins, a comic character created to highlight human greed and evil. Now while certainly Stephen was greedy for life’s adventures and pleasures there isn’t anything in my research that suggests evil – especially regarding the tireless efforts of both he and his wife during the first horrific winter in Plymouth.

I’ve recently learned of the PBS documentary, Stephano: The True Story of Shakespeare’s Shipwreck, which traces Hopkins’s travels and links him to the character of Stephano. I can only find clips of the documentary, but when I find the full film, I’ll provide the link here.

Back to the Jamestown resupply mission: By the time they arrived the few remaining colonists were hunkered down in a small fort, eating whomever had just died. They had no interest in being re-supplied. They only wanted out of there and the crew of the new Sea Venture, who had no interest in joining their misery, agreed and they set sail back for England. But no sooner had they started off were they stopped by the newly arriving Captain John Smith who ordered them to turn around and head back to the fort. Under his iron fist he turned the motley remains of the original settlers into a hard working force. No work, no food was his motto. So our ancestor Hopkins was kept captive there for another two years. And during this time he witnessed Captain Smith befriend the local native tribe – including Pocahontas. Contrary to myth – this was no romance. She was a young girl, but still she intervened to save Smith’s life when he somehow managed to piss off her father.

Stephen also witnessed the arrival of John Rolfe – who would marry Pocahontas and change the course of Jamestown’s fortunes by bringing the magical coffee seeds he’d smuggled out of the West Indies. The tobacco Jamestown been trying to grow was bitter and unpalatable to the tastes of the British market. But what Rolfe brought was pure gold – not the actual gold they’d hoped to find – but something much better. This success led to our first colonial Bishop ancestor, John, immigrating some 25 years later with a grant from the Crown to establish his own tobacco plantation, Swan’s Bay Plantation, just outside of historic Jamestown.

Returning to our Hopkins ancestor… three years after Stephen had left England he got word that his wife had died and so was given leave to return to care for his children. Back in England Steven married again and he and his new wife had four more children adding to his already three. And then some years later he was given the opportunity to join the Mayflower expedition to what was intended to be Hudson Bay in what was then Northern Virginia. This time he took his whole family which meant that they would experience the horrors of the crossing, the landing in Cape Cod 200 miles north of their intended destination, and endure the starvation and sickness of that first winter.

Stephen’s wife, Elizabeth, was pregnant when they first set off from England in plenty of time for them to be settled in the New World before her expected due date. But because of their delayed departure she was forced to give birth in the middle of the Atlantic during one of the worst storms they went through. Happily, both mother and new baby boy – whom they named Oceanus – survived. Sadly Oceanus and an older sister would die a few years later with one of the diseases that regularly plagued the settlers. But Stephen and Elizabeth would have two more daughters – Deborah and Demaris – both of whose descendants, would lead to the one woman who connects us to all three original British colonies.

Once the Mayflower dropped anchor in Cape Cod Bay, Hopkins – a seasoned sailor and builder became an invaluable contributor to the success of the colony. He was one of the 41 adult men who signed the Mayflower Pact, and was among the first men who Myles Standish led off the Mayflower to survey the land and find a suitable place to build their settlement.

He was also one of the few hearty souls capable of working through the winter to build their shelters, while Elizabeth remained on board, caring for the sick and dying as she nursed her infant son. And as recounted earlier, Stephen was consequential in establishing good relations with the Wampanoag by inviting them into his own home, not only for negotiations, but to eat and sleep – something that would have been unthinkable to the Puritans.

Stephen would go on to hold many positions of authority in the colony over the years, while establishing first a successful farm and then an infamous ale house – which caused him no end of run-ins with his pious Puritan neighbours, who opposed alcohol consumption and even more so the improper conduct that our ancestor, George Soule, was at one time in charge of curtailing

It is great fun, when we consider the literature that continues to be generated about Hopkins, to know that we are descended from him, through two of his daughters, Deborah and Demaris. Deborah’s grandson will marry Myles Standish’s great granddaughter. And Demaris will connect us to our last two Mayflower ancestors – the Cooke family and the Allerton family. And it is to them we now turn.

Francis Cooke

1583 – 1663

Francis Cooke was born in England but traveled to Holland where he married Hester Mahieu at the French Walloon Church in Leiden in 1603. They joined the Separatist Church in 1611 and committed to traveling with them to the New World in 1620. Only Francis and his oldest child 13 year old John made the trip and his wife and other four children followed on the Anne in 1623.

Francis was a wool maker in England and Holland but became a land and road surveyor in Plymouth. He was one of six men named to lay out the boundaries for the twenty-acre land grants to Plymouth’s first settlers. Cooke was also assigned by the court to help resolve financial and land disputes. The Puritans seem to have had a special gift for litigiousness – they were forever suing each other. But otherwise, much like George Soule, he lived a quiet life with little drama.

His son Jacob, who arrived two years after the Mayflower would marry the daughter of Stephen and Elizabeth Hopkins – Demaris – and their daughter, Martha, would marry the son of Mary Allerton – our final and longest living Mayflower ancestor. And their grandson, Isaiah Cushman would marry Sarah Ring, the great great granddaughter of Myles and Barbara Standish, Pricilla and John Alden, and Stephen and Elizabeth Hopkins. And the daughter from that union, Sarah Cushman would marry Joseph Perkins the great great great grandson of both George Soule and Myles Standish – and in so doing tie all of our 12 Mayflower ancestors together. And so we turn at last to our final two Mayflower ancestors, Isaac Allerton and his daughter, Mary.

THE ALLERTONS

Isaac Allerton (ca. 1586-1658) traveled on the Mayflower with his wife Mary Norris and their three children – Bartholomew 7, Remember 5 and Mary 4. Wife Mary gave birth to a stillborn on board the anchored Mayflower on December 22, 1620 and died herself two months later. Bartholomew returned to England with his father in 1627 where he married and had four children – never to return. Remember married in Salem where she also remained, raising seven children.

After Isaac’s wife’s death, he married Fear Brewster, the daughter of Plymouth Elder William Brewster and had two more children – a daughter who died young and a son who would later become a prominent businessman in Connecticut. So of all of Allerton’s children only four-year-old Mary would remain in Plymouth and live out her life there, dying on November 28, 1699, the longest living passenger of the Mayflower.

MARY’S STORY

From the time of the harrowing Mayflower crossing, four-year old Mary would suffer one enormous loss after another. On board the Mayflower, anchored in Cape Cod Bay, her mother would give birth to a stillborn and then die herself, two months later. Two years later her father would marry Fear, the young daughter of William Brewster – the colony’s founder – helping to create for a while at least a sense of family with her siblings and a new baby sister. But from 1927 onward the losses continued. Her brother returned to England and she never saw him again. Her new baby sister died, her sister Remember married and moved away to Salem and soon after her young step-mother died in the 1633 epidemic. All the while her father was mostly absent on supposed colony business in England and throughout the other colonies.

But, as if the good lord decided that this was enough loss for one soul, he had a gift for Mary waiting in the wings. In 1621 a young teenage boy from a prominent Leiden family, had arrive to Plymouth on the Fortune. And fifteen years later Thomas Cushman and 20 year old Mary Allerton would marry. From all accounts they led a happy, prosperous life, never leaving Plymouth, where they raised eight children and then welcomed over 50 grandchildren, many of whom would marry the descendants of our other Mayflower ancestors.

That Mary, who had suffered so much loss, so early in her life was able to carry on so well, may have had much to do with the colony’s strong sense of communal responsibility.

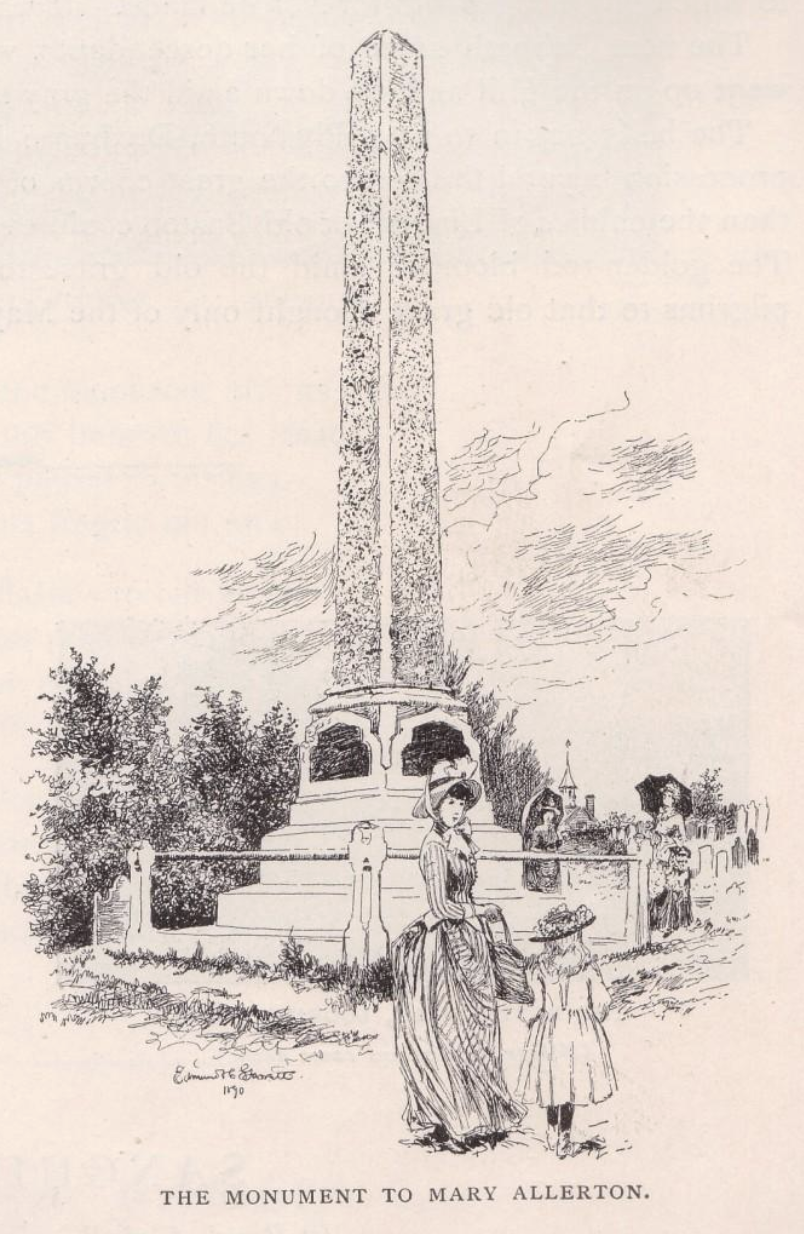

The Cushman/Allerton Monument on Burial Hill in Plymouth, dedicated on September 16, 1858.

From its founding the entire colony – Saints and Strangers alike – adhered to an ethic which ensured that no vulnerable member would ever be abandoned, but always cared for in whatever family most suited the needs of that person – be they a young orphan, a teen in trouble with the law, or a lonely widow or widower.

It was an extraordinary agreement, much like the Mayflower Pack itself, and surely inspired by the colony’s founder and spiritual leader, William Brewster – whom Mary had the good fortune of having as a step-grandfather, especially considering how absent her own father, Isaac Allerton, had been. And there is much more to say about him. But first…

Some reflections on the extraordinary uniqueness of the Plymouth Colony as a whole.

Yes, it was settled by those seeking religious freedom, just as the Massachusetts Bay Colony had been. And yes, it was also populated by those seeking wealth, just as Jamestown had been. But somehow what the Saints and Strangers endured together on Mayflower’s voyage and during that first horrific winter somehow created in all of them an ability to live together in relative harmony for several generations. William Bradford – a devout Puritan and the colony’s governor for many years – was close friends with Myles Standish, the colony’s hot tempered and non-believing military advisor. Likewise, the colony could accommodate the social extremes of Stephen Hopkins and his infamous ale house, and the fervent, if most probably unsuccessful, efforts of Puritan devotee George Soule to reign Stephen in. This remarkable community may have tolerated Myles volatile temper and Stephen’s debauched ways. But they had their limits when it came to the fundamental survival of the colony. And when that was threatened they drew a hard line, and this brings us back to Isaac Allerton, the only known one of our Mayflower ancestors who crossed that line.

ISAAC’S STORY

Isaac Allerton, came to hold several positions of extensive political and financial power in the early days of the colony. He was elected assistant to Governor Bradford in 1621, and continued in that capacity well into the 1630s. He was then sent by Bradford to handle most of the buyout negotiations with the London investors that commenced in 1627, and continued through the early 1630s. But throughout this time – unbeknownst to trusting Bradford – he engaged the colony’s joint-stock company in unauthorised business ventures – for his own person gain – driving the already deeply indebted colony into further debt. This was the line. The colony censured and ousted him. Would that he simply died in poverty and obscurity, but instead he continued his business transactions with neighbouring colonies and ended his days in comfort in New Haven, Connecticut with yet a third wife. For anyone interested in the details of Isaac’s machiavellian exploits, you’ll find a superb account of them here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Allerton

But I cannot end the biographies of our Mayflower ancestors with this jerk – especially when so many of them contributed so much to its very survival and eventual success. I much prefer to end my account with thoughts of Isaac’s daughter, Mary, perhaps walking with her husband and children, like those in this recreation of Plymouth Village below – on a bright sunny day.

I would so love to turn now to Lovina Caldwell Cummings, the woman who connects us to the Mayflower and Plymouth story, and to the kind-hearted son she raised to become our great great grandfather – Methodist minister Albert Webster Cummings. But there is still the final chapter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony for us to face up to – the Salem Witch Trials and the shameful role our first Cummings ancestors played in it. So time to rip off the bandage and get that done and dusted.

Link to MARY EASTY and the SALEM WITCH TRIALS

Your comments are welcome. Please contact me at [email protected]